Bicentenary baby: the life and times of Zoie Carroll, 30

She was born in the bicentennial year. Zoie Carroll’s life tells the story of our times.

Zoie Carroll was born on an ambulance gurney at 11.10am, February 24, 1988. She has always considered her birth a uniquely Australian event defined by the fact that her mother, Robbie, never quite made it to the maternity ward of St Margaret’s Hospital, Darlinghurst, on account of the scratchy beach sand stuck inside her brothers’ swimmers. During that summer of 1988 her family was living in a house in Hunters Hill on Sydney’s lower north shore that her property developer father, Gerard, had built with his brother overlooking a gentle inlet and a patch of sand near the ferry wharf.

“My two older brothers, Ryan and Byron, were playing on that sand that morning,” she says. “Mum said she was running late for my birth because she had to wash the sand out of my brothers’ swimmers. They were crying and they insisted she did that before she left to go have me. She didn’t make it to the hospital and I was actually born on the ambulance trolley.”

Robbie was that kind of Australian mum. Always putting everybody else first, squashing her own hopes and dreams somewhere down deep inside herself in the process, somewhere deep and close to the great family secret she kept from Zoie for too many years.

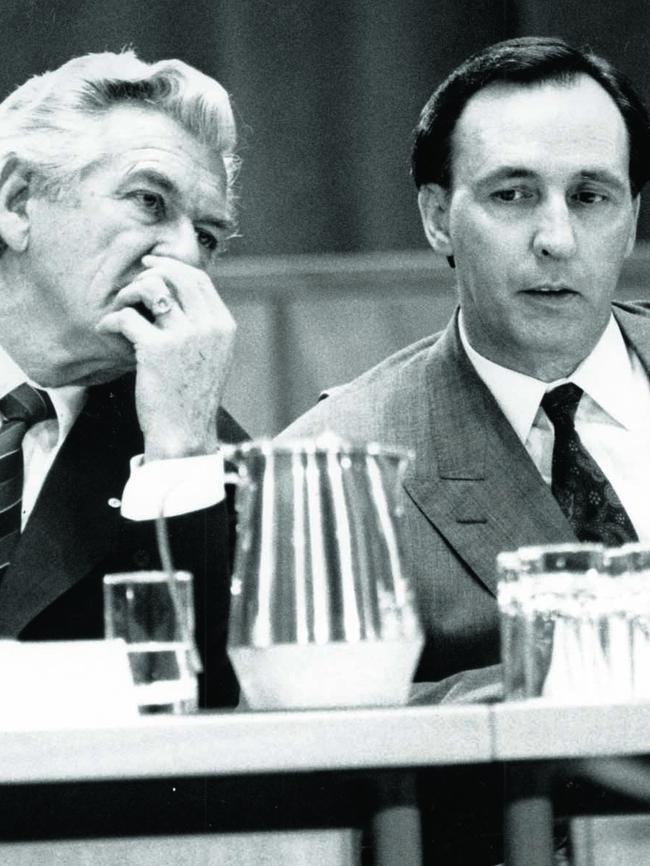

Zoie was three years old when Paul Keating replaced Bob Hawke to become the 24th prime minister of Australia. She was four when the High Court delivered its Mabo decision determining that native title did exist. Zoie’s world then was only as big and long as the houses and street signs and shopfronts she saw from the window of the bus that took her from outside the local fish and chip shop to preschool where she learnt to write her name. She started primary school at Sacred Heart Catholic School, Mosman, in 1993, the year Shane Warne bowled his “Ball of the Century”, The Piano won three Oscars and the Australian dollar slumped to its lowest level since 1987, prompting a rescue intervention by the Reserve Bank.

Zoie ate osso buco for dinner. Lamb shanks and pork roast and fish baked in foil with white wine and butter. She recalls an Australian Women’s Weekly cookbook permanently open on the kitchen bench and Robbie’s recipes became more exotic as the 1990s wore on — beef stir fry, butter chicken, Thai green chicken curry — but the pavlova always stayed the same.

She was a Nickelodeon kid. She was a product of subscription television services introduced to Australia in 1993. She was a Rugrats kid. She worshipped Captain Planet and the Planeteers, a cartoon response to the world’s growing environmental awareness that saw Captain Planet and a team of environmental warriors assembled by the spirit Gaia to battle a series of supervillains hellbent on polluting the world.

Some days she’d have to turn the volume up on Captain Planet because her mum and dad were arguing in the kitchen, often about money. She wondered why her dad worked so very hard to make more and more of the thing that seemed to cause most of the problems in their home. Soon she grew to hate the money as much as she hated the fighting. Some nights she’d lie in bed trying to recall a single kind thing her parents ever said to each other. The divorce papers were finalised when she was 10 years old, 1998, the same year the most powerful man in the world, US president Bill Clinton, was denying he’d had “sexual relations” with a White House intern named Monica Lewinsky.

Zoie had her first kiss in 2000, the year the Olympics came to Sydney. It was her first year of high school at Loreto Kirribilli. The setting for the kiss couldn’t have been better: a family friend’s house in Woolwich on Sydney’s lower north shore. It was night and there was a party. Two pre-teens by a jetty and a big round tree covered in fairy lights. The kiss itself, however, wasn’t what Dawson’s Creek had led her to expect. Her girlfriends demanded a one-word assessment. “Slimy,” she said.

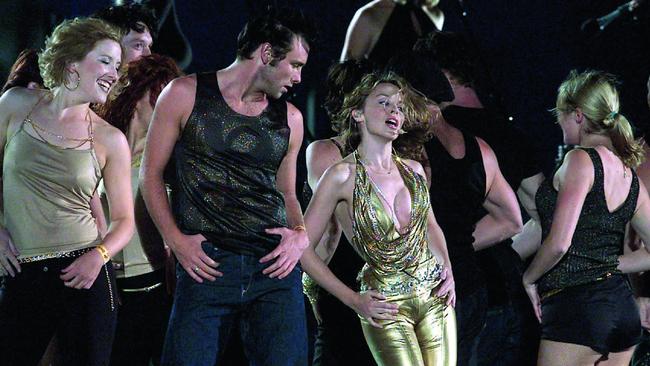

She saw her first concert that year. Kylie Minogue. She was into running and rowing at school. She saw Cathy Freeman run for her life at the Sydney Olympics, but at 12 years old Zoie didn’t know what that race meant to Australia. She didn’t know why all the adults around her saw that 400m golden run as so significant because all she saw was a great Australian in a cool running suit. She didn’t see the colour of Freeman’s skin because Zoie and most of her friends her age were socially colour blind. They did not question race but they questioned religion.

“I remember my school principal took a class of religion as a relief teacher,” Zoie says. “There was a dare to lock her out of the room. I never turned down a challenge and I locked her out of the classroom and she was like, ‘Open the door’. And I was like, ‘No’. She was like, ‘Zoie, OPEN THE DOOR NOW!’ And I said, ‘No’.” There was so much wrapped up in that event. Her mum and dad not making it work. The religious education she was struggling to believe in. She was always on the outside of life looking in on the adults in her world and for that brief moment the school principal — the most adult of them all — was on the outside of the classroom looking in on her.

She had a Nintendo 64 games console in high school. She had a Sony CD player handed down from her brothers and then a chunky Apple iPod that stored her favourite Jennifer Lopez and 50 Cent songs. She had a Nokia 3310 mobile phone for emergencies and tapped lengthy messages to friends about boys using a keypad that forced her to scroll laboriously through the alphabet.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, she woke up in her mum’s house in Manly. She turned on the television to see a plane fly into the World Trade Centre. “Mum,” she called from the living room. “Look what’s happened.” That day, Zoie’s class had an excursion to the Sydney Jewish Museum in Darlinghurst. It was a cold, grey, windy day in Sydney and the class marched silently through halls dedicated to the time Nazi Germany murdered millions of Jews. They later gathered for roll call under the Harbour Bridge where Zoie — her mind filled with the tragedies of New York and World War II — looked up at the bleak skies and saw nothing but the apocalypse. “This is the end,” she told herself, and she felt sad because she had so much more to achieve, so much more to give back to the world.

She worked odd jobs through high school. She made flyers touting her babysitting abilities and handed them out to wealthy young parents on Manly Beach. She delivered pizzas and was always late to homes she could find only through a well-thumbed Sydney street directory and not Google Maps. She worked in music festivals. She worked so long in a fish and chip shop that today, the smell of a potato scallop cooking in hot oil makes her want to vomit. Every dollar she made she secretly stashed beneath her mattress in her bedroom. Each night she counted her earnings and dreamt of the places she was going. London. Paris. New York.

Her final year of high school was in 2005, the year of the Cronulla riots and the London bombings and Lance Armstrong’s seventh consecutive Tour de France win. This was the year Zoie began to see her generation being swallowed up by Self. Textbooks were being closed, pocket mirrors were being opened and the social media monster of Facebook was spreading towards her from a Harvard University dorm room. She didn’t know why she needed to feel attractive but she did. She found herself watching television with friends and family, each person buzzing inside an abdominal toning belt purchased from daytime infomercials.

“My brothers were early adopters of the health craze that engulfed our youth,” she says. “They’d take these pills called Fat Blaster tablets — they were appetite suppressants. So I took those and I remember I wasn’t hungry. They speed up your heart rate and blood pressure and, looking back, it’s just so unhealthy and I had no idea what I was doing and I was a teenager. I was preparing madly for my exams but also fasting and I was on this ridiculous diet to try to lose weight so I could look good and fit into my dress for my school formal. That was when I really noticed the glossy magazines: J-Lo lost 10 kilos in two weeks and you can too. I was easily influenced and impressionable. Maybe I could do the same thing but I’m only 16. I wanted to feel more accepted. I wanted to feel more beautiful.”

But who for? she asked herself. Surely not the boys in all those school formal dances with their sweaty palms and their stilted talk and their smelly underarms. Who for?

Not long after her high school graduation, she walked into her bedroom, closed the door behind her, lifted her mattress and counted up her savings from her years of doing odd jobs. She had been sleeping on $25,000.

