Texting makes me anxious, so I instead write love letters

For couples dating in the digital age, instant communication is a double-edged sword. Maybe love letters could be the antidote we’re looking for.

Living in an age of digital courtship is both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, the relaying of affection is resolved with immediate gratification. An “I miss you” text is met quickly with the assurance that the feeling is mutual; a call is answered in seconds, no matter where in the world either partner happens to be, to chat about the serious or inane, to share a joke, to feel less alone.

But the instantaneity of the phone has also thrust upon partners a certain responsibility: to respond as soon as the message goes through. The minute we hit send, our recipient is notified and expected to respond as quickly as possible. When they don’t, we panic. It’s a phenomenon that has been well-documented both scientifically and anecdotally. “Why hasn’t he texted me back?” is the singular defining question of my early-20s conversations with friends. So universal is the anxiety of a delayed reply that in recent years, it’s sparked a competition of sorts between lovers, a test of dominance to see who can outlast the other, and come off as less desperate.

“It’s been 30 minutes,” a friend said to me once about a classmate she’d been flirting with. “So when he replies, I’ll wait 30 minutes before responding.”

It was this bizarre 21st-century dance that I found myself in when entering into my own relationship, the culmination of giddy back-and-forth texting. The adrenaline-rush came with its inevitable lows. Over time, I became not only expectant of immediate replies, but fancied myself a linguistic psychoanalyst. Had I said something wrong? Why was he texting me one-word responses? Oh god, he’d used a full stop.

Everything, of course, was fine (nine times out of ten, he was just tired). But conditioned by the reality of instant communication, I catastrophised, and it affected my relationship