Edward Enninful: Meet British Vogue’s first male editor

As Edward Enninful puts it: “I’m black, I’m gay, I’m not rich and I’m not thin.” How on earth did he end up the editor of Vogue?

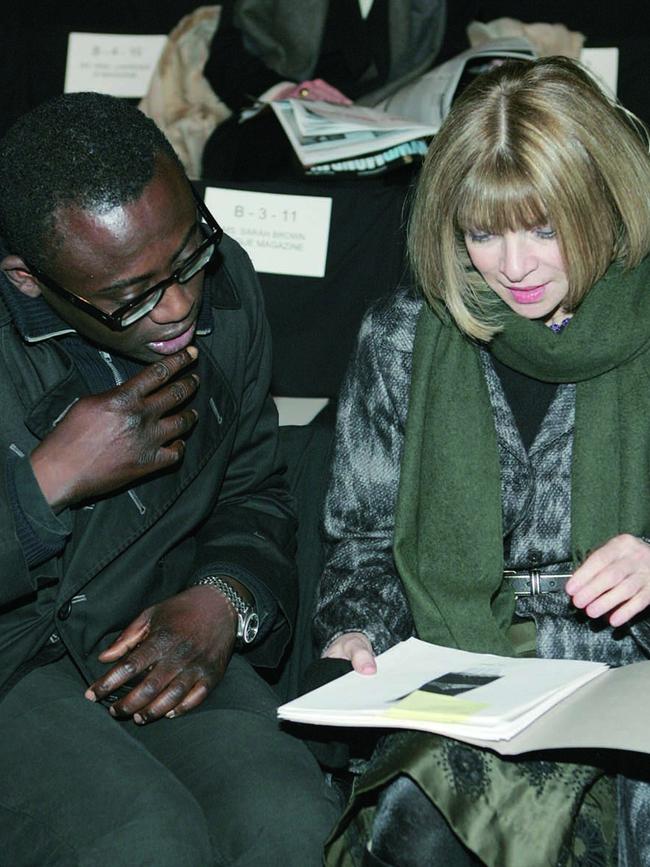

There is a scene in the film The September Issue when a brilliant young stylist goes into Anna Wintour’s New York office to show her his proofs from a shoot. “Where’s the glamour?” she asks him sharply. “It’s Vogue. Let’s lift it.”

Now that stylist, Edward Enninful, is the new editor-in-chief of British Vogue and I’m the one worrying about what to wear to meet him in his office. But he’s determined not to be scary. He has reading glasses rather than sunglasses and speaks softly, with a vast smile. His Boston terrier, Ru, has left a trail of slobber on his immaculate black suit. And he isn’t wearing any socks with his brogues. “No socks?” I ask, pointing to his feet, wondering whether every man should now do the same. “I just like my ankles,” he says, laughing. “And I’ve lost a bit of weight. Thought I might show them off.”

Enninful, 46, wants to be normal but he really isn’t. One of six children brought up in Ladbroke Grove, west London, he was appointed fashion director of British magazine i-D when he was just 18. Kate and Naomi Campbell became his best friends. This once skinny youngster from Ghana, with his mates, helped to invent grunge — the movement that brought an end to the era of glossy supermodels and shoulder pads.

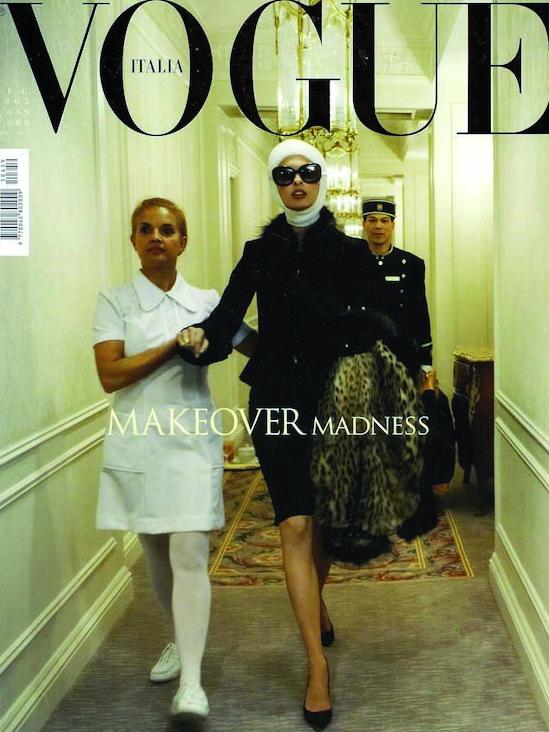

In his 20s, he convinced Vogue Italia to do its first black issue and then a plus-size cover, portrayed Linda Evangelista as a plastic-surgery junkie and covered Naomi Campbell in cake. At W magazine in New York he put Kate Moss on the cover dressed as a nun while shooting ads for Calvin Klein, Versace, Gucci and Dior.

More than 730,000 Instagram followers have seen him messing around with Rihanna, “Madge”, the Prince of Wales, Claire Danes and Michelle Obama. He has no fear. When Donald Trump imposed a travel ban, he posted a video that went viral with celebrity friends proudly pronouncing, “I am an immigrant”. Although he insists he’s not a campaigner: “It just seemed fun.”

When he was announced as the editor of Vogue last year, he was seen by some as an outsider. “It slightly annoyed me [back then] when they called me this party boy: ‘I’m 45 and I’ve been in fashion for nearly 30 years!’ ”

Now he is the first male editor in British Vogue’s 102-year history. “I’m black, I’m gay, I’m not rich and I’m not thin,” he says. “I’m a model of diversity. You couldn’t make me up.” His first issue was a love letter to modern Britain, with Zadie Smith, Salman Rushdie, Twiggy, Cara Delevingne, tea, Yorkshire puddings, corgis, Topshop and Burberry. “Classic rather than class-based,” he says. One of his recent covers showed models from different ethnic backgrounds while they chatted about their sexuality. “Fashion should be inclusive rather than exclusive. Anyone can wear clothes.”

Both Anna Wintour at US Vogue and Enninful’s predecessor, Alexandra Shulman, were scions of famous journalistic families and many staff at Vogue had trust funds and dinky nicknames from boarding school. Enninful’s parents came to west London from Ghana when he was two.

“My mother was a seamstress. She loved clothes. Oh my God, she had peplums and headscarves and frills and colour,” he explains. “People were always coming into our home and she used to pin things all over them. I would sketch for her. My mum would dress them impeccably.”

He was the fifth in the family. “I think I was my mother’s favourite as I was always near her, always wrapping pieces of material around things.” His father was an army officer involved in United Nations peacekeeping operations. “He was the disciplinarian. We lived in Ladbroke Grove but we went to school in south London because my dad didn’t want us to go to school in west London. I had friends, but then I would go home to a different world, different foods, different colours and sometimes a different language. So I felt I lived in two different worlds. That’s been my life, really.

“I was very academic. I did my O-level maths a year early and A-level English literature, politics and sociology. My dad decided I should be a lawyer.”

Then one day he was going to college on the Hammersmith and City tube line in a duffel coat, bobble hat and National Health glasses — “It was quite cool, actually” — when someone started to follow him. “There was a man just staring at me in the carriage. My family were very sheltered; I didn’t have outside friends. By the time we got to my stop I was getting really nervous,” he says. “Then he came up and said, ‘My name is Simon Foxton. I’m a stylist for i-D and Arena and I work with [photographer] Nick Knight. Would you like to be in a shoot?’ ”

His mother was thrilled, his father appalled. “He was like, ‘No. Never.’ I badgered them, but it wasn’t until two weeks later when I was stopped by a modelling agent that my mother convinced my father I should try it. Two weeks after that, a whole new world opened up. I remember doing the shoot and thinking, ‘This is what I want to do. I can’t be a lawyer.’ ”

His father was still very upset. “My mother knew I loved clothes and fashion, and she could see that what I really wanted to do was get behind the camera. I didn’t want to be dressed by someone else. Soon I was model, assistant and cameraman. I was being sent to Paris to do the shows and would then rush back to school.”

When the fashion director of the alternative style bible i-D left, he was given the job. “I had to style the covers and write the features and the shopping pages. I would work until 4am. The ’90s were amazing. We didn’t have any money but we made our own clothes, we blagged our way into clubs. It felt very meritocratic.”

As a child, he says, shielded by his family, he didn’t really know what racism or snobbery was. “In fashion I was best friends with aristocrats and Asians. It was all about diversity and standing out — gay, straight, black, white. No one was in a box. I wanted my stories to connect with society and my covers to stand out but to encapsulate the times.”

He once tweeted, “Racism? Xoxo” at a fashion show when he was the only editor seated in the second rather than the front row. It hasn’t happened since. “I try not to pay attention to racism. I kept my head down and worked. As a model at castings, I felt a bit defeated sometimes, but it’s part of modelling that you are never enough. Other models had weight issues. My parents didn’t raise me to dwell.”

Coming out, he says, wasn’t difficult either. “I was 21, I’d been working so hard in my teens I didn’t have any time for relationships. I wanted my parents to be proud of the career I had chosen. My mother was so pleased when I came out — she just said she loved having a son to go shopping with and talk clothes. She made it sound like the most normal thing in the world.”

Although Vogue is now on Snapchat and he’s a master of Instagram and digital media, Enninful prefers street style to style bloggers. “I like the authenticity of what ordinary people wear to leave the house, to catch a train.” He’s always loved a pencil skirt, he admits, and also a heel and a lot of glamour now. “If I were a woman I would still only wear black and white; I don’t think I’d want to wear anything overtly sexy. I’ve always been a bit prudish about the way I dress. I’m not a peacock. I don’t need to dress up, because I dress other people. For special occasions I wear Alexander McQueen, because he was a great friend. But men should be able to wear skirts; we should wear what we want. People should live their own truth.”

Meghan Markle, he thinks, has interesting style. “She is fantastic for this country. Any young girl seeing her as a princess now knows you can have black skin and still marry a prince — that’s a new development.” Naomi Campbell is another. She is actually on time for him. “She’s the last of the Dietrichs and Garbos.”

He has always been attracted to powerful women. “It’s my weakness or strength — I blame my mother. There was Franca [Sozzani] at Italian Vogue; she let me do anything. And then there was Anna [Wintour]. When you work for Anna, it is not a walk in the park. You have to inspire photographers and designers; it’s about mixing finance and creativity. There is no one on American Vogue just sitting there being fabulous. What I learnt from Anna was to keep going, never sit, never rest on your laurels. Never think, ‘I have done it.’ ”

Everyone in the fashion world (except the British, that is) assumed Enninful would be the next editor of British Vogue — his work was so confident. But he wasn’t taking any chances. For his interview, he presented a mock-up of an entire magazine. The chairman and chief executive of Condé Nast, Jonathan Newhouse, told him over lunch in New York, “ ‘I’ve got something for you to proofread.’ I thought it was a test. But it was the press release saying I had the job. It was a very happy day, although my mother had just passed. It was bittersweet, but she knew I would end up somewhere.”

His father now reads the magazine the day it comes out. “He loves it. But the first time my father realised my career was going somewhere was when he read a profile of me in The Times when I got the editorship. That impressed him. He finally gets that fashion is a calling for me.”

He refuses to say what he thought of Vogue before he edited it. “But I thought, if I edited Vogue, it would speak to all the women I know: rich or poor, young, old, black, white, the prime minister, my neighbour. It couldn’t be elitist. I want to deal with issues such as abortion — serious subjects that women care about. When women at the bus stop say to me now, ‘I can see myself reflected in the magazine,’ that is all I ever wanted.”

There have been rumours that this is only a temporary position and he will take over from Anna Wintour at American Vogue when she retires. “One of my proudest moments was getting the OBE from the Queen,” he says. “At first I thought it was a prank. Anything to do with this country makes me proud. Britain is a small island but it has a big voice and I want it shouting louder. I’m back in my old street. I’m around my family every day again. I love being here, walking my dog through the park, going shopping in M&S — I am not leaving any time soon.”

His only regret is not being able to give his mother a tour of his new office. “My mother was the biggest influence on my life. She was only 65 when she had a stroke and she never stopped making clothes. She taught me to be resilient, move forward, keep walking. That’s what I think now, whether it’s racism, sexism or Brexit. Life for everyone has to get better; the thought it might not is unbearable.

“There is still an astonishing energy in this old country. I get letters from young white women, larger women, black men, gay men. They look at me and see what is possible — you can get to Vogue now by sheer hard work. If I can affect one person, I’ve achieved something.” With that, he is off to change for dinner with the president of Ghana.