She travelled to London in 2006, the year Steve Irwin died. A killer exchange rate saw her savings disappear quickly. She dropped CVs into 10 bars across London and the eighth bar gave her work and the people in the bar gave her enough tips so she could not only pay board in a London hostel but she could eat at night. She was living as a nanny in France in 2007 when Kevin Rudd defeated John Howard to become the 26th prime minister of Australia. Zoie returned to Australia at the age of 21 and dived into a Bachelor of Business degree at Bond University on the sunny Gold Coast.

She was 24 and working as a property consultant in Dubai when her world fell apart. It was 2012. It was the year prime minister Julia Gillard apologised to Australia’s victims of forced adoption. It was the year the Curiosity rover landed on Mars. It was the year of Gangnam Style. It was the year Barack Obama was re-elected president of the United States. It was the year Zoie’s mum, Robbie, took her life.

She thought the person on the phone had the facts wrong. She thought it was a sick joke. She flew back home to identify her mother’s body in the morgue and she couldn’t keep her body still. Her loved ones described her that day as running around the room like a cat. She never said a proper goodbye to her mum. She simply left the room saying, “Goodnight, Mum”, like she might have just tucked her mum in for bed.

There was so much wrapped up in that event. Robbie left no letters, no explanation. She left a book of 365 quotes — one for each day of the year — and on February 24, Zoie’s birthday, she left a brief note of love for Zoie, who channelled her deep grief into deep investigation. “It was like I put this detective cap on,” she says. “I had to know where she was when she died. What time was it? Who did she last speak to? Who was she with? It’s a difficult thing to process. This is your mother. This is the person who brings you into the world.”

There was too much that Robbie talked too little about. She’d given birth to a son when she was 17 and been forced to give him up. “But we weren’t to know that for, like, 20 years later,” Zoie says. “I think Mum really probably never dealt with the fact she had that child and I think it ate away at her for a very long time and she was quietly suffering. I met him on the day of my mother’s funeral. He’s a lovely guy.”

There was so much left unsaid. So many low points, Zoie thought, that could have been reversed with a decent open conversation. Robbie left Zoie a considerable inheritance and Zoie sat on that money like she had sat on her earnings in her teens. Then she put the money passed down through tragedy into something beautiful: an online community focused on reducing mental health stigma. A simple forum for people struggling with mental health issues to share stories about their low points, their darkest hours and their quiet triumphs. She called it Zottie Dottie — the nickname Robbie gave Zoie as a toddler, inspired by Zoie’s love of polka dot dresses. Today Zottie Dottie reaches 900,000 people across 27 countries.

“I’m trying to cut through all the BS that’s out there,” she says. “We’re seeing young people sharing these social media photos for these heightened social media lives, showing how beautiful and perfect their lives are when in reality we know that’s not always how it is. I was so exposed to a version of this in 1990s Australia.”

Her father had questioned her efforts with Zottie Dottie. “No one’s gonna care about other people’s problems,” he said. Then last year he watched Zoie receive a Queensland Young Achiever Award for Leadership. It meant so much when her dad looked at her with such pride that night.

S

he juggles her Zottie Dottie commitments with her day job as a business adviser for the Fiji Consulate and Trade Commission. She recently ended a long-term relationship with a man who she’d been to primary school with. It ended, in large part, because she wasn’t ready to start a family. There’s so much wrapped up in that, starting with the story of her fractured family environment. “I think the walls have gone up if I’m being honest,” she says. “I let work take up a large majority of my time and efforts and energies. Last night I went to a Sydney Swans game and my friends were like, ‘You’ve got to let people in, people are never going to want to talk to you if you don’t let them in’.”

She’s thought about using dating apps to meet her dream bloke but she feels out of step with a world that has turned romance into a choice between swiping right or left. She sparked up a random conversation at a bar recently with a man and he seemed genuinely shocked. “Are you talking to me?” he said, aghast.

But she sees motherhood in her future. She sees kids somewhere in the story of her next 30 years. She sees herself running around on some glorious patch of Australian sand with some kids whose only problem in life will be the scratchy sand caught inside their swimmers.

Her 30th birthday on February 24 this year landed on a Saturday. A series of militant attacks killed 20 people in Afghanistan that day. The United Nations Security Council unanimously approved a resolution demanding a 30-day ceasefire in the Syrian Civil War. And Zoie sat down for lunch with 20 good friends to celebrate her birthday at a restaurant in Double Bay. She and her mum had wanted to go there when Robbie was alive but they couldn’t make it work.

One of her best friends, Lizzie, made a speech that day. She spoke about Robbie. She spoke about Zoie’s 30 years on this Earth, the girl she was and the woman she grew into. “She’d be so proud, Zoie,” Lizzie said. And Zoie could have frozen that moment right there and lived the rest of her life inside it, never having to experience anything but the feeling that had overtaken her heart and mind and soul. Gratitude. But the moment passed and, to the sound of clinking wine glasses and silver knives scraping on lunch plates, the rest of her life began.