Cinematographer Jim Frazier focuses on the planet’s survival

Jim Frazier has always been given the jobs in the too-hard basket and he’s always delivered. But can he change minds on climate?

Jim Frazier was chasing butterflies in the jungles of Borneo when he heard what sounded like the ghost of Miles Davis. A bright, golden note, playfully prolonged, led him through the sweating undergrowth to discover not a virtuoso trumpet player but a cicada. Tarantara! As a pioneering wildlife cinematographer, Frazier, 78, had spent his life getting as close as humanly possible to nature, capturing the grandeur and quirks of the animal kingdom, eavesdropping on its ancient languages. Hearing that wild cicada toot, it occurred to him how many creatures make sounds that resemble musical instruments. “If you listen to dolphins, they actually sound like violins,” he says. “And there’s a little bird with a very complex call that sounds like an orchestra in itself.”

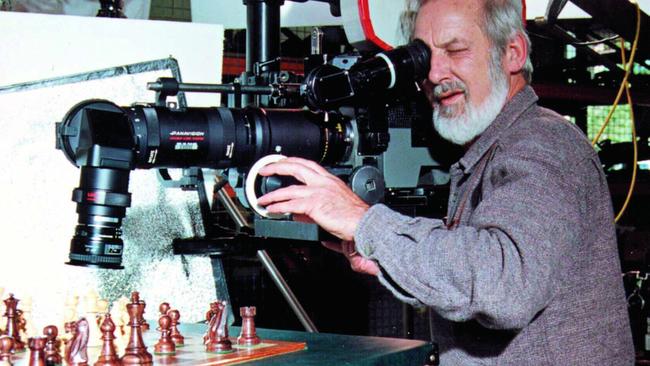

Frazier wears many hats: he is an artist, scientist, naturalist and inventor. As a cinematographer he spent decades crisscrossing the planet, most notably for David Attenborough, as well as for National Geographic and the ABC. He has an Emmy. And an honorary doctorate for contributions to science. In 1997, he was awarded a technical Oscar for the invention of a camera lens system that revolutionised movie-making in Hollywood. But he believes his most important work is ahead of him. In his eighth decade on Earth, Frazier has devoted himself to saving it.

From his modest home on acreage near Taree, on the mid north coast of NSW, he has spent the past 12 years orchestrating an ambitious film project called Symphony of the Earth. Cicadas will star, alongside drumming woodpeckers, hooting gibbons, thundering elephants and choruses of birds singing their hearts out. High-pitched shrieks, low-end blasts, peeps, cheeps and chatter: a vibrant collection of the animal kingdom’s greatest hits. The aim of this project? To reverse what Frazier sees as a prevailing view of the natural world as something to be subdued and exploited. “Because my whole life has been geared around wildlife, I’m very connected with the environment,” he says. “Long before global warming became an issue, I was talking about danger signals I’d witnessed around the world.” The decimation of rainforests, depletion of the oceans’ food sources, rubbish in the rivers, plastic on the beaches — it’s all building to what Frazier calls “a man-made extinction event”.

“We’re all disconnected and until we reconnect back with nature, I can see it all going wrong,” he says. Attenborough concurred at the UN climate conference in Poland this month, telling world leaders that time was running out to act on climate change. Frazier doesn’t want to preach. Symphony of the Earth will be less a pointed critique of society than a reminder of the beauty and interconnectedness of all things. The story will be in the music.

Eight peacocks strut the grounds of Frazier’s Manning Valley home, 22ha of bush that he and his wife Helen have established as a haven for koalas, butterflies and more than 160 species of birds. As we sit talking on a sun-striped patio, one of the peacocks makes a noise I’ve never heard before as it seeks to bedazzle a mate: a soft susurration caused by the rapid vibration of its impressively splayed tail feathers. It’s known as “train-rattling”, it employs complex biomechanics, and it nicely encapsulates Frazier’s vision for his film: arresting visuals working in harmony with sound.

Non-narrative, non-verbal film has been done before: mood bombs such as Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Baraka (1992) and 2012’s Samsara took audiences on meandering explorations of nature and human existence. Frazier’s concept is similarly epic. Koyaanisqatsi was propelled to great emotional heights by a sweeping Philip Glass score. Symphony of the Earth will rely for its power on something entirely new: a rich diversity of animal sounds, captured in the wild and then arranged by composers into songs. Animal music. “I plan to send the best wildlife cameramen I know all over the world to capture and record native species,” Frazier says. All the sounds of a conventional orchestra — strings, percussion, woodwind and brass — are playing non-stop in nature, he says. “Then composers will incorporate the sounds so they’re integral to the music, not just a sound effect.”

Frazier’s dream depends on fundraising and donations of time and talent. “It’s a matter of building an enormous groundswell among people,” he says. Quixotic? Perhaps. But there’s something pleasingly old-fashioned about this vision for a big-screen “Woodstock of the cinema”, a creative collaboration between man and nature. Poised between the two worlds, Frazier sees it as his calling to act as ambassador from one to the other. “I have six grandsons,” he says. “And that is my driving force. I feel I can’t leave this planet until I do this project. The average person might think, ‘Are you a bit tweaked in the head?’ But I’ve done things before when they said it couldn’t be done. I’ve always been a left-field thinker. I’m not governed by convention.”

Growing up in Armidale, NSW, Frazier spent every weekend in the bush with his butterfly-collector father. The boy discovered he had an intuitive way of interacting with nature that bypassed reason; he’d often sense what a creature was about to do before it happened.

An early job working in the zoology department at the University of New England led to a stint in the 1970s as chief preparator at Sydney’s Australian Museum, where he met naturalist and photographer Densey Clyne. Frazier was not a photographer. But when Clyne asked for his help filming the insects in her garden, he bought a second-hand 8mm movie camera and taught himself on the fly. The pair next collaborated on a spider documentary, Aliens Among Us, which sold to the BBC and kicked off a decades-long association during which they travelled the world filming for David Attenborough’s TV series Life on Earth, The Living Planet and The Trials of Life.

They visited the rainforests of Sumatra to film the blooming of a rafflesia, the world’s largest flower. Borneo, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea. The Sierra Nevada mountains in California to capture the antics of the yucca moth. And the red dunes of the Australian Outback, where they managed to film a rare marsupial mole. “You’re forever an opportunist in wildlife filmmaking,” Frazier says. “If you see something happening, you shoot it.”

His intuition — he calls it a sixth sense — meant he could capture on film what others could only dream of. “When I was filming for Attenborough, the BBC would always give me the ‘too hard basket’ stuff to shoot and I always delivered,” he says. “There have been about 10 cameramen who’ve had a go at the birth of a koala; no one had ever got it. I went up to Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary [in Queensland], where they knew this one koala had mated 30 days before. I stood there and watched it and all of a sudden I just saw this little blinking of the ears. I knew instantly it was starting to give birth and I was able to film it.”

In the late 1980s, Frazier grew frustrated with the limitations of existing camera lenses and set about inventing his own. “I’d had to fix cameras on the job in remote places, so I’d learnt to troubleshoot, pulling lenses apart and playing around with the optics,” he says. He consulted a CSIRO physicist about how to get an extreme “depth of field” so that foreground and background objects in a shot — everything from macro to infinity distances — would be simultaneously in focus. Impossible, he was told. But the persistence that had once led Frazier to spend two months in a tree waiting to shoot footage of mating riflebirds paid off with the invention of what is now known as the Academy Award-winning Frazier Lens. Steven Spielberg and James Cameron were early adopters, on Jurassic Park and Titanic respectively, and the lens is now commonly used in movies and commercials throughout the world.

With the right light, a bespoke lens and a stabilising touch of awe, Jim Frazier has, over four decades, been able to document thousands of extraordinary creatures performing remarkable feats. He’s gone places they said he couldn’t go; done things they said couldn’t be done. If he says his plan for his film is to “change mankind’s thinking”, it’s a brave person who would challenge him.

“It’s all about future generations and their survival,” he says, raising his voice above a nearby outbreak of cheerful finch warbling. “If we keep on the path we’re on at the moment, they’re staring a very bleak future in the face. I think if you have enough passion, you can do anything.”