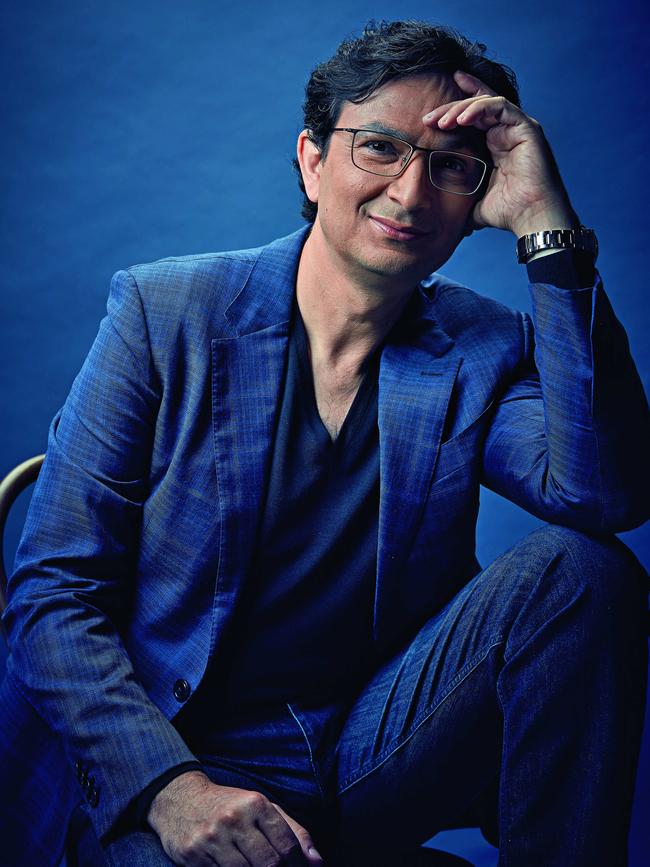

From hell and back: Munjed Al Muderis, orthopaedic surgeon

He paid a people smuggler $2000 to bring him to Australia. Now he’s a maverick surgeon with a $1 million yacht on the harbour.

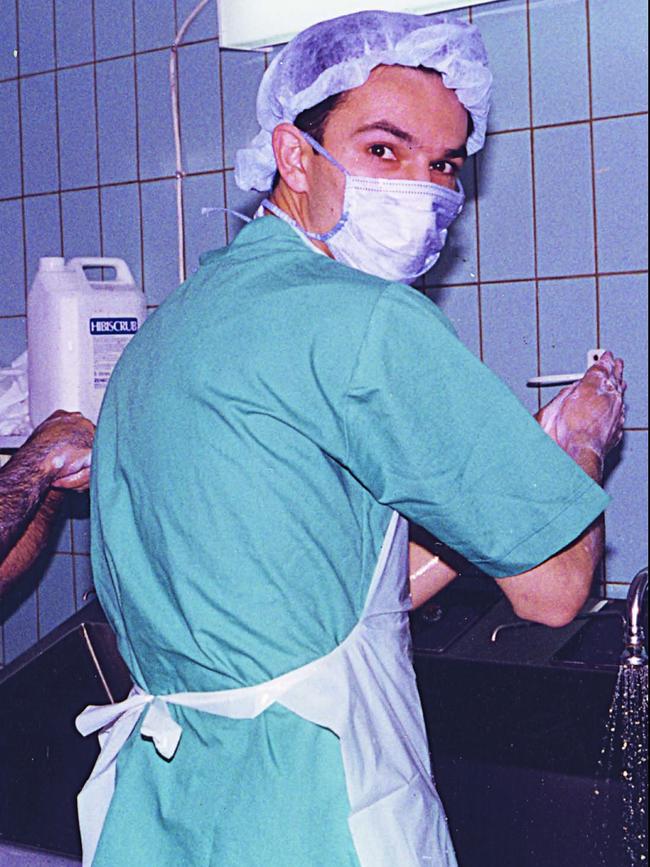

When an orthopaedic surgeon saws through bone, it sounds and smells and looks like hell but that’s not the worst of it. The worst of it, at least from a bystander’s view, is the marrow spray. “Stand back,” a theatre nurse murmurs as power tools wail and the icky stuff flies. Dr Munjed Al Muderis pauses, chattering drill bit raised, and surveys the yawning knee incision before him. Six of the seven people standing in the first-floor operating theatre at Sydney’s Macquarie University Hospital this morning are medicos, unfazed by the gleam of exposed and bloody bone. (The patient’s unconscious. Her name is Susan.) Turning his attention to the seventh, Dr Al Muderis grins: my deep-blue scrubs must nicely complement the green around my gills. Another snarl from the surgical saw. “Next question!” he shouts.

As I will soon learn, anyone seeking a word with the dynamic doctor had better be fleet of foot (and strong of stomach). Up with the sun and rarely home before 10pm, he sets a breakneck pace, fuelled by a daily two-litre bottle of Coke and a nagging sense of time’s finiteness. So many lives to transform; so little time.

Associate Professor Al Muderis, 47, is one of the world’s leading practitioners of osseointegration surgery, a revolutionary procedure that fuses titanium rods with bone to give amputees the ability to walk again. The traditional technique, in which a socket is fitted over a stump, has remained essentially unchanged since pirates wore peg legs. But osseointegration, which the Iraqi-Australian doctor has helped develop, expand and promote worldwide, results in a gait so natural, and a prosthesis so comfortable and effective, that patients wearing long pants can’t be singled out in a crowd.

Al Muderis has performed the life-changing surgery on more than 600 men, women and children in Australia and on another 200 during pro bono visits to his former homeland. Soldiers who have lost legs to improvised explosive devices in Iraq and Afghanistan, accident victims, people with congenital deformities — they behave more like disciples than patients. “He gave me my life back,” says motorbike crash victim Blythe Warland.

Amputees fly in to see Al Muderis from all over the world, and in between attending to multiple Sydney medical practices, lecturing at Notre Dame and Macquarie universities, and traversing the globe training surgical teams and doing humanitarian work, Al Muderis will always make time to see them. Even if it is on the fly. A Brisbane woman recently met with him in an airport lounge ahead of an international flight — “Bring your X-rays,” he told her — and more than one has joined him aboard his luxury yacht for an emergency hardware fix with a side of weekend harbour cruising.

Orthopaedic surgeons have a reputation for being clinical and remote; they practise what amounts to human carpentry, after all. To much of the medical establishment Al Muderis is a rebel, a maverick, a cowboy. Boundaries are smashed, conventions blithely hurdled; wonders are accomplished, patients become friends. He is politically incorrect, and gleefully so. A brazen atheist and a gold-medal stirrer. He is also one of the most skilled and humane surgeons in the world.

On this bright summer day, Al Muderis is bouncing between four operating theatres. A knee replacement here, a complex limb-lengthening procedure there. “Walk with me!” It’s not a question. He gulps down hot coffee while scrubbing up between patients. Pushing his elbows through a new set of doors, rubber-gloved hands aloft, the doctor beckons me to follow. “There is so much to do and I’m running out of time,” he says, voice rising to a shout as the grinding screech of a bone saw resumes. “You live only once.”

The first time Al Muderis was certain he would die was in the autumn of 1999, nine years after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. He was 27 years old, working as a first-year resident at Saddam Hussein Medical Centre, a once-great Baghdad hospital that had fallen into disrepair following the years of economic sanctions imposed on Saddam’s regime by the United Nations. He was a child of privilege, born into an influential Sunni family said to be descended from a bloodline tracing back to the Prophet Mohammed. His father, Abdul Razak, was a lawyer who rose to become a Supreme Court judge; his mother, Kamila Al Turck, was a school principal who was demoted for refusing to join the Ba’ath Party. Munjed’s silver-spoon childhood featured holidays abroad, nannies and housekeepers. “I was a spoiled brat,” he says now. He was chauffeured to school, the same exclusive Baghdad institution attended by Saddam’s own thuggish sons, Uday and Qusay. From the age of 12, when he’d watched The Terminator and been gripped by the concept of cybernetic limbs, he’d wanted to pursue a career in orthopaedics.

Now, here he was, graduated from Baghdad University and, on this ostensibly routine day, completing rounds of the wards as a wet-behind-the-ears intern. He didn’t know it, but on this day he would cheat death, and events would be set in train that would see him tumble from the gilded top of society’s ladder to its lowest rung.

He was prepping with the rest of the surgical team when military police marched into the operating theatre and ordered them to cancel all surgeries for the day. Three busloads of army deserters were waiting outside and the police had orders from Saddam himself: the doctors were to amputate the rogue soldiers’ earlobes. When the lead surgeon refused, citing the Hippocratic Oath, he was dragged outside and shot dead in the hospital parking lot. “If anyone shares his view, step forward,” Al Muderis recalls an officer saying.

While his colleagues were immobilised with terror, Al Muderis stole away to the women’s change room, locked a cubicle door behind him and spent the next five hours flinching at every footfall. When he heard a group of nurses enter to wash up, he knew the mutilation surgery was complete. The guards had left; he had upheld his pledge to do no harm. But he was now a traitor. If found, he would be shot.

He took a taxi to the outskirts of the city and relatives helped smuggle him out of the country into Jordan, with a false passport and money from his mother taped to his stomach. From there, he travelled to Malaysia and on to Indonesia where he handed over his passport and about $2000 to a people smuggler. Things were moving quickly for the fugitive as he tried to navigate the chaos of the refugee world’s underbelly. He jumped to the head of a six-month queue when the smugglers realised the value of his medical credentials on a boat leaving immediately for Christmas Island with three heavily pregnant women on board.

And so the aristocratic young doctor, scion of one of Baghdad’s original ruling families, found himself crammed onto a perilously unsound fishing boat with 150 seasick asylum seekers. His possessions at this point: a dog-eared anatomy textbook and the clothes on his back. He would reach safe haven or he would die trying.

Every hour is rush hour at Macquarie University Hospital’s Limb Reconstruction Centre. Unlike the nearby surgical ward, with its antiseptic corridors, beeping monitors and buzzing fluorescents, the clinic is crowded, cosy and convivial. Patients with varying degrees of mobility stand, sit and wheel about, swapping stories and trading amputee life hacks. There are sandwiches and coffee. Today there’s a frisson of excitement: a TV crew is trailing a knot of fit-looking young men wearing fleece tracksuits and slightly bewildered expressions. They are three of the six Afghan athletes who refused to return home after competing in the Invictus Games and are now in Australia on bridging visas awaiting the outcome of refugee claims. All are former soldiers who lost limbs fighting with the Afghan National Army alongside the US-led coalition forces against the Taliban.

Al Muderis has offered his services pro bono; it’s hoped crowd-funding will take care of a further $250,000 worth of prostheses and other costs. “We do what we can to help these people because they are injured and everybody deserves to be treated,” he tells me after an interpreter-mediated consultation. “Also, they are here now and if they continue the way they are, they will be disabled forever and they will live on social security and that will have a negative impact on themselves and the overall Australian community. One of them is very motivated to become a mechanic and wants to work. One young guy seemed to be confused totally; I encouraged him to start studying, learn English. As long as he has a heart beating he should look at the glass as being half full.”

It was this determined positivity that buoyed Al Muderis on his journey through what he describes as Australia’s “dehumanising” refugee system. That leaky boat did make it to Christmas Island after a nerve-racking 36 hours at sea but, soon after, he was moved to the Curtin Immigration Detention Centre in Western Australia’s remote north. He had escaped a cruel and corrupt dictatorship only to touch down in a different kind of hellscape.

His autobiography, Walking Free, released four years ago, details “appalling” conditions at Curtin: chronic overcrowding, racial and psychological abuse, mistreatment of children and long processing delays that resulted in self-mutilation and suicide attempts. But it was a simple, three-digit number that nearly brought him undone. It was written on his arm in permanent black marker — 982 — and, for the 10 months he spent in limbo, tormented by boredom, targeted as a trouble-maker for fomenting unrest, he was deprived of his name. “Calling someone by a number is the most demeaning thing you can do to a human being,” he says now, adding that while he understands some form of detention is necessary, incarcerating a person indefinitely is inhumane. “People who have been vetted from the medical, criminal and terrorism side of things have a right to be processed for settlement,” he says. “It’s not a crime to cross borders if you are in fear for your life. I can’t talk about all refugees that come to Australia, but having been through the process, and the horrific boat journey, I think it’s ridiculous to assume that a person would come through that route as an economic migrant.”

Border protection is now shaping as a hot-button federal election issue. Al Muderis is bipartisan in his condemnation of the political parties’ approach; decision-making on both sides is clouded, he says, by a dogged focus on winning votes. “No one should have open borders but I think what we are doing is a temporary solution and it’s extremely costly,” he says. “Australia should have a cost-effective, humane and long-lasting policy that would allow us to keep face in front of the rest of the world and at the moment we are not ticking any of these boxes. As long as people fight, there will be people mobilised from one place to another because of persecution and danger. You can’t plug holes in a sieve.”

In August 2000, Al Muderis was finally granted asylum and found himself on the right side of Curtin’s barbed wire fence. Free. His mother mailed him a copy of his medical degree and he sent out 100 resumés to hospitals around the country. Within three months he’d been registered in Australia and, after a stint cleaning toilets, landed a job as a junior doctor in the emergency department at Mildura Base Hospital in far north-west Victoria. He’d made it off the bottom rung.

“At the time I was processed,” says Al Muderis, “of the 1252 people in detention 13 were doctors, all of whom have gained specialisations and are serving the community in Australia in cities and rural areas. And they are all paying taxes.” He worked hard in Mildura, earning a promotion to the Austin Hospital in Melbourne, where he married Doha, an Iraqi refugee he’d met on the boat to Christmas Island. They had two sons, Adam and Dean, but later divorced. (In 2006, he married a Russian-born GP, Irina, with whom he has two daughters, Sophia and Amelia, but they separated a year ago. He also has a grown son, Ahmed, with a woman he was briefly married to in Baghdad.)

Soon after qualifying in orthopaedic surgery, Al Muderis became intrigued by an emerging technique called osseointegration, and in 2009 he moved to Berlin for a year to explore the cutting edge of his profession.

Did you know: the rubber cap that protects the base of a fishing rod — pick one up at any tackle shop — is the perfect size and shape to crown the jagged metal tip of an osseointegration implant. “You just put ’er over the end and it doesn’t rip the bed sheets! It’s perfect!” says Blythe Warland, 55, who has been living with his new prosthetic leg for 18 months. Every couple of months he’s in Al Muderis’ clinic, regaling the waiting room with helpful tips and tales of triumph. Warland — cargo shorts, work boots, grizzled biker beard — came off second best in 1987 when his motorbike collided with a Northern Territory road train. Both feet were degloved and his left leg had to be amputated. Thirty years living with the discomfort and shortcomings of an archaic socket prosthetic came to an end when he underwent osseointegration surgery with Al Muderis in 2017. “I did lots of research but I just didn’t realise how much better it was going to be until I started walking on it,” Warland says. He kneads the puckered ridges of his stump. “I keep thinking, ‘How many Munjeds have we kicked out? How much potential expertise are we not getting because, for whatever reason, our government has said, ‘You’re not allowed in’. I’m not pro letting everybody in but, Jesus, without Munjed I’d be stuffed.”

Al Muderis, who also specialises in hip and knee replacements, has completed more osseointegration surgeries than anyone in the world. The operation essentially creates a bionic leg, or arm, that is integrated into the human body as bone tissue fuses with a titanium rod inserted into an amputee’s remnant bone. A high-tech robotic prosthesis then clicks onto the end of the implant.

Better. Stronger. Faster. “We are actually the start of cyborgs,” says Warland, gesturing at the crammed waiting room. “Because what is a cyborg out of science fiction but a machine with a human brain?” The former mine electrician now has a state-of-the-art bionic foot, with microprocessors that sense what’s underfoot and adjust flexion accordingly. He can’t believe the level of sensitivity the new leg has given him. “When I stand up and close my eyes, the leg moves exactly where I feel that it is. And you can feel through the bone what surface you’re walking on.”

“It feels like it’s part of your body,” agrees Kevin Harding, a former contract manager who offers peer support as part of Al Muderis’ multidisciplinary team. He takes an allen key out of his shoe and — click, twist — removes his right lower limb. “Takes less than a minute,” he says. “Handy when you’re trying on pants.” Harding, 66, was nine when he was hit by a car on the way to his aunt’s house in New Delhi, India. As he lay dazed in the street, a bus ran over his leg.

A year later, he was back playing cricket with the neighbourhood kids after having a wooden leg fitted. “But it was primitive,” he says. “Hand-carved from a block of wood, with a bolt through the middle, and it just hung off my waist from a cumbersome belt.” Al Muderis performed osseointegration surgery on Harding in January last year and “now I just lead a normal life,” he says. “I’ve set a goal, I do 10,000 steps a day; it’s fantastic.”

People lose limbs for all kinds of reasons: accidents, disease, infection. In Iraq, it’s mostly bombs. “Blast injuries are much more complex operations, because there is nothing from a textbook, nothing normal,” Al Muderis says. He welcomes the professional challenge, though — and that’s part of the reason why, in 2017, he started making regular trips back to his former homeland, where years of conflict have taken a terrible toll. As well as the injuries inflicted on soldiers and civilians by artillery shells, mortars and guns, the rise of jihadist movements has seen an increase in battlefield tactics calculated to maim as well as kill. Car and truck bombs, suicide bombers and other improvised explosive devices have left Iraq with a high number of amputees. “Children with blast injuries, they’re the ones that break your heart,” Al Muderis says.

He’d already operated on dozens of veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — including British soldier Michael Swain, who lost both legs after stepping on an IED in Afghanistan a decade ago and recently won medals at the Invictus Games in Sydney — when he received word from Iraq’s then prime minister Haider al-Abadi. He wanted Al Muderis to return to Iraq to perform his renowned osseointegration procedure on soldiers who had lost limbs in the battle against ISIS.

Al Muderis is Australian now, with few personal ties to Iraq. (His father died in 1995 and his mother in 2014, eight years after migrating to Australia.) He had never envisaged a return and was still wary of his home country, but the PM’s request triggered a sense of duty. The injured soldiers needed him. Judging by the throngs of desperate patients and their families who swarmed the hospital grounds soon after his arrival, civilians needed him, too. “I feel sorry for these people,” Al Muderis says. “Iraq has gone back to the dark ages. It’s a shithole and becoming a bigger shithole.”

The tales of trauma and heartache in his second book, Going Back, released next month, validate his decision. One of the first to be treated in Baghdad was a young former soldier who had lost a leg to a suicide car bomb; his wife had left him, concerned he would no longer be able to provide for a family, and he’d been left to raise their young son alone. In Iraq, losing a limb and becoming dependent on others can be worse than dying. There are few social support networks and amputees face unemployment, financial hardship and even open hostility. Al Muderis operated on a middle-aged man who had lost both arms but still worked each day. A young man who’d lost both legs after being hit by a mortar suffered a double blow when his girlfriend’s mother vetoed marriage because he was now disabled. The story that Al Muderis and his team have found hard to shake involves a former soldier who ran towards the site of an ISIS car bomb to pull a young boy from the debris. As they were fleeing from the scene another car bomb exploded in front of them and the boy, clasped to the soldier’s chest, took the brunt of the blast. The soldier lost most of his right arm; the little boy was killed.

The second most common patients Al Muderis sees in Iraq are children born with deformed limbs. “Sadly, the antenatal training in Iraq has gone back to the dark ages and the rise of the religious influence in Iraq has led to people having stricter rules about carrying on with pregnancies even if they know there are deformities with the foetus,” he says. “A lot of babies are born severely deformed and to make it worse their parents, through ignorance, take these children out of school and they end up with no hope in life.”

Al Muderis spent the past Christmas season working in Iraq, and tears spring to his eyes as he describes the plight of an eight-year-old girl he examined. “Sorry, I don’t get emotional very quickly,” he says. “But it upsets me every time I think of it. I treated a child with one leg that was extremely shorter than the other. She said she would love to go to school but her mother said they didn’t want her getting bullied so they took her out of school. I said, ‘You bunch of idiots.’ The society is so cruel, so harsh, the only weapon she will have is her education. They’re depriving her of a future. It’s criminal.” He will return to Iraq in April, and has told the girl’s mother he won’t operate on her daughter unless she is in school.

Heavy grey clouds blanket Darling Harbour asAl Muderis steps aboard his yacht, 17m of streamlined luxury that for anyone else would be a work-free zone. Silvery waters shift moodily beneath the hull. He’d been up operating deep into the night on an Iraqi refugee who’d fled the havoc of his homeland only to lose both arms in a workplace electrocution accident in Sydney. It’s Saturday morning. Decompression time.

But here comes Scott Griffin, a 46-year-old construction supervisor from Adelaide, a patient and, therefore, a friend. Griffin had osseointegration surgery in April after two years living with a socket prosthetic following a motorbike accident that took off his right leg above the knee. He’d been about to board a plane home when he noticed a component on his implant had come loose. “These things do happen,” says Al Muderis, opening up his surgical tool kit as Griffin settles onto a seat in the stern. “It’s just like fixing a flat tyre.”

Like many a pioneer, Al Muderis initially encountered resistance from the conservative establishment. Scepticism turned to professional jealousy as his database of proven and documented successes grew, but his surgery partner, Dr Kevin Tetsworth, suspects there was more to it. “There will always be people who look at him as an immigrant and an outsider,” he says. “Not that he’s actively discriminated against, but he’s never quite going to be part of the club. He also has an expansive personality; he is an easy target.”

And, yes, he’s got a million dollars’ worth of boat, he drives an Aston Martin and has put down $10 million and change on a yet-to-be-built harbourside penthouse. But he also devotes swathes of time to pro bono work in places such as Cambodia and Iraq, even frequently paying for expensive prosthetics out of his own pocket. “You have the house, you have the car, you have the boat, what else?” he asks rhetorically. “You can’t spend the money. You start spending it on stupid stuff. I’d rather leave something meaningful behind.”

He’s never off the clock where his patients are concerned. “The vast majority of them become very close friends,” he says. “I’ve been severely criticised by many that I breach the barriers with patients. To be honest, I don’t give a shit if I get deregistered because I don’t think it’s wrong.” Al Muderis, as much as anyone, knows how upsetting it is to be known as a number. “There’s nothing wrong with calling your patient by his first name and vice versa. And I’m a strong believer in empowering the patient to analyse the risks and benefits and make their own decision; we should not treat patients like children.”

Prosthetic secured, Scott Griffin steps off the boat for a trial lap of the Cockle Bay Marina jetty, a nuggety figure in bright red sneakers now parading a relaxed, stable gait. “Most of my patients are like Scott,” Al Muderis says. “Cheerful, happy to be walking.” Happy to be alive. “You can have positivity in everything; there is always a way to flip things.” Griffin climbs aboard, smiling. As the boat slides beneath the old Pyrmont swing bridge, he’s up on the top deck, resting his chin in his arms, inhaling the salt breeze. This harbour, on this day, sounds and smells and looks like heaven.

Going Back by Munjed Al Muderis with Patrick Weaver (Allen & Unwin, $32.99) is out on March 4.