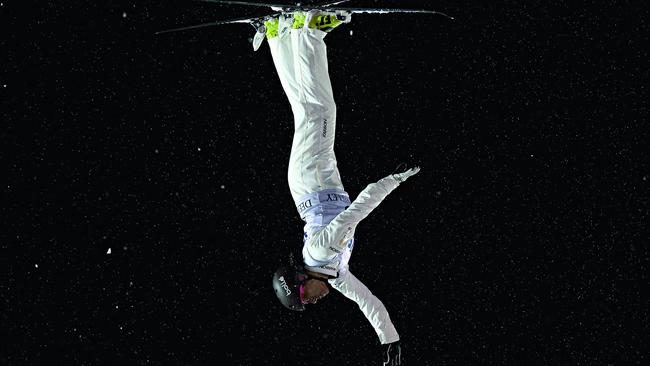

Olympic aerial skier Lydia Lassila prepares for final landing

Her career is a thrilling, horrifying reel of highlights and lowlights. Now Lydia Lassila faces the slipperiest slope of all.

Release your mind to the limitless possibilities of a cloudless sky. Release your body from a snow-packed 65-degree ramp at 70km/h. Release your fears and worldly responsibilities and pressures and commitments in this singular moment of freedom when you hit the ramp at breakneck speed with an almighty swoosh of parallel skis. Release yourself into the exhilaration of floating above this Earth. Up you go. Down you must come. Mentally. Spiritually. Physically. Throw yourself into tucks and somersaults and twists and whatever else you have promised the judges and yourself before the game is decided by the way you finish. In life and in aerial skiing, you must land on your feet. “We have an evolutionary cycle as athletes,” Lydia Lassila says. “We come in. We reach our crescendos. We leave. We are prepared for the first two things. We are not prepared for the third. For myself and for my family, I have to get this right.”

Lydia Lassila is 35 years of age. She’s a mother of two. Her complex six-act play of a career is a thrilling, horrifying reel of highlights and lowlights that will end next February at the Winter Olympics in South Korea. There’s been immense achievement: four Olympics, a gold medal, a bronze medal, a world record, World Cup triumphs. Confirmed status as the most groundbreaking female aerial skier in the world. And now the comeback, as unlikely as it is inspiring. So much so that champion hurdler Sally Pearson credits Lassila’s story, captured in the documentary The Will to Fly, with helping to lift her from “a horrible dark place” to resume training and complete her own remarkable comeback. “Her resilience to get back and get to the top again was truly inspirational,” Pearson says.

The bloke at the surf shop in the Victorian coastal town of Lorne, near where she lives, describes Lassila as well as anyone ever has. “Bloody legend of a chick,” he grins. “I’m tellin’ ya, mate. The chick is a bloody legend.” But that chick has suffered for her art.

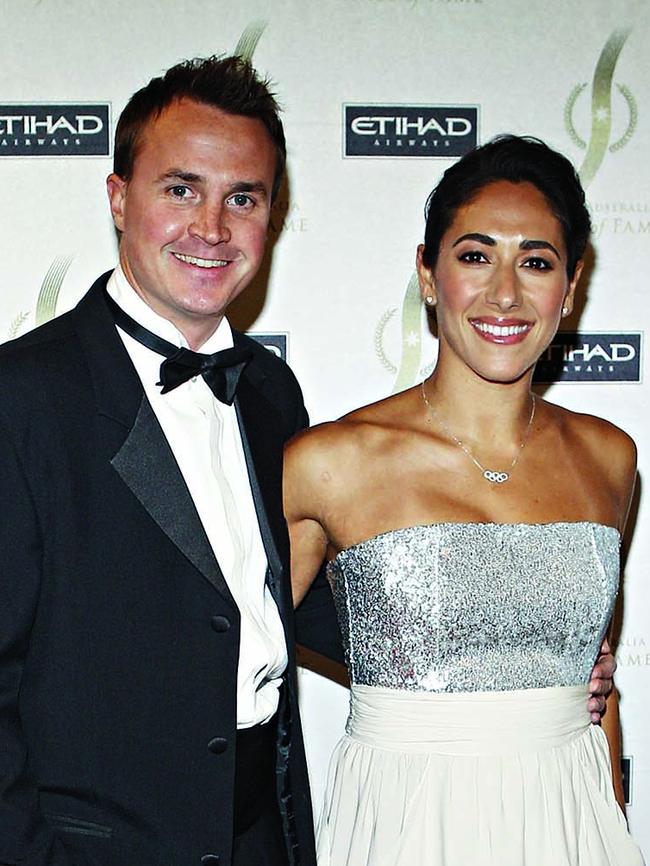

“I actually think what she does is crazy,” says her husband Lauri Lassila, a three-time Winter Olympic mogul skier for Finland. “I know what her sport involves. I would not do it myself. You’re hitting a jump that has a severe steepness. You’re travelling as fast as a motor car. You’re going 15 to 18m in the air. You’re doing three flips and four twists. She doesn’t like it when I talk about this, and understandably so. There is the risk of serious injury or death with this. If something goes terribly wrong, it can happen. It nearly has happened.”

Lydia’s fifth Olympics will be her last and then she will be confronted by the slipperiest slope in modern sport — retirement. The numbness of normal living brings many elite sportspeople undone. So Lydia has a novel approach to her moment of release from competition: six months before the final jump in PyeongChang, she is already letting go. “This is the way I’m going to do it,” she says.

We’re at her house and she’s making sandwiches to take to Lauri at their nearly finished new home in the hills. There’s a bit going on. Her two-year-old son Alek’s milk bottle is in the microwave, she’s making coffees for her father and the Finnish in-laws pottering around, she’s stepping over books and toy trucks and Lego pieces and telling Alek’s brother, five-year-old Kai, that all this mess had better be cleaned up or there will be trouble. She’s grinning. Alek is watching Kung-Fu Panda as if he knows two-year-olds can get away with murder and leave the cleaning to everyone else. Smart Alek.

When Lydia isn’t listening I ask Kai what he thinks about his mother’s sport. He shakes his head and says: “My mum never gets scared. Did you know that?” He pauses and comes in closer and whispers again: “She never gets scared.” He speaks with such an innocent admiration for the woman who brought him into this world that you wish she could have heard it. She’s too busy.

She laughs about the recurring dream she has, the dream that takes her off the ramp and into the endless blue sky for somersaults that never end. “I can’t come down,” she says. “I can’t land. I just keep going around and around doing somersaults forever. It’s kind of beautiful. It’s bizarre. I want to land it but I don’t know how to do it. I wake up and think, not that bloody dream again. It’s your fears that come out in your dreams, right? Maybe it’s about the fear of coming down from what you love doing, not really knowing how to do it. Maybe the dream is about the fear of letting go.”

Act I. Lydia is a promising gymnast. She’s aim ing for the Sydney Olympics but at 16 she has wrist injuries so severe she’s unable to turn a doorknob. Bye-bye gymnastics; bye-bye childhood dream. The Australian Olympic Committee is looking for gymnasts they can turn into aerial skiers. It’s easier to teach a gymnast to snowplough than to teach a skier to do quadruple-twisting triple somersaults. “They approached me and I thought, why not?”

She first tries skiing in July, 1999. “I was an absolute beginner. I couldn’t stand up. They gave us 12 months of instruction, then we have to go upside down. My first jump, I come down flat on my stomach. Pretty funny.” Giggle. “Very funny.” I was an Olympian less than three years later.”

She makes her debut at Salt Lake City in 2002, aged 19, and finishes eighth. “Next time,” she vows, “It will be different.”

Act II. “ This was going to be the one,” she says ofthe 2006 Turin Games. Her rise to the top ranks had been the most rapid in the sport’s history and now she wants to make it count. “You’re in the phase of your career when you’re so hungry for it. You’re desperate. Turin was where I was going to break through. I had all these grand plans but six months before it I caught an edge on the water ramp at training.” Aerial skiers practice their jumps into the water because it breaks the fall. “Second jump, I caught an edge and slammed into the fence. It all happened so fast. My knee exploded. My ACL (anterior cruciate ligament). The pain was ridiculous. I was thinking, no Olympics? That’s it? I felt like my world had ended.”

She agreed to experimental surgery. Allograft surgery; the grafting of a cadaver’s Achilles tendon into her knee. “I was on skis eight weeks later,” she says. “I was a bit of a guinea pig for that surgery, but we were running out of time. I was terrified when I came back. It brought me to tears, you know? It felt good to start with. I went in a World Cup and won it. I was like OK, I’m kind of back to where I was. I wasn’t doing triples, but I was competitive.”

Getting on the plane to Turin was one thing. Getting off it, another. “My knee blew out on the flight. It was shocking. I could hardly walk on it. I knew it was hanging by a thread.” Her first jump was good; she was in second place. One jump to go before the final. “As soon as I landed, bang. The knee went again. The pain was excruciating. I felt the snap but the physical part of it wasn’t the worst. The mental side caused me the most grief. All that effort to get there. All that stress. The whole time I’d been thinking, please don’t let it happen again. Please. And then it happened.”

She clutched at the dead man’s tendon. The high-pitched, panic-filled scream. “It was over,” Lydia says. “That’s what I remember thinking. I’m done. Finished. It was my worst nightmare. I felt like I was grieving. Whether it’s from injury or age, it doesn’t matter how your career ends. It has still ended. We have relationships with our sports as athletes. They’re real relationships. They’re love affairs and when you have to end it, that’s difficult.”

Act III. The 2010 Vancouver Olympics. “A lot of people never come back from a knee reconstruction but it’s not because of the knee,” Lydia says. “They’re scared that it will happen again. I don’t blame them. It’s horrible. But if you’re prepared to accept what might happen in the trade-off for what you might achieve — what do you want more? That’s what I started asking myself. How far am I prepared to go for what I want? That was an empowering question. That gave me so much motivation. I decided I was going all in.”

Lydia moved next door to the Victorian Institute of Sport so she could do three training sessions a day. She engaged a sports psychologist to deal with the monster in her head. When she couldn’t find ice packs that would stay on her bung knee she started a company selling ice packs for all the other people who couldn’t make ice packs stay on their bung knees. The company was called Body Ice. It took off. It basically paid her way to Vancouver, where all anyone wanted to talk to her about was the most horrific moment of her life.

“It was like no one mentioned the crash for four years but because it was another Olympics, it became relevant again,” she says. “The media, in particular, kept bringing it up. How haunted are you, Lydia? Are you over it, Lydia? I actually felt like saying, ‘Can you just shut up about it. Please?’”

The athletes’ village. Two days before the final. She had never seen footage of the crash. “I didn’t want to. Ever,” she says. “An email came through from my management. It was a request that said, can you approve this clip for an Olympic promo? I clicked on it and there it was, a replay of the accident. The one thing I never wanted to see. That was the night I heard the scream for the first time. I’d spent four years trying to avoid it and there it was, playing right in front of me, two days before the final. I was like ‘no, no, no. I am not letting that in.’”

Forty-eight hours later, a jump for Olympic gold. She slid into the fog. “There was this moment where I felt like I was the only person on the mountain,” she says. I couldn’t see anyone.” Go. Release. “I hit the jump and I was good,” she says. “I was upside down and I could see the landing spot on the snow. When I’m in the right state, everything feels slow-motion. It was magic. The landing was great and then I had that oh-my-God moment. You’ve done it. And then the drug kicks in that I’m going to have to give up when I retire. The drug I’ll miss. I’ve never taken a real drug in my life but I’ve felt so high in sporting moments like this. I was full of adrenaline and endorphins. I’d done it. There’s the feeling I have to stop wanting. There’s a chemical interaction between your body and your brain. You love it. You hate it. You get used to it. You live for it. When you don’t have that in your life, you’re going to get withdrawals.”

In her home, there’s a photograph of Lydia in full flight. Arms across her chest as if she is prepared to accept whatever comes next. Family photos. Wedding photos. Photos of her sons. But something is missing in the loved-filled house. That Olympic gold medal. “It’s in a drawer over there somewhere,” she shrugs as if the most prestigious prize in sport is the least important thing she owns. Athletes like this are rare. Achievements are viewed in the context of the personal story behind it.

Act IV. “From my first day in this, I’ve wanted to do the jumps the men were doing. Get out of your comfort zone. Do what is in your heart instead of doing what everyone else thinks you should be doing. I knew the danger of that jump. But I didn’t want to be scared of it.” The quadruple-twisting triple somersault had never been attempted by a woman at an Olympic Games. The tongue-twister became her mission. “The women thought the twad-quisting — sorry! — the quad-twisting triple was impossible for us,” she says. “The men thought the same. I became so driven to prove them wrong. I wanted to do something that had never been done before. I knew it was dangerous. Good! People were trying to talk me out of it. Good! People were telling me to quit while I was ahead.” She had her gold medal. She had Kai, her first born; she was a mother now. Why keep doing it? “People who said those things, they had no idea why I was doing it.”

