The outsiders: How Prince Philip and Diana were alike

The young naval officer was seen as the Diana of his times; a modernising force to drive a musty establishment into the 20th century.

Viewed through the prism of the woke, gender-fluid, cancelled culture of the 2020s, Prince Philip seems an anachronism: epitomising the rigidity of the British establishment of which he was at the heart. At times brutally strict, famously rude, outwardly emotionally sterile and unswerving in his duty to the crown, he would seem out of step, out of place in today’s world.

But that picture could not be further from the real man, the man the public seldom saw. In fact it was Philip who dragged the monarchy out of the 19th century, who encouraged Britons to see themselves as innovators, who despised the stuffy elitism of the world he entered on his marriage to the young Princess Elizabeth.

Even before the royal wedding in 1947 and in the early years of Elizabeth’s monarchy, the young naval officer was seen as the Princess Diana of his times; a modernising force, the man who would, some hoped and others dreaded, drive a musty establishment into the 20th century.

Philip blew into the tightly enclosed institution like an unwelcome gust of Arctic air blowing away the cobwebs of the previous century. He envisaged a less stuffy, more popular monarchy, more relevant to the lives of ordinary people and the elitist courtiers hated him for it, bullying him and patronising him as an outsider.

But he ignored their jibes although, as his friend Lord Brabourne said, they must have hurt: and went on to dominate, modernising not just the royal family but the world around him. The Times acclaimed him as a modernist in step with the current world. Others would credit him with helping the British see themselves as modern and innovative people.

At one official event he told an obsequious woman: “I don’t like to be ‘highnessed’. This is the 20th century. You’re not at King Arthur’s court, you know.”

At a lunch for the Foreign Press Association in 1964, the then 43-year-old Philip was asked if the monarchy had found its place in the Britain of the 1960s.

“What you are implying is that we are rather old-fashioned,” he responded. “I entirely agree … the monarchy is an old-fashioned institution. The interesting thing is that it is not a monopoly of old people.”

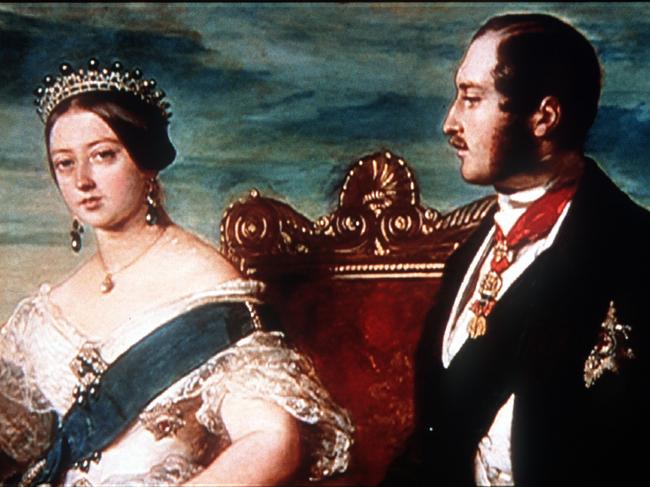

A better comparison than Princess Diana is, in reality, that of Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert. Both men were outsiders (although Philip mockingly referred to himself as a “refugee husband”) who forced an implacable institution to become more a part of their time than of history. There are other parallels too.

Albert is widely credited with having placed the organisation of the royal household on a stable footing, ensuring it operated within budget with a streamlined and efficient staff. He also began the professional management of royal collections and properties.

Nearly 100 years later, Philip would modernise Buckingham Palace and take over the management of the royal estates, turning the farms at Sandringham and Windsor into profitable concerns and supplying the royal households with food.

Both were also renaissance men; Albert was a modernising force in education and promoted the arts while Philip became a galvanising force in areas as diverse as science, design and conservation.

As early as 1952 he saw the potential of radio and television, predicting they had “gone beyond the stage of being amusing and entertaining novelties”.

He became the first member of the royal family to host his own TV program – a documentary about his Commonwealth tour, with footage he had shot himself. And he acted as producer for the Queen’s first televised Christmas broadcast in 1957, tutoring her on how to use the autocue. He also helped relax the nervous Queen, cracking a silly joke just before she went on air.

In other ways, though, he was like Diana, with their shared irreverence for an institution that was set like concrete in its ways, clinging to stuffy, outdated protocols.

Diana famously outraged courtiers by roller-skating through the corridors of Buckingham Palace, but four decades earlier Philip scandalised them by chasing a giggling Queen through the same corridors, wearing a giant set of false teeth.

Diana was lauded for educating her children in the public school system rather than in the palace, as was the royal tradition. But Philip had also broken with that tradition, sending Prince Charles to his own old schools – Cheam Preparatory School in Berkshire and then Gordonstoun in Scotland. Charles’ school years were unhappy but Philip had wanted his son to be exposed to a more egalitarian environment than Eton. He was suspicious of Britain’s public schools, which he believed smacked of unearned privilege – the privilege of birth rather than merit.

More unusually, Philip also became the first royal to be present at the birth of his child – in this instance Prince Edward – after being barred from the births of his three older children. Edward was a week premature and, perceiving that the medical team was anxious about the delivery Philip, typically, turned to jest to relax them.

The bathroom of the palace’s Belgian suite had been converted into the delivery suite and Philip told the team: “It’s a solemn thought that only a week ago General de Gaulle was having a bath in this very room.”

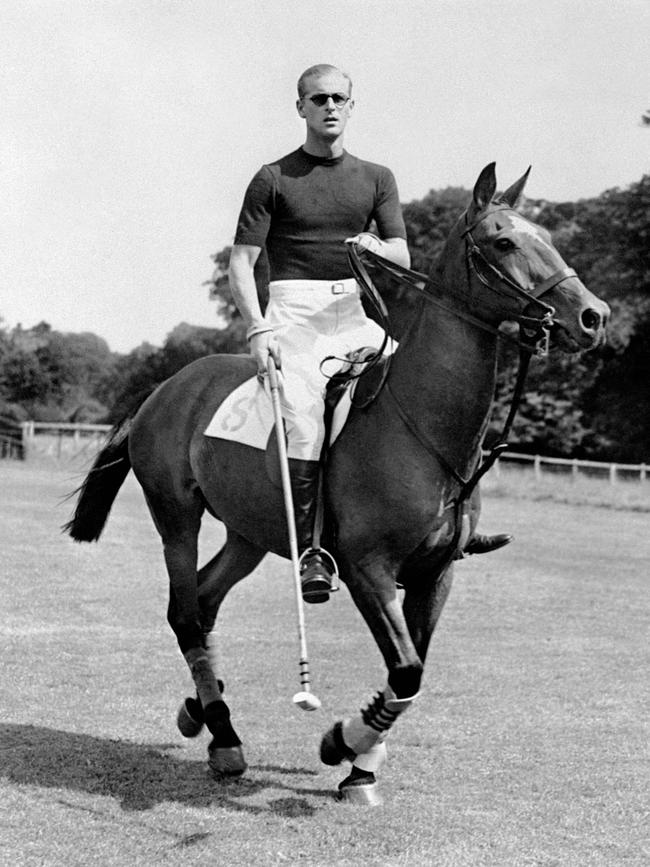

Philip refused to give up his personal interests when he married the Queen; they ranged from polo, sailing and flying to art and cooking. For years he took an electric frying pan with him everywhere to cook breakfast for his wife and it was he, rather than the Queen who organised the menus for state banquets at Buckingham Palace.

He was a keen conservationist: while Charles is well known for his views on climate change, Philip was warning as early as 1970 of the threat man was posing to the environment, declaring in a speech in Strasbourg: “We must decide how much pollution of the air, the land and the water we are prepared to tolerate. … We cannot postpone decisions any longer. Time is fast running out.” He also warned about the exploitation of fish stocks years before it became an international concern — although he drew the line at wind farms, describing them as “useless” and the turbine industry as being reliant on subsidies. He was fascinated by philosophy and psychology, religion and science – and engineering, which he believed of critical importance. But he was also interested in UFOs, subscribing to the Flying Saucer Review and corresponding with Timothy Good, a well-known ufologist.

His status as an outsider, and the appalling treatment meted out to him by palace courtiers made him sympathetic to his children’s spouses, despite views to the contrary. While Diana and Andrew’s wife, Sarah Ferguson, would go on to complain of their unsympathetic treatment at his hands, he at first welcomed them and tried to ease their way into the family as no one had eased his way.

As Diana’s marriage to Charles became troubled, she poured out her troubles to Philip, and he wrote her surprisingly affectionate letters of advice, explaining that he knew first-hand the difficulties of marrying into The Firm as the family call themselves.

But because he gave up so much for his wife and the crown, putting duty above all else, he expected both his children and those who joined the royal family to show the same loyalty. And when the young women put their own happiness before their duty, he was implacable; they had not just hurt the monarchy but his wife, and that was unforgivable.

By the time he retired in November 2017, Philip was patron and president of more than 780 organisations, using his position to champion causes from saving wildlife to helping youth; most notably through his Duke of Edinburgh Award scheme, which has helped millions of young people all over the world.

But to many, he would always remain the irascible, gaffe-prone prince who represented all that was bad about an outdated institution that had no place in the 21st century. Philip didn’t seem to care about how he was seen or how he would be remembered. “I am not really interested in what goes on my tombstone,” he once said.

His friends disagree. Shortly before he died in 2001, Philip’s good friend and former equerry, Australian Mike Parker, said: “I only hope the United Kingdom shows its gratitude for what he has done …. They’re the most extraordinarily lucky country to have him.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout