Inside a secret men’s circle

In the thick of #MeToo, groups of men are venturing into the forest for mateship rituals and “gourmet hugs”. What’s really going on?

Men. Thirty of us circling a dawn fire. Deep forest. You know our kind. Two useless nipples on the chest, a pair of hairy legs and a floppy bald psychopath dangling between them. We made the White Album and World War II. We put the why in X and Y.

“You are a shag on a rock,” says elder Blackburn.

We are shags. We are cold and lost cormorants on the rocky shore of the 21st century. We are afraid to fly.

“Close your eyes,” says elder Blackburn. “Put your arms by your side. Kneel down.”

Change and progress chased us into these woods. One hundred years of under-fathering chased us into these woods. We have run here from our work diaries and our disappointed kids. We have run from our quiet wars and the wives we love and their evolutionarily superior emotional intelligence. We have run from our mobile phones and our beers and our dartboards and our jokes about frisky nuns. We have run from ourselves and into ourselves. Into the past. Into the present. Into the woods.

“Why don’t we all rise up now?” elder Blackburn says. “Feel that bit of strength you have left in your legs?”

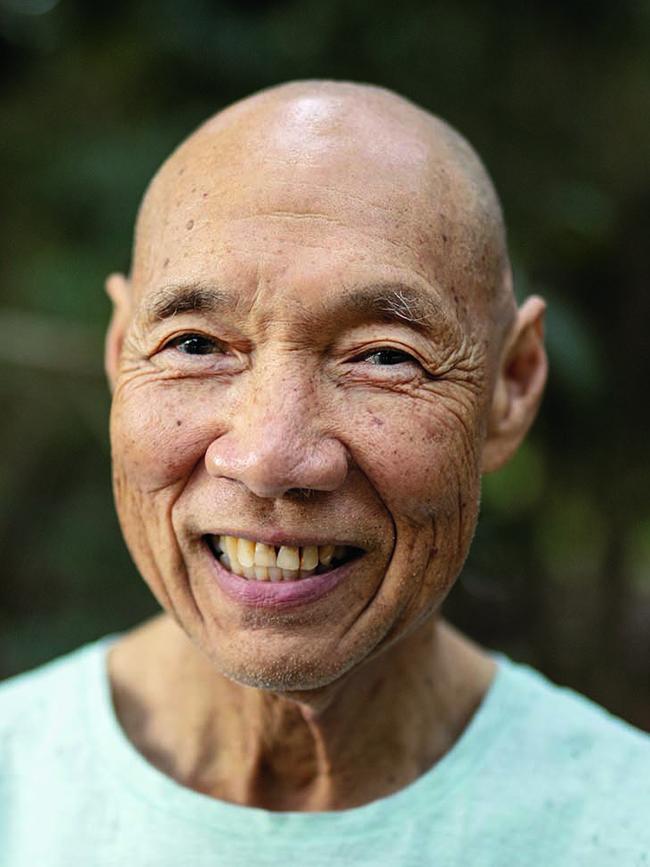

We rise. Thomas, the pharmacist. Justin, the telecommunications manager. Tim, the carpenter. Michael, the businessman. Chris. Aldo. Barry. Phil. Kev. Gav. Pete. Rocky. Rossco. Trev. And Robert Ah Hoon, the 68-year-old psychiatrist and gourmet hugger.

Robert’s the one who let me in. If I made it to the right muster point at the right muster time yesterday, I was welcome to journey to The Rock. The last text I received before my phone went dead around the turn-off to Mount Byron, in the rugged hills of south-east Queensland’s D’Aguilar Range, was from Justin. “The countdown is on, men,” he said. “Patience and gratitude… the journey has already started.”

“Are you men here for Bedrock?” I asked three strangers at the muster point behind the Old Fernvale Bakery on Brisbane Valley Highway. The light in their eyes said they were.

“Now put your arms out,” elder Blackburn says in the dawn circle. “Do you feel your wings?”

Deep in the woods yesterday afternoon — beyond dense clusters of wild forest trees, beyond civilisation, beyond time — I came to an ancient rock, a place where indigenous elders once gathered away from all women. This ancient rock shone like gold in the setting sun. It was as big as a hot air balloon and it leant over onto another rock, providing a shaded gathering place for the 30 men who sat beneath it.

I held my right hand out to Robert Ah Hoon: “Thanks for having me.” He smiled at my extended hand the way an alien who can ride through time might smile at a bicycle. And he gave me a Gourmet Hug. He placed his right hand on my left shoulder. “Put your hand on my shoulder,” he said. He stared into my eyes for a full minute. He gave a knowing half-smile as though he had learnt something new. Then he embraced me for a full minute, breathed deep through his nose. “Breathe,” he said. Our chests heaved as one, rib-to-rib, heart-to-heart. We breathed again and we breathed again and Robert drew back to stare into my eyes for one more full minute. “I see you, Trent,” he said. And I had no response to that.

“Why have you come?” he asked.

Because a colleague told me about these gatherings. They’re happening every weekend across the country. Men in their hundreds, wandering off into the forest to find other men and to find themselves. Man Alive in Fitzroy Falls, NSW. Menergy in Victoria. Amazeing Manhood, Point Walter, WA.

My colleague had a friend who attended an event called Manshine at Camp Somerset, two hours north of Brisbane. It was like Woodstock for modern men: 150 blokes deep in the scrub doing workshops on how to be better men. Blokes going deep. If their wives have problems they call their best friend and go for a coffee and spill their guts over raspberry and white chocolate muffins. If these blokes have problems they bury their mobile phones in their duffle bags and escape to the forest to engage their inner animal and crawl around the grass sniffing other men’s armpits.

“That’s messed up,” a mate said over beers and Friday night football.

“I don’t know,” I shrugged. You know what’s messed up? Twelve dudes on a buck’s night watching a woman shoot ping-pong balls from her backside. Sweaty bear-men stoned on power swapping gropes for roles in shit Ben Affleck films. Big muscle men with “Damage” tattooed across their foreheads strangling their girlfriends. Forty-five Australian men taking their lives each week, three times the suicide rate of women. Six men gone every day. One poor bastard gone every four hours.

“Are you ready to fly?” asks elder Blackburn around the dawn fire circle. “I think we’re ready to leave the rock.”

Robert Ah Hoon waited patiently for my answer as to why I’d journeyed to the ancient rock. I said I had been journalistically exploring the modern Australian man for quite some time. “I keep talking to blokes who say they don’t know where they fit in anymore,” I said. I tried to articulate my feelings and leant heavily on my good ol’-fashioned dot-point man-speak. “You know… work-life balance… #MeToo… world was different for men 10 years ago… world was different 10 minutes ago… Dad’s seven rungs down the ladder of importance, behind Charles and Camilla, the family guinea pigs… you know… ummm… cuz… it’s… like… sorta… hard… for us blokes… to say… you know… in a way that anyone will understand… ummm… what… I guess… we really feel… inside, I mean. You heard any of this before?”

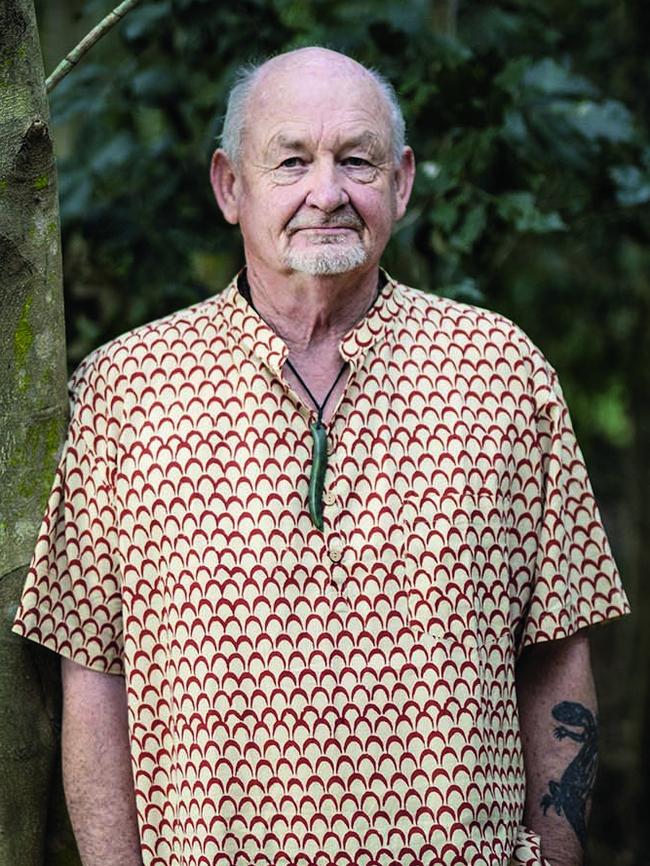

Robert is president of Mens Wellbeing, a non-profit registered charity that’s been hosting gatherings like this as far back as 1991. But never before, Robert said, have the gatherings been so necessary, or so well-attended. This event, “Bedrock”, was limited to just 50 men. It’s for men considering a journey into “eldership”. Elders like our event facilitator, Alan Blackburn, provide a kind of mentoring and selfless service role within the wider Mens Wellbeing community. An elder, as per a kind of mission statement I saw taped to The Rock, is “fully present, visible, approachable, open hearted, engaging, curious; open to receiving guidance from the GUM (Great Unknowable Mystery)”.

Robert read my mind. “You have preconceived ideas about what this is,” he said. Yes. This was all a little screwy. This wasn’t for me. It was for touchy-feely types with good vibes and bad odours.

Most of my preconceptions, flawed and closed-minded as they were, were realised an hour later in a welcome smoking ceremony in which we raised our hands to the Maori gods Ranginui and Papatuanuku, the “sky father” and the “earth mother”. An elder named Rod saw my visible outsider rigidity and wanted to shake it from me. “You need a Pelvic Hug,” he said. “Place your hands at the base of my spine.” He pulled my pelvis to his and we “pelvic hugged”, kneecap-to-kneecap, schlong-to-schlong. I prayed to GUM it would be over quickly and Rod released me with a howl.

“I’ll enjoy watching your journey,” Robert Ah Hoon said. He had only one request. That I jump in, heart and soul. That I push off with my legs and fly away from my rock.

“Now spread your wings,” says elder Blackburn in the dawn fire circle. “Fly!”

And we men flap our wings in the forest. Flap, flap. Flap, flap. Thirty men with their eyes closed, finding their personal mind-sky at the foot of mighty Mount Byron. “Can you see the ocean beneath you?” Blackburn says. And I can. It’s deep blue and wild and dangerous. “We are not the shag anymore,” Blackburn says. “We never wanted to be the shag. We always wanted to be the albatross.”

Elder Blackburn brings the circle together once more. He’s a Kiwi sociologist and counsellor, a former chief executive of Man Alive, the first social service in Australasia aimed solely at men. He’s well into retirement age and now mixes part-time men’s work like this with part-time barbering, a lifelong love. He can fix a man’s hair as well as his head. He’s equal parts Yoda and Dr Phil trapped inside the body of Bill Murray.

That bird exercise was a loosener, he says. Nothing we men can say to each other from here on in could be half as embarrassing as the time we flapped about in the forest like a bunch of albatrosses. “Now there’s just one more getting-to-know-you exercise I’d like to try,” Blackburn adds. “I picked this one up from the forest tribes of Papua New Guinea.”

This curious mateship ritual, Blackburn says, requires men to exchange feelings of connection and trust by gently scratching each other on the base of the scrotum. Terrified faces turn sharply to our elder.

“Gotcha,” he says. “Right, let’s go to work.”

The circle is sacred. No talking over the top ofanyone. A hand raised high means a request for silence. Circle statements from the heart will be closed with a confident, “Ho!” There are no right or wrong answers. There are no answers. There is only GUM.

Session One: Nature. Stroll into the forest. Find my place in the forest. Sit. Silence the “nattering voice” in my mind. Feel the forest for 15 minutes. Return to my sharing partner in the circle.

“What did you experience?” asks Kev, an executive for an engineering firm. I found a burnt log that was good for sitting. Then I felt like a slash and so I relieved myself and sat down on the log and then I closed my eyes and tried to engage with nature and then I smelled an acrid and familiar scent and realised it was my own piss and I wished I had relieved myself a little further away from my focus place and then I kicked myself for listening to the nattering voice in my head because my nattering voice is particularly intrusive and often comes into my mind in the form of Kathy Bates from Misery and she’s holding a sledgehammer in her hands and she’s screaming, “Shut up, Trent, YOUUUU SHUT RIGHT UP NOWWWWW MISTERRRR!”, and I couldn’t shut up so Kathy Bates swung her sledgehammer and snapped my ankles and I opened my eyes to look down at my feet and I wondered about bush ticks and whether or not I should tuck my blue jean bottoms into my black business socks to stop ticks crawling around my ankles.

“But was there at least one moment where everything went silent?” asks Kev.

There was, Kev. I saw a small green spider crawl across my arm and I stared at it long enough that its microcosmic existence came into such sharp focus that everywhere I looked after that moment was magnified by 100. Bugs on leaves, the grand architecture of a spider’s web, the wriggling micro soil landscape the length and breadth of my right shoe sole.

“My job asks me to capture the microscopic details of other people’s lives, Kev,” I explain. “Yet I never stop to capture the small details of my own life.” So I miss my daughter land that perfect hallway grand jeté because I’m checking my Twitter feed to see if some stranger has validated some nonsense I wrote in 280 characters or less.

“What’s up with that?” I ask Kev.

He shrugs. “Slow down,” he says. Kev says he slows down by stripping naked and walking out to his back deck and lying nude for hours in the sun and he doesn’t go back inside until he can hear the song of every bird in his neighbourhood. Kev has found his GUM, the great unknowable mystery that he connects to weekly through every gifted warm sun ray that reaches his bare white backside. “Ho!”

Session One-and-Three-Quarters: The Swapple. Find a man you sense some connection with. Lean over and nestle your head into his shoulder; allow him to nestle into you. Transfer your weights, support each other, then wrap your arms around each other’s back. Now gently slap your partner’s back with a languid, rolling arm motion. The Swapple Hug.

“We are illuminated souls,” says elder Blackburn. “The illuminated soul is dropping your ego and moving toward your true self. You drop all that ego shit. You are open to everything, without ego.”

Session Two: Ease and Grace. Split into groups of four. Discuss with your group a moment when you lived with ease and grace. The men in this circle can rattle off with great ease the many times they’ve been graceless. Acts of rage and recklessness. Bad marriage bust-ups and booze; swan dives down the black hole of depression. Crisis so often drives men into these woods. Disillusionment. Displacement.

“Men are slower, emotionally,” elder Blackburn says. “Women are faster.” Gracelessness — everything from a careless and hurtful word to an act of violence — is born in the catch-up space between fast and slow. “The woman is whacking into a guy, verbally, and he’s slower, emotionally, and he’s not keeping up, so he hits her,” Blackburn says. “He has an emotional clunk. And he goes through a process of infancy and powerlessness.”

I remember grace. My hand on my dead father’s chest, telling him I love him, thanking him for all those moments he was graceful and understanding all those times he wasn’t.

Thomas, the pharmacist, remembers his dad, too. “He passed away 10 years ago,” he says. “He worked hard. A very responsible man. He was old school, didn’t show any emotion. He couldn’t show love. He never learnt that. He worked very hard and didn’t have any time with us. He was stressed quite often.”

Thomas was just like his dad in his 20s. He puts a hand on his heart. “I was building this pie in the sky but I wasn’t fulfilled in here,” he says. He’s a father of two kids now. He works in the oncology unit of Brisbane’s Mater Hospital. “I like to be reminded that I will die,” he says. “It helps me live my life fully. My patients always say, ‘Spend as much time as you can with family’. Do your work the best you can but work won’t remember you. ‘Who was Thomas?’ ”

Thomas recently cut back his work days. Less pay, more life. Every Friday morning he sits on a bench in Brisbane’s bustling West End. “I’ve been doing it for a year and a half now,” he says. “I just sit there and I wait for people to come by and talk to me.” He simply listens. He puts the stories of strangers on a pedestal. He doesn’t guide their stories. “That’s ease and grace,” he says.

Stewart is hard and soft. Hard in muscle, hard on himself. He remembers his job as an orderly in an aged care home. A 106-year-old resident wanted just one more nip of scotch before she died. “Just one, Stew,” she said, every afternoon. “Just one. Just one. Just one.” She hadn’t tasted scotch in so long and staff weren’t supposed to do what Stew did but one day he caved and he poured two clandestine nips into two glasses and he shared a quick and quiet drink with that dear old woman and he wished he could have frozen that still afternoon in time and the old lady could have sipped that quality scotch forever and not have to die like she did days later. Stew cries in his seat. “I was graceful that day,” he says.

Thoughts from a zipped-up swag on a starry, starry night. All this activity; all this embarrassing, egoless heart and soul work in the time of #MeToo. Blokes — thousands of them — in forests across Australia crying, laughing, role-playing, transforming, talking their ears off in a quest to become better men, better husbands, better dads. No blame. Just ownership. Own ya shit. So what’s the catch? When’s someone gonna sell me something? A religion to save my sorry soul. A new-age book to fill my life shelf.

“I felt the same my first time,” says telco manager Justin. “I rocked up and I saw a whole bunch of blokes hugging each other and I was pretty homophobic about all that and I was like, ‘What the f..k is all this?’ It was confronting. That was all part of my hang-ups. I kept saying, ‘What’s the catch?’ But no one was trying to sell me shit. It’s just blokes who want to talk about stuff.”

Three full days of it. Breaks for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Men talking about men over beef stew, bacon-and-egg rolls and chicken curry.

“I feel alive,” says Rob Grimes, another elder. “It’s a time that I can be real and I can connect with other men deeply.”

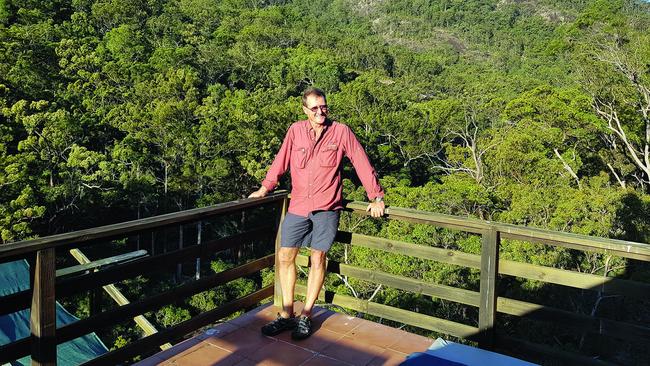

Tim Easton, a Bedrock regular, is 57 years old and feels like he only started to know who he really was as a man in his late 40s. He carried baggage into a marriage long ago. “When I was 13 I actually witnessed my sister falling off a cliff in Lamington National Park,” he says. “I hadn’t really dealt with that as a start. My marriage ended and I was like, ‘Who the f..k am I?’”

Tim recently dived into an “honouring” process. He wrote to his beloved kids and conveyed the depths of his gratitude to them. He then wrote to his ex-wife. No anger in the letter. Just grace, honouring the love they’d lost. “It took me so long to write that,” he says. “We’d been in love. We had some utterly beautiful times together. I’d known her since I was 17. I poured my heart into it.”

He got a two-word email response: “Thank you.”

“Ha!” he laughs, shrugging his shoulders. “She’s like my father, ‘We don’t do emotion’. But she meant that ‘thank you’.”

Rob Grimes wants me to try something. Go to the bathroom when nobody is around. Find a mirror. Find yourself. Look deep into your own eyes and say these words: “I love you, Trent.”

“You say it 50 times,” Rob says. “After a while it’s not even you talking anymore. It’s a higher self, looking into your own soul.”

I love you, Trent. I love you, Trent. I love you, Trent… Rob smiles, raises his eyebrows, nodding. Justin nods knowingly beside him.

“Are you going to step up to eldership tomorrow?” I ask Justin.

“I feel I’m ready,” he says.

Almost a decade ago, Justin was a long way from ready. “I wasn’t present,” says Justin. “I wasn’t being the best father. I certainly wasn’t being the best lover. Or son. Or brother. I thought I was doing OK. I thought I was doing all the things I needed to do. I was working really hard and I would feed and bathe the kids and put the kids to bed and read them stories.”

Then his wife went off with another bloke. “Because I just wasn’t present.” He sighs, shakes his head. I extend my right hand to Justin for shaking. I do it without thinking. The last two times I did this to him he scoffed at my hand and embraced me in a firm hug.

“You keep throwing that hand at me?” he says.

“Sorry, I can’t help it,” I say.

“Why do you do that, man? What’s with that?”

It’s in my DNA. Greece, 5th century. Blokes shook hands as a sign of peace, to show each other they weren’t carrying weapons. One of my old man’s three key messages, alongside “Don’t do smack” and “Wash under the foreskin”: “You meet a bloke, Trent, you shake his bloody hand.”

“What we were trained to do as kids is what we always do,” Justin says. There are good and bad sides to that. Learnt behaviour, says elder Blackburn, is the root reason most men are here.

“Where are we at in 2018?” I ask elder Blackburn over a black tea beside The Rock.

“Who?” he asks.

“Men.”

“Oh, that’s a big question.” He breathes deep and gives a 100-year history of man problems. “My generation, the baby boomers, all the men in our world — our fathers, our uncles, our football coaches, our male teachers — were all ex-war,” he says. “Their fathers were all ex-war, too. We had a whole generation of fathers up to about 1949 who had been traumatised, thousands of them. And we were the recipients of that. They didn’t know how to father us and we were all under-fathered. And over-mothered, by and large.

“So then you start having more fathers who are under-fathered. We’re educated on a lot of things, baby boomer men, but we don’t have emotional intelligence because we’re all under-fathered.

“Then feminism came along. It was absolutely necessary and there was no negotiation. Men went along with it because they had to. It didn’t mean it changed your view of women. It meant you kept your mouth shut. We never dealt with the underlying notion of ownership of women. We hadn’t negotiated our own shit. We were bystanders in the process and we didn’t actually sit down and say, ‘How are we going to be in relation to this new world?’ So when the #MeToo movement comes along, by and large, men are bewildered.”

Some, he says, lost their sense of place. Place, he says, is tied to sense of self. He taps my shoulder twice. “Here’s something for you,” he says. Something to remember with my two daughters. He whispers it. “A mother gives a girl self-confidence, a father gives a girl self-esteem,” he says. “A mother gives a boy self-esteem, a father gives a boy self-confidence.”

He leans back in his chair, like he’s solved the problems of the world in the time it took for his Twinings English Breakfast to go cold.

“When you see men here,” he says, “what a lot of them are actually looking for is self-esteem, their real place in the world. They’ve got the confidence, but, of course, the confidence is just the wallpaper over this little boy who has no self-esteem. Then you start getting the suicides. You don’t get suicides because they’re overconfident, it’s because they’re lacking in self-esteem. There is something here that gives these men a sense of place and that gives them a sense of self-esteem.”

A loud drumming echoes across the forest. We must go. “This next session will be the deepest,” elder Blackburn warns, taking big steps down a rock staircase to a path that takes us to the talking circle.

Session Three: Do I Love Myself? Find a partnerto whom you must talk for five straight minutes on that question. Partner only listens. Partner cannot say a word. Then switch.

“I said I didn’t love myself,” I announce to the circle 30 minutes later. “I love 95 per cent of myself but there’s definitely five per cent I hate.”

“Hate’s a strong word,” elder Blackburn says. He suggests I unpack that five per cent.

Usual stuff. Want to build a boat but I can’t. Touch football sidestep not as sharp as it used to be. Often have improper thoughts about Winona Ryder. Still can’t tie a trucker’s hitch. Wrote a book about the time I was raised by drug dealers and people said it was all right and now I feel like a total impostor and maybe that’s tied to some of my own sense of place and why I always feel I’m not worthy to be in any room if I’m not telling some incredible story which is maybe tied to the fact I’m the youngest of four boys raised by a single man who was as manly as they come and maybe this is all why I say way too much in circles like this and why I’m always thinking of narratives in my head when I should be present, present, present for my wife and children. Maybe I just hate that five per cent because it reminds me of the dark wolf that Justin was telling me about over breakfast. All men have a dark wolf and a light wolf inside them and I know I have mine and I need the dark wolf because it can actually get you through the tough stuff — bullies, egomaniacs, Sydney traffic — but you can’t let the dark wolf run wild because that ends with you dancing on tables in your underpants. But what if my dark wolf is just a light wolf who never gets enough sunshine on its naked backside?

“Then this man beside me said something deeply wise,” I say to the circle, pointing at my sharing partner, the man who let me in, Robert Ah Hoon. “Robert said he sometimes thinks back to his 18-year-old self and he remembers how much his 18-year-old self self-hated and how much his 18-year-old self would love the man he’s become at 68. I think back to my nine-year-old self and I love that kid so much and I reckon that nine-year-old kid would love the shit out of me at 39. So why shouldn’t I love myself now as a man because I’ve always been that boy, too?”

The circle is silent. Heads turn to elder Blackburn. A wide smile grows on his face. He nods his head only once, slow and deliberate.

“Welcome,” he says.

Session Four: Eldership. Thirty men circling a fire inside the sacred ceremony hut. Elder Blackburn dabs sacred ash across my forehead. I am stepping up with five other men to be an “elder-in-training”. It’s essentially a vow to give a toss. To listen better. To actively engage with the men in my life who might be struggling. The women, too. I’m gonna be that touchy-feely guy on the phone to some tough-as-nails mate. Why not? What have we all got to lose from this except a couple of digits on that suicide rate; thousands fewer divorces?

I drop a leaf into the fire and that leaf is supposed to be everything that holds us blokes back from being something different, maybe something better. Phwoop. Up in smoke.

And we’re done. Gourmet hugs for everybody. Thirty men saying their farewells.

Elder Blackburn wraps an arm around my shoulder. “I actually got a lot out of this journey,” I tell him. He stares into my eyes. “Mate, your journey’s only just begun,” he says.

We roll up our sleeping bags, pack up our swags and tents. And out we go. Out of the sacred fire circle. Out of all this heartfelt talk. Out of the woods.

It’s only when I’m 10km or so from The Rock, back on the Brisbane Valley Highway heading back to civilisation, that I finally see the GUM. It stops me in my tracks. I rub my weary eyes in case I’m seeing things. I haven’t seen the GUM in three full days in the forest. I see it when I pull into the Freedom service station to fill my car up with petrol. The great unknowable mystery. A complex and miraculous reproductive system, an emotional intelligence fine-tuned over 200,000 years and a noun by which their kind are distinguished. Woman.