Pre-Olympic training at Sochi, 2014. “All my competitors were there. It was intense,” she says. “I was the last one to jump. No one knew I was about to do it. I’d only done it on water. I looked at my coach and he said well, now or never. And I thought oh all right, let’s just do it.”

She wanted to go where no woman had gone before. She wanted to vomit. “When you’re at the top of your run and you practise your arm movements, people know what jump you’re doing. They cottoned on pretty fast and I made it and I was really yelling and screaming and punching the air. I was just so pumped. The whole tour was cheering. For them to stop and recognise the moment, that was pretty special. I proved it was possible. I did a trick that no woman has done before. I’d helped the sport progress. That was what I was most proud of. That jump there, that was my Rocky moment.”

Another Olympic final. She could defend her title by ditching the quad-triple and opting for a safer jump on her last run. The dilemma of that moment: professional ambition versus something deeply personal. She could scale it back. She went big. The crouch. One hand in the air, the salute to the gods. Lift-off. Release. She did the turns and twists and everything she had promised herself and the judges. Then she skidded and fell before regaining balance. She had not nailed it. She had not failed it. Either way, she had done it. The degree of difficulty earned her the bronze anyway. Screeching to a halt, she turned and placed her hands on her hips. She faced the mountain and nodded. “That jump meant more to me than winning gold,” she says. “Oh man, it was so close! Playing safe didn’t even come into it. I would not change a thing.”

Aiming high is one thing. Coming down is another. “It was a really tough night,” she says. “I remember curling up and lying in the shower for I don’t know how long. I’m crying so hard. I’m in the foetal position just wailing for ages. I have to let it all go. I’m so tired. I’ve bottled so many emotions. I’ve left Kai behind when I’ve had to, during the year. He’s only two. That’s been hard. Everything just comes flooding back. All the effort. All the stress. All the pressure, all the excitement. All the relief when it’s done. Everything I’ve been keeping a lid on gets washed down that drain.

“But then I’m like, wow, I did it. I tried to do the hardest trick of my life. The trick I have always wanted to do. I’ve done it in the sixth hour of a really hard day of Olympic competition. I’ve done what I promised myself I would do. It’s pure emotion that night. Every emotion. And I know I’ll never, ever do it again.”

ACT V: She vanishes from the competitive scene. She has Alek. She keeps the business thriving. She has more than two years out. And now she can’t ignore the pull any longer. “I’m going to have a crack at being an athlete again,’’ she declares.

ACT VI: The landing. The 2018 Winter Games. Her fifth and final Olympics, the first Australian woman to compete at five Olympics. The last jump of her life. Her novel approach to retirement. “I’m spending this whole year letting go,” she says. “I’m treating it like I’m coming off an addiction. I’m not waiting until it’s forced on me. I’m easing off it now. I’m weaning myself off it. I have my new life set up before I retire. The kids are at school here. My home is here. My life is here. I run my business from here. Walk away at my own pace. You prepare for competition. Why not prepare for retirement?”

On bare-bones training, she has won three World Cup events this season to qualify for her fifth Olympics. No one saw that coming. She’s third on the world leaderboard; fellow Aussie Danielle Scott is eight years younger and placed second. Lydia’s getting better, not worse. “I’m having a year of doing it completely for the enjoyment of it and I’ll see where that gets me,” she says. “I know I’m still competitive. But there’s no more quad-triples. No more stress. My one and only aim is to enjoy the last little stage of my career. I’m rapt in that. I’m not letting go of my sport next year. I’m letting go of it now.”

The recurring dream. The revelatory dream. The beautiful dream in which Lydia hits the ramp with weightless precision. She curls into her first blissful somersault. And then another. And another. Her somersaults never end. “I don’t know how to land it. I don’t know if I want to.” The recurring dream is not scary, it is wondrous. A beautiful dream in which she never has to come down from the high of her sporting career. She knows this is not the reality. An athlete must land on her feet in retirement, she must. Only in a dream can you go somersaulting through a cloudless sky forever.