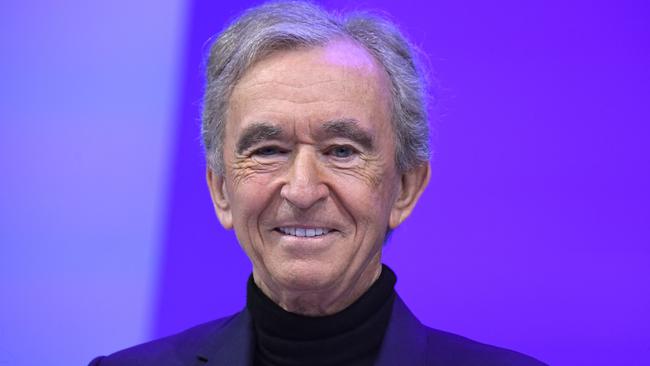

The new richest man on Earth

Bernard Arnault has surpassed Elon Musk on the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. The Louis Vuitton owner is a world apart from Musk’s publicity-courting, tech bro persona.

There are billionaires and then there are billionaires. There are the ones you have heard of – hear about, it is starting to feel like, every single day. I am talking about Elon Musk, of course. And then there are the ones you never hear about, unless theirs is an industry you are particularly interested in or, in my case, write about.

On Tuesday it was announced that a billionaire in the latter camp, Bernard Arnault, the chairman and CEO of the French luxury group LVMH, had overtaken Musk as the richest man in the world. LVMH encompasses 75 brands in total, including fashion heavy-hitters such as Louis Vuitton and Dior plus other varieties of poshness such as Moet & Chandon. Last year it grew its revenue by 44 per cent.

In the first nine months of this year revenues were up another 28 per cent.

Yes, you may be worrying about your heating bill this December, but the rich continue to get richer, and to buy up, by way of one example, the latest Christmas-appropriate gold-and-white iteration of Dior’s best-selling book tote, a snip at £2550.

To visit the vast and unbelievably lavish new Dior store on the Avenue Montaigne in Paris, which is almost as full of customers as it is product, is truly to step through the looking glass. If you can foot the bill to stay in the store’s en suite apartment – €25,000 a night, thank you very much – you will have four shop assistants at your beck and call throughout the night.

All of which goes some way to explaining why Arnault is now worth $171bn, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. Musk, the poor mite, now weighs in at a mere $164bn after a bump in the Tesla road erased $107bn off his fortune.

I have scoped out Arnault, 73, across countless runways over the years, flanked by assorted glamorous celebrities, not to mention his glamorous daughter, Delphine, Louis Vuitton’s director, and his glamorous second wife, Helene, a concert pianist. The piano, incidentally, is one of the few things at which Arnault himself has failed.

As a child he was good, yet not, ultimately, good enough. “I always liked being number one,” he told the Financial Times in 2019. “I did not succeed at the piano.”

His summary of the occasion when he, a keen tennis player, took on Roger Federer, is also telling. “Obviously I lost 6-0,” he recalled, “but I won a point.”

Can I tell you much else about him? No. Gnomic doesn’t begin to cover it. This is a man who, according to Nadege Forestier and Nazanine Ravai in The Taste of Luxury: Bernard Arnault and the Moet-Hennessy Louis Vuitton Story, even kept his first marriage a secret from the employees at the family-owned construction business he joined after his studies at the Ecole Polytechnique, favoured by the French elite. I have no idea what he has on his bedside table, but I will wager it won’t include cans of Diet Coke.

That Financial Times interview was as rare as a Louis Vuitton bag used to be before Arnault transformed the luxury business model and made said bags if not ubiquitous then certainly common. It is Arnault more than anyone else who is responsible for transforming the luxury model from that of small, family-run artisanal businesses – with the customer bases and profit levels to match – into mass market-targeting dream factories. In Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Lustre, Dana Thomas describes Arnault as a “luxury baron”.

“What I like is the idea of transforming creativity into profitability,” is how the businessman prefers to put it.

He started with Dior in 1984, which he cunningly picked up as part of the Boussac Saint-Freres textile empire, and which was in financial freefall at the time. The 35-year-old Arnault recruited a grand French investment bank called Lazard Freres to help him raise the $80m price, and to ensure the blessing of the government for the deal.

Over the next few years he sacked 8000 workers and divested himself of many of Boussac’s manufacturing assets, earning himself €500 million in the process.

Arnault had become one of the richest men in France, and in so doing he had challenged the way his country did business. “He was a new breed of French executive,” Thomas writes, “the sort who would exhibit the kind of ruthlessness common in America, where profit was the main if not only goal.”

Needless to say his approach made him enemies. It also earned him a nickname: the wolf in cashmere.

His genius was to streamline production at the same time as scaling it up. He also harnessed the power of advertising and, latterly, social media, and staged big, splashy catwalk events to feed into both. He saved money in some areas, in other words, but spent more in others.

Above all he understood that a status symbol is, as its name suggests, as much about what it represents as what it actually is. He set out to create product that, as he once told the Harvard Business Review, “fulfils a fantasy. It is so new and unique that you want to buy it. You feel you must buy it, in fact, or you won’t be in the moment. You will be left behind.” Louis Vuitton’s on-point collaborations with big-ticket artists such as Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami further fuelled the dream, not to mention the coffers.

Arnault’s cultural ambitions have been as vaunting as his commercial ones. His opening of the Frank Gehry-designed Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris in 2014 was an especially boldface move. Last year’s reincarnation of the defunct La Samaritaine, one of the city’s most iconic department stores, as the Cheval Blanc, an ultra-luxe hotel, was another.

You will probably be unsurprised to learn that culture and commerce tend to be intertwined in the world of Monsieur Arnault. One of his rare misfires was an attempt to buy Gucci in the 1990s. In the end it was his arch-rival Francois Pinault, owner of the luxury group Kering, who took control. When Pinault donated €100m for the rebuilding of Notre Dame three years ago, Arnault announced a contribution of €200m only hours later.

This year Arnault declared his intention to stay in his present role until he is 80, but that hasn’t stopped the industry gossip around his succession plan. All five of his children now work in the business. Will it be Delphine, at 47 the oldest, who gets the gig? The other favourite is Antoine, 45, who runs image and communications for the group, and is married to the model Natalia Vodianova. Then there are the three twentysomethings from his second marriage snapping at their heels. “They all have something of me,” he has said.

But he would not go any further. “It’s not for me to explain … the personalities of my children.”

Welcome to fashion’s take on Succession. Watch this space.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout