Gai Waterhouse: a queen in the sport of kings

She’s risen above the doubters into the ranks of racing royalty. How did Gai Waterhouse do it?

Eggs, soft and scrambled with avocado and sprinkled with parmesan cheese and memories of her dad. She recalls cold winter dawns at Randwick back when 63-year-old Gai Waterhouse was five-year-old Gai Smith wrapped in the warm arms of her legendary trainer father Tommy J. Smith and they were sitting on a cream-coloured pony named Cornflakes riding out to the centre of the track to watch the horses work circles. She’d watch her father watching those horses and every morning she’d come closer to understanding what Tommy was trying to find in all those sprinters and stayers. After enough cold mornings she realised that, more than a horse’s speed and power and rhythm, he was trying to find a horse’s essence. That mysterious element found deep within it that would reveal to Tommy why and how it would be first past the post on any given track; what the horse would need from Tommy in order for it to be the best that it could be. And Gai watched her father watching those horses long enough that she eventually realised the elusive essence could not actually be seen to be found; it had to be felt.

On their way home, Tommy and Gai would cut through Centennial Park and each morning they’d inspect the duck nests fringing the park pond and every morning, without fail, young Gai would somehow manage to find a duck egg that they’d take home and cook for breakfast. Tommy would beam so wide with these miraculous morning discoveries and Gai would laugh with joy because she knew — she felt it deep inside her heart — exactly what Tommy J. Smith needed from her, his only child, to be the best that he could be. She had found her father’s essence.

There’s another part to that duck egg memory — something deeper, something life-changing — but our eggs are going cold and these eggs, prepared by her in-house cook, Fernanda, are the best in the world. “The world,” Gai stresses, loud enough for Fernanda to hear at the kitchen sink of this sprawling top-floor apartment overlooking Balmoral Beach on Sydney’s lower north shore.

Two grand sulphur-crested cockatoos land near a rosemary bush on the apartment balcony, their yellow plumage like some wild hat Gai Waterhouse might slay all those younger, less brave, less original, fashion wannabes with on race day. The Lady Trainer and her plumage, a rainbow of a woman, perched in the stands, binoculars in one hand, hope and 30 years’ hard work in the other, clenched tightly to will another beloved horse — athletes, she calls them — on to victory. Gifted Poet, her first winner in 1992. Te Akau Nick, her first Group 1 winner that same year. Dear mighty Fiorente, Melbourne Cup winner, 2013. (She ran her samurai eyes over that horse on the morning of that hallowed day and uttered just one word: “Wins”.) Dear courageous Pharaoh, the horse with arthritic joints that was called every lame name under the Sydney sun before Gai found his essence and turned him into the champion thoroughbred who won back-to-back Doncasters in ’94 and ’95. That’s her thing, turning the stable roughies — the outliers, the outcasts — into warriors with a mother’s love. And they fight to repay her kindness.

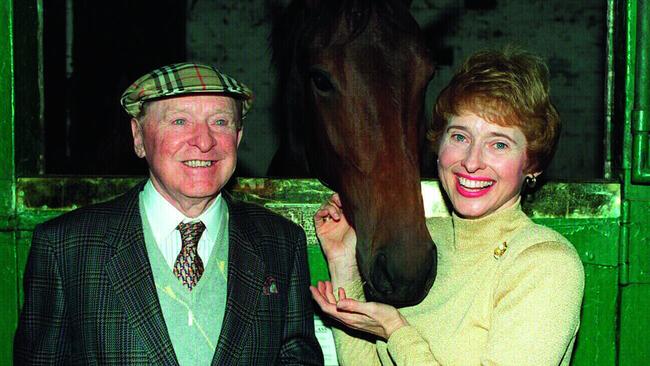

She loved them like family. Grand Armee. Desert War. Dance Hero. All Our Mob. All Gai’s mob. She’s third on the all-time list of winning Group 1 trainers; 136 Group 1 wins and counting. Some 3827 total career wins and counting. More than $245 million in race winnings in this century alone. It’s the kind of record that puts her up there with her old man and not that far behind that other god of racing, Bart Cummings. “She’s better than me,” the great Tommy J. Smith confided to Gai’s bookmaker father-in-law, Bill Waterhouse, not long before Tommy died. But they still underestimate her because surely a woman who looks like a Hitchcock muse could never train so many gutsy winners; all those doubters and knockers and tall-poppy choppers who can’t quite believe a queen could ever conquer the sport of kings.

“Those pests,” she chuckles at the cockatoos. She sprinkles salt over her eggs. “This is black salt from Hawaii,” she says, passing the salt and pepper. “It’s Hawaiian black volcanic salt. Really nice.”

She studies your eyes and your lips in conversation. This comes across as a deep seriousness until you realise it’s more a deep concentration. She’s a good listener who can barely hear. “I lost my hearing about 30 years ago from a fall from a horse,” she says. Communicating is a maddening struggle she buries daily beneath deep wells of grace and deportment-school manners. “I lip-read very well. You make do in life and get through and just make sure you can have a happy life. One of those things I’ve found is that my eyes have been my ears and I can be very intuitive in seeing things, especially with people. It’s body language. It’s quite funny. I’ve had to develop other senses.”

She shifts her head about randomly, left and right. A sense thing. A body language thing, sensing that the journalist sitting across from her is struggling to see properly because blinding morning sunshine is flooding through her balcony doors. “I’m acting as your buffer from the sun,” she says. A genuine Gai Waterhouse eclipse. A man saunters from the main bedroom into the living room in his boxer shorts and a sloppy joe.

“My husband, Rob,” Gai introduces, and a thousand New Idea headlines from the 1980s flood your head like that Balmoral sunshine. The great courtship of Tommy J. Smith’s only child and Bill Waterhouse’s son. The great union of two famous Australian racing families.

TJ’s Girl In Wedding Stakes!

Will Gai follow in Tommy Smith’s footsteps?

Rob takes his seat at the breakfast table. “Show him what you get every morning,” Gai says, with a wry smile. Rob Waterhouse has the voice of a cheerful librarian who deeply values the human right of quiet but doesn’t mind the odd flurry of whispered gossip. He presents his regular breakfast prepared by Fernanda. It’s a fruit and nut face occupying the whole plate — berries for eyes, almonds for eyebrows, a glob of natural yoghurt for a nose and a banana for a smile.

The man adores his wife. He keeps photos of her on his work desk in the living room, despite the fact his desk is directly opposite and within arm’s reach of his wife’s. It’s not at all difficult to visualise a morning when Rob approached Fernanda on the quiet and asked her to create a portrait of his wife out of healthy breakfast choices.

“If I’ve been a good boy, I get that,” he says, his finger tracing the upward curve of the smiling banana. “But if I’ve been very naughty the banana has been turned upside down with a scowl.” Gai drops her head in embarrassment. Rob howls with laughter. “He never gets the upside down banana,” Gai says. Fernanda calls from the kitchen sink: “He’s a very lucky man!” Rob raises his eyebrows in a kind of warning. “If the banana’s scowling,” he says, grimly. “Look out.”

Rob’s gags are always multi-layered. Two or three layers down in the moody banana gag is the fact that this businessman and former bookmaker has a preternatural gift for landing fruit-face-first in the quicksand of controversy that almost always sees Gai pulled in with him. Both Rob and his father Bill were accused of having prior knowledge of the Fine Cotton horse substitution scam of 1984 and “warned off” racecourses around the world, instantly crippling Rob’s bookmaking career. It was possibly the toughest period of their 38-year marriage; a time, Gai says, that would have ended a union built on weaker foundations. “But we flow along,” she says.

“We’re best friends aren’t we?” Rob asks, spooning up the plate’s right eyeball of berries.

“Yeah,” Gai says. “Very much so.”

It’s their empty-nest years but the nest is never empty. Daughter Kate, her league legend husband Luke Ricketson and their two girls share the apartment below. Son Tom, a bookmaker, lives with his wife and two kids just a short walk along Balmoral Beach. “When we became empty-nesters I was delighted to become the most important person in Gai’s life again but I’ve since dropped down to about number eight,” Rob surmises, selflessly placing himself on the importance ladder behind Gai’s beloved King-Charles-spaniel-poodle cross, Bello.

Rob turns his head away with two hacking coughs from a developing cold. “There was no love for Rob this morning because he was coughing and spluttering all night,” Gai says. “I was very cross with him.” But it’s hard to stay cross at a husband who’s busy building you a statue of yourself in the most glorious moment of your working life. The working miniature model for the statue sits on Rob’s desk amid a pile of horse trade papers and notebooks. It’s Gai in her mint green Melbourne Cup 2013 dress, wrapped in a pearl necklace, joyously holding the cup aloft.

“In 100 years’ time all they will know me for is the Melbourne Cup,” she says. They won’t recall every detail of her journey to it. How she started her working life in acting, landing theatre work in London, a stint on Dr Who. “It was December 1977, and I woke up one morning and I thought, ‘No, I want to go back to Mum and Dad, I want to go back to Australia’,” she says. “I closed that acting door and came home.”

Her uncle Dick had passed away and she knew there was an opportunity to come back and work in the family business. “But I don’t think Dad or anyone imagined that I’d work in the business as a trainer. I think they thought I’d come in as a PR girl or something but I used to go in the morning and clock the horses for Dad and watch them. I really enjoyed being in the stables. The more I enjoyed it, the more I wanted to be there. Then it became a bit of a difficult time with my uncle Ernie, who was the stable manager at the time. I think he saw me as a threat whereas all I wanted to do was learn and be part of their team.”

It was the first flash of a theme that would define Gai Waterhouse’s career: the glamorous, intelligent woman having to fight for her place inside a world of not-so-glamorous but fiercely intelligent men. “It was terrible,” she says. “It got terribly sour to the point where we couldn’t stand the sight of each other. It got to the point where if I said it was black, Ernie would say it was white … and Dad, of course, totally supported Ernie because they’d worked together longer and that was his brother. I put in for my trainer’s licence and Ernie erupted.

“I’d driven Dad mad to give me a little stable of 10 boxes and I said, ‘Just let me train out of there, you can do what you like with the rest of the stables’. And that was the final straw in the relationship and Ernie erupted publicly and there was a split. He and his son, Sterling, went off and took out licences and Dad was terribly hurt. He just couldn’t believe this could happen and he saw me as the wedge that caused it. He said, ‘I can’t believe you’ve broken the family up’. And I said, ‘I haven’t, Dad’, and I said, ‘But this has happened and we just have to work through it. I’m here to help’.”

Classic Gai Waterhouse. The eternal optimist. There is nothing — no glass ceiling, no fear, no death of a beloved rock of a father — that can’t be fixed by waking at 2.15am every day, going down to the stables in the freezing pre-dawn and working, working, working toward the winner’s circle.

A filly from the Waterhouse stable recently ran last in a key race, passed the post 20 lengths behind the entire field. “Gosh, she ran well,” Gai said, trackside, to her loyal and gifted co-trainer Adrian Bott. “Her action was great and she really got into things for a while there.” Adrian turned to her and said: “That’s the most positive spin I’ve ever heard, Gai, on the worst run I’ve ever seen!”

Rob’s not sure exactly where the Melbourne Cup statue will eventually stand — “Maybe the Victoria Racing Club can hang hats from it or something”, Gai says — but he hopes those who pass it might consider for a moment the cost of Gai’s success; the hills she had to climb in her muddy black gumboots. “Gai has never had the support of the upper echelons of racing,” Rob says, matter-of-factly. “The major studs, the larger stables, Gai has missed out on [support from] nearly all of those people. It’s a…” — he chooses his words carefully — “surprise to me that she hasn’t had more support from the racing establishment.”

They turn to each other, silently contemplating the underlying reason for this. Gai’s reluctant to say it but Rob isn’t. “I think being a woman,” he says. “And I think it’s also because she generates so much publicity. They’re resentful of it.”

There were times when she felt it was “impossible” to find her place in racing. “It had been really impossible and it has been a lot of times since then, hoping that you might get an owner to give you a horse to train and a lot of times it will go to someone else,” she says. “So it’s constant.”

Rob has another coughing fit and Gai winces but somehow returns with positivity and love. “I’m glad you’re coughing all that up,” she says. Rob nods, finds more momentum in his thoughts. “When Gai got her trainer’s licence there were five other sons or daughters of trainers who got their licence,” he says. “All very prominent. It would be no exaggeration to say you were regarded as the least likely to succeed, and almost as a joke, compared with the others.”

Gai shrugs her shoulders, nods.

“Everyone else had better credentials and, of course, they’ve all fallen by the wayside,” Rob says. “People forget how hard it is training horses. The attrition rate is very high and it’s soul-destroying. Gai is the only one of them — and there were six — who managed to not only survive but thrive.”

And, yet, he says, there remains an influential element of the racing establishment that still refuses to believe Gai has been the chief architect of her own success. “I think it is an extraordinary thing, especially from people who you would think would know better than that. Big names, they sort of don’t see Gai, her record, her strike rate, her great success, it sort of is always…”

“Someone else,” Gai says. “It’s always someone else behind it.”

“They can’t come to terms with Gai looking so glamorous and actually doing the work,” Rob says. “But, of course, Gai’s up before all the other trainers are.” He coughs again; Gai reels back in her seat, less compassionate than last time. “It’s remarkable,” he continues. “The more success you have, people can be resentful. I’m not sure you’ve had much repeat business from many of the Melbourne Cup-winning owners have you, Gai?”

“Oh, a few of them,” she reasons.

Gai’s growing frustrated by the thread of this conversation. “I don’t know,” she continues. “There are always a few loyal people and it’s nice. I love loyalty.” Rob explodes in another coughing fit, the straw breaking the back of Gai’s patience. “Oh, go away cough drop!” she bellows.

It’s the ugliest purse ever made. Mauve-coloured, apple-shaped, the size of a basketball with clasps at the top, resting on Gai’s coffee table. Her fashion sense, she says, was born from her own inherent creativity and femininity. “The actress in me,” she says.

Her beloved dad loved good clothes as much as she did. But he loved them because, as a child beset by poverty and struggle in the NSW Riverina, his family could barely afford shoes let alone a sharp grey wool racing suit. “Where do women get to dress up?” she asks. “We don’t dress up at home anymore. We go around in daggy clothes. The office, you wear the same old thing, maybe even a uniform or… ewwwwwww, black! Where do you dress up? Weddings don’t happen all the time. The one place a woman can dress up and really feel feminine, really have fun as a woman, that’s coming to the races.”

She leans forward on her sofa, opens the oversized pumpkin of a purse on her coffee table. And you realise nothing is quite as it seems with this woman. It’s not a purse at all. It’s a cosy for a teapot containing her beloved ginger morning tea. “Isn’t that a hoot!” she says, slapping her thigh. “A girlfriend from England bought it for me. I thought to myself, ‘That is the ugliest purse I have ever seen in my life — how could she possibly buy me something so ugly?’ Then, of course, she opened it like a clam and there’s this teapot.”

Classic Gai Waterhouse. Assume she’s going one way and she’ll dart the other. You think she’s hard as nails talking about how disciplined she is in the stables — not a haystack, not a horse hair, out of place — then she talks candidly about the crushing loss of her mum, Valerie (she died in 2008, a decade after Tommy) or her nerves on that fateful Melbourne Cup day in 2013, and you think she’s brittle as butterscotch.

“I don’t know if I can go to the races today,” she confessed to Rob over breakfast that Melbourne Cup morning. “What are you talking about?” scoffed Rob. “I can’t let all the little people down,” she said. “What are you talking about?” Rob said.

She was talking about the literal little people, a series of short and kind old men on the gates of Flemington racetrack who had been saying to her all week, “It’s your Cup this year, Gai, it’s your Cup!” She’d been seeing their faces when she tossed and turned in her sleep. She saw, in her busy mind, the disappointment on their faces as she exited Flemington a big-time, well-known, fashionable loser and, make no mistake, the worst part about being a horse trainer is that most mornings you drive to the track thinking you’re heading to a wedding and most nights you drive home having attended a funeral.

“Some of those people like me and some care about me and I couldn’t bear to let them down,” she says. So that’s what she thinks about when she contemplates winning the Holy Grail of Australian racing. Not redemption. Not legacy. Just a series of short old blokes in hats, smiling so wide they might burst.

In one breath over a warm ginger tea she’ll declare the importance of equality for women in the workplace; remind you how her regular nickname, “The First Lady of Racing”, is essentially an insult suggesting her success came by virtue of a ring; then drop a gentle clanger like this: “Look, it’s probably a bit of an old-fashioned idea, but I think women nowadays have a really tough time being happy. I think they so want everything that they forget sometimes you’ve just got to take a deep breath and say, ‘Welllll…’ ”

She shrugs. She believes women have parts of it all in 2018 — love, work and family — and appear “dissatisfied” with the sum of those parts. She’s good with male horse owners because she’s grown up around them, knows what they want and need from her, knows their essence.

She doesn’t employ staff based on gender, only effort. She often hires foreigners on work visas — she struggles to find young Australians willing to work hard for her in the early morning stables because life’s “just a bit too good in Australia”, she says. “It’s unbelievable. Nowhere in the world would you find higher wages, nowhere in the world would you find better working conditions.”

We settle into the sofa, flipping through a series of old photos. A 1975 black and white shot for her acting portfolio where she looks like some knockout cross between Ingrid Bergman and one of Charlie’s Angels. She giggles, embarrassed by the shot. “One of the Indian chaps who works for us saw that shot once,” she says, adopting an Indian accent. “He said, ‘Ohhh, soooo beautiful, so beautiful’. Then he looked from the photograph up to my face and said, ‘What has happened?’ ” She leans back, howling.

Later, Gai has her face up close to an oil paintingon her wall, staring at the image of another girlfriend from England, Her Majesty The Queen. It’s a scene at a racetrack depicted by Australian narrative painter Garry Shead. The work tells the story of the profound period in Gai’s life in 2012 when the Queen sent her a difficult horse to train, “a barrier rogue” named Carlton House. Gai turned the horse from a feisty troublemaker to an impressive placegetter with the help of several people in the painting — renowned horse whisperer Monty Roberts, the Queen herself, the Queen’s racing manager John Warren, Rob, Tom and Kate. She smiles at the way Shead has captured Tom and Kate as joyous, unencumbered kids. She’s reminded how much easier it is training barrier rogue horses than it is raising kids.

She’s thinking about time. She’s thinking about the past you can’t get back. Her dad always told her not to live in it, the past and all its regrets and even its glories. “Life’s very tricky for everyone,” she says. “It’s no easier if you’ve got money. Life’s a battle for everyone. You’ve got to work hard to make sure everything works.

“The track demands a huge amount from you and it’s very important to get the balance. The balance makes life enjoyable. What are they going to put on the tomb? Part of me might hope they’ll say, ‘Gai Waterhouse was the most intuitive trainer’, but they won’t. Really and truly what I hope it would say is, ‘Good woman, an all-rounder, she did have a lot of time for her husband, she did have a lot of time for her family and, just as importantly, had a lot of time for those horses’.”

Everything working in harmony. Family, work, life and you. It was Tommy J. Smith who taught her that, the man in Garry Shead’s painting floating as an angel above the whole track scene, racing hat on his head, eyes fixed firmly down on the great mysterious essence of his life, the girl who always found the duck eggs.

One morning beside the banks of the Centennial Park pond, Gai — by then a little older — discovered the secret behind her uncanny knack of finding all those delicious duck eggs. She accidentally bumped into her dad and an egg cracked in the pocket of his coat. And the truth was even more beautiful than the fantasy. Every single morning, before he thought about the horses or the weather or the track, Tommy J. Smith thought about pocketing an egg from the kitchen fridge for his daughter.

She never found another duck egg after that. She never needed to.