The odd Olympics: how our medal hopefuls are preparing for Tokyo

The Tokyo games, starting in three weeks’ time, will take place under a cloud of uncertainty. How are Australia’s great hopes preparing?

“There are known knowns,” former US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld famously declared about the hunt for Iraq’s weapons of annihilation that didn’t exist. “There are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” (Note to younger folk: we went to war for this.)

This year’s games in Tokyo, as far as Olympics go, will be the Mother of all Unknowns. The games should have been done and dusted by now and medals mounted in the good room. It was postponed for a year because of the pandemic and even now, less than three weeks from the opening, if there is a major outbreak in Japan things could get dicey. Already there’s a cloud of internal resentment – a recent poll in the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun stated that 83 per cent of residents believed the games should be postponed or scrapped. “It is simply beyond reason to hold the Tokyo Olympics this summer,” the newspaper, an official sponsor, said in an editorial.

The world has been in lockdown and chaos for the past 18 months. There have been few international events to allow athletes to gauge where they sit in the pecking order. How will this lack of competition affect the performances of individual athletes when they reach the world’s biggest stage? How will these odd circumstances favour some athletes over others? Will the near-empty stadiums be a disadvantage to some of the super egos best fuelled by a crowd? And what about conditions in the Olympic village? How will the hyperactive cope, cooped up like pigeons in their rooms, desperate to explore? What if there’s an outbreak among the athletes? What if, what if… The normal, at these games, will not apply. Sydney was famous for its overflowing bowls of condoms in the athletes’ village. If there’s an outbreak in Tokyo, the personal protective gear could cover the entire body.

Tokyo will be an Olympics for pragmatists, says 23-year-old sprinter Rohan Browning. And for that he’s glad. “There is going to be so much strategy involved in these Olympics, off the track. The most critical thing at these games will be not contracting Covid from another athlete in the dining hall or in the village. You get it, you are out. You are not competing. Your games are done.”

The stakes are high butBrowning reckons the seductions of the Olympic village will be too much for some. “It’s like being in a candy store,” he says. “There’s a dining hall with all these international foods open 24/7. You’ll have games rooms and there’ll be this festival atmosphere.” Temptations will abound. The sensible will sit it out in their rooms but others will be drawn to the fun.

Browning, meanwhile, will be tucking into a good novel, catching up on his law studies or Zooming his girlfriend, mates and family. “I’ll be there to get the job done and I’m very happy in my own company,” he says. “I am very pragmatic and I know what I have to do.” He adds: “I love having the crowd there cheering, it is such a special thing. But they may as well not be there. When I stand behind the blocks it is totally internal for me. I am just focused on what I can do and what I can control, and the crowd has no bearing on that.”

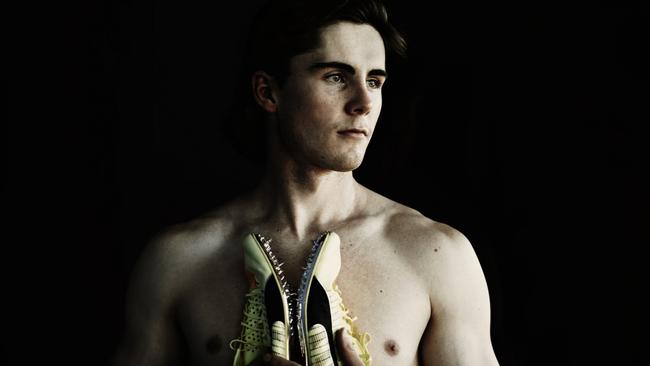

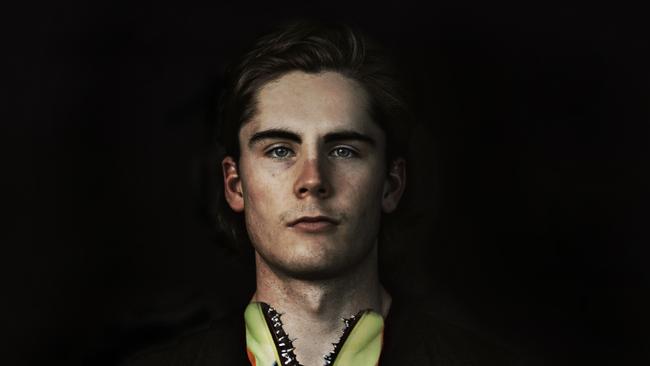

Australians may crow about our heroics in the pool, but the 100m track sprint is undoubtedly the premier event at the Olympics. To be crowned fastest man or woman on Earth is the Everest of sporting achievement. It’s the most competitive event in sport. As Browning points out, every athlete starts out running the 100m. Those who fail move to other pursuits.

For those who persist, the road is rocky. No Australian man has run fast enough to even qualify for the 100m sprint at the Olympics since 2004. The last Australian male to win a medal in the event was Hector Hogan who won bronze way back in 1956. The only other men’s medal was also a bronze, won by Stan Rowley in Paris, way, way back in 1900. The women have fared much better. The great Raelene Boyle was narrowly cheated of gold by a doped-up East German at Munich in 1972. Betty Cuthbert flew home to win gold in Melbourne in ’56 with Marlene Mathews taking bronze. It mirrored the result of four years earlier, in Helsinki, when Marjorie Jackson took gold and Shirley Strickland bronze (she also won bronze in London in 1948).

But as these dates show, our glory days in the event have long passed – our last medal came 49 years ago. And now, in Rohan Browning, we have a sliver of hope. If he runs the perfect race, if he makes the final, he might be in with a shot.

That it should be Browning carrying this torch is completely unexpected. He was always fast, but never the great standout. He was no Diego Maradona, the soccer star who had the glow of greatness the moment he stepped onto a pitch. “My mum sent me a photo the other day,” he says, as we sip coffee, not far from where he lives in a student share house in Sydney’s Surry Hills. “It was from the 2013 Under-18 NSW championships, the 200m final, and I ran dead last.” He shows me the photo of the scoreboard and there I see eight names ahead of his in the nine-person race. The winning time was almost two seconds faster than his effort. “I was flicking through the names of all the guys who beat me and I can’t remember any of them… none of them is running competitively now.” Among them were the Nick Kyrgioses of the world, sportsmen with talent to burn but without the grit to match. Browning’s always been more the Lleyton Hewitt type, stretching his abilities as far as they possibly can be stretched, fighting for every point as though his life depended on it.

And yet we may never have heard of him if he wasn’t so bright. Browningattended a school in Sydney’s Sutherland Shire until Year 9, when he won an academic scholarship for the elite Trinity Grammar. He loved it, not only for the educational opportunities but because it was a rugby school and he loved the game – he was a flying, try-scoring winger. He was always fast but not much into athletics; he did a year of Little Athletics in primary school but dropped it because it was too boring. “I was always a team sport kind of guy.”

One day at Trinity the school’s laconic athletics coach, Andrew Murphy, was walking past the rugby fields when he saw Browning take off. “I saw him running on the paddock and thought, ‘This kid’s not bad’,” says Murphy, who had been an elite sportsman himself, having represented Australia in the triple jump at Atlanta, Sydney and Athens. “I just asked him if he would be interested in coming along to a sprint session. He turned up and that was the start of a nine, 10-year relationship.”

Browning is the most dedicated of athletes, says his coach. His motivation comes from within. The fact that he was starting late didn’t bother Murphy. “Some of the best athletes of all times have been pretty average as kids. Carl Lewis was an absolute dud when he was young.” Had Murphy not walked past the rugby oval that day Rohan Browning would probably still be playing rugby. But under Murphy’s strategic and thoughtful coaching, he has thrived. “Murph is a great technical coach and a great mentor,” says Browning. “But he’s not a motivator. And so for that reason I’ve always had to be self-motivated and I think that suits my character.”

His mother, Liz Jackson, seems bewildered that she’s spawned an elite sportsman. Jackson, a former ABC journalist who used to present Saturday AM on ABC radio, is anything but the pushy tiger mum. Neither is his dad, Andrew Browning, a former army tank driver, policeman and now investigator with NSW ICAC. “I’m as perplexed by it as everyone else,” Jackson says, with obvious pride. She’s watched him get to the Olympics through sheer determination. She references US psychologist Ellen Winner, who talks about certain children having “a rage to master”, and says her gentle, loving son has a burning rage within to run as fast as he possibly can.

Jackson says her son thrives on the “accountability and the vulnerability” of running. The accountability is that his results are entirely dependent on his own efforts. The vulnerability? She has quizzed him on what the pressure is like at the starting line. He calls it the vulnerable place. “He loves that vulnerable place because of its possibilities,” she says. “That’s how he sees it… he’s not the sort given to meltdowns or panic attacks. He’s very cool. Very balanced… in vulnerability he sees possibility.”

In 2014, the year after he ran last in those state championships, things started to change. He was putting in a huge effort and the results were showing. “I was 16 going on 17,” he says. He was in Year 11, still playing rugby, but disappointed that he wasn’t picked in the school’s First XV. “I was a bit jaded and I thought that if I could make a national final it would add a few extra points to my ATAR and take the pressure off when I got to Year 12,” he says. (In the end it wouldn’t have mattered – he got an ATAR of 99.45).

What he discovered was that the harder he trained, the faster he ran. In March he ran 11.13. Then he ran a sub 11.00. Then he won the NSW Combined High School Final. He then ran 10.39. “I just had the most absurd progression, like just unheard of,” he says. He realised that if he trained very hard he could be very good. He channelled the rage. And that’s what he’s done, year after year.

And now he’s in peak condition. He says the Covid lay-off was good for him. Not travelling for competition has meant he’s been able to concentrate on training and building his strength. In January this year, with a slight breeze at his back, Browning ran 9.96 seconds at the Illawarra Track Challenge, becoming only the second Australian ever to break the 10-second barrier after speedster Patrick Johnson first cracked it back in 2003. Unfortunately, the 3.3m/s wind at his back meant the run was deemed “illegal” as an official time and could not be used as an Olympics qualifier. But in April, late on a cold Brisbane night, he ran 10.05 seconds to automatically qualify for Tokyo.

A couple of weeks after his qualifying run Browning raced again in Sydney, where every millisecond of his race was recorded by a radar pointed down his lane. He ran a very solid 10.09 in fairly atrocious conditions. At around 30m into the race he hit a maximum velocity of 12m/s – an incredible 43.2km/h. Apart from Usain Bolt, it’s about as fast as anyone has run. “I know I’ve got the motor,” he says. He knows that if he can keep that velocity up for long enough he can win. “I may be a pragmatist, but I am also a huge dreamer,” he says. “You have to think that you can become the best in the world.”

And so Rohan Browning is putting those unknowns to work for him. Sure, some of his competitors abroad have run sub 10 seconds, but not on a chilly night in Brisbane at the absurd time of 9pm. And still he was a mere half a metre from breaking the magical 10 seconds. “If I run the best I can possibly run, I’m in with a chance,” he says. “The hardest progression will be to the finals. It’s a brutal process, but once you are in there there’s three out of eight guys going home with a medal – I’ve got mates who’d punt on significantly worse odds than that.”

He has yet to reach his peak. He will be coming into his prime at the next two Olympics in Paris and then in Los Angeles. He reckons he could even aim for a swan song at Brisbane in 2032, when he’ll be 34. He’s got ample incentive – he’s nearing the end of his long-drawn-out arts law degree at Sydney University. “The longer I can run fast, the longer I can put off becoming a lawyer,” he says. “It keeps me motivated.”

For 21-year-old BMX racer Saya Sakakibara, the uncertainties surrounding the Olympics seem trivial compared with the past 18 months of her life. Sakakibara first started riding BMX after watching her older brother Kai tearing around the track. With a Japanese mum and a British father, she grew up between Japan and the Gold Coast. The constant was racing and training with her brother. They were the king and the queen of Australian BMX racing and they dreamt of competing in their old home town of Tokyo together. And then that dream was shattered.

In February last year Kai was racing in an Olympic qualifying event at Bathurst when he was involved in a sickening crash. His head was slammed into the track as he rounded a bend. Kai was airlifted to an intensive care unit in Canberra with a severe brain injury. He was in a coma for eight weeks. “It was really scary,” his sister says. “The doctors didn’t know if he’d make it through.” His recovery since has been slow and determined. Driven by a desire to be in Tokyo for the both of them, Sakakibara jumped back on her bike almost straight after the accident. “It’s been really, really hard,” she says. “We were training partners. Brother and sister. We had this dream for so long that we’d be at the Olympics together and to have that taken away has taken a lot of adjustment and I feel like I am still adjusting.”

One of those adjustments has been to focus onthe Olympics for herself, rather than for both of them. “I found that feeling to be quite strong at the start, that I was doing it for him,” she says. “As I went along I found I had rethink it. I had to do it for myself, with inspiration from Kai, rather than for Kai – if that makes any sense.” Doing it for Kai felt like a burden. Focusing on herself seemed to lighten the load. “I’m fully focused on improving myself and being the best that I can – if I approach it in this way it’s not a chore.”

And so the postponement of the games has been somewhat a blessing for her – it gave her time to recompose herself after her brother’s accident. This is her first Olympics but these Covid Games will be so strange that it will be new, she says, even for experienced campaigners. It should flatten the field for everyone.

BMX is a power sport, a mad scramble around a track with jumps and turns where eight riders are competing. It grew out of motocross racing, invented by kids who couldn’t afford motorbikes. The races may only last for 45 seconds. “The biggest thing is definitely the start,” Sakakibara explains. “The race is almost decided in the first two seconds.” And so she’s been heavily focused on her start technique and preparations have been going well. In 2019 she came seventh in the World Championships, but she’s improved since then and is seen as a real medal hope. “I know that I have improved but there’s no doubt that other riders have also,” she says. “There’s no way of knowing until we get out there and race… I’ve done everything I possibly could to prepare and so I am going to go over there and just enjoy it.”

Back in BC, before Covid, Kelsey-Lee Barber travelled to Doha to compete in the World Athletics Championships in the women’s javelin. It was October 2019, a few months before the pandemic hit. The event was a nail-biting affair with the lead see-sawing between the top competitors. The Chinese athlete Liu Shiying put in a magnificent 65.49m throw to take the lead. To win, Barber needed to pull out something special.

With one throw remaining, she took the advice of her coach and husband, Mike, and moved back to her long run up. She sprinted in fluently and released the spear in a graceful, powerful motion and an almighty grunt, pulling up a metre or so before the line. She watched, and watched… the spear wobbled and spun and hung in the air for an impossibly long time. And then it speared into the turf a metre or so further than the leading throw. Barber, 29, began jumping around like a delighted little girl. She was the champion of the world.

In Tokyo, Barber will be the one to beat. She’s the one other athletes have been thinking about, late at night, fantasising about how Covid may have affected her preparations and advantaged theirs. Athletes refer to this endless crunching of data in a fictitious attempt to predict an outcome as mathletics. In the world of javelin mathletics Barber’s throw in Doha will be the benchmark.

She admits that the uncertainty surrounding these Olympics has been unsettling. “There was just no map of how it was going to look,” she says. “You just had to be so fluid in your plans and your programming – you just couldn’t look too far ahead.” She’s glad now a date has been fixed. But she’s preparing herself to be flexible, to have a plan but to know things could all change at the last moment. The plan is to expect disruption.

Barber took up discus and javelin in high school in Victoria. She loves the combination of athleticism and technique – power and finesse. “To do well in javelin you’ve got to have the power and you’ve got to have the speed, but there is this really beautiful element of suppleness and technique… you have to have a feel for the javelin.” It is a thing of pure beauty when every ounce of energy created from the run and the throw are transferred into the spear – all these elements are in sync. “It’s hard to articulate these things, but you feel it.”

She has always been good at this event but it wasn’t until the Commonwealth Games in 2014 that she realised she could be one of the best. “That was my breakthrough year,” she says. “I gained a lot of self-belief in that year.” It resulted in her winning bronze and it sparked a fire within. “That success… I felt like I could go on with it and do something really special.”

The question she is often asked is how the coach/husband thing works. She says they are good communicators and insists it’s always a very professional relationship on the track. “Where the lines do get blurred a little is at home sometimes,” she says. “If the session didn’t go so well we may both simmer for a bit.” But, she says, having a coach who knows her so well is a huge advantage.

What she is trying to achieve is a state where her entire performance is more poetry than effort; that the throw happens so fluidly and efficiently that she’s not thinking about it at all. It’s as though her body is thinking for itself. “There’s a lot of work that goes into that, allowing yourself to be in that state… that state of peace.” If she can achieve this athletic state of grace in Tokyo she’ll have some gleaming bling to match the mood.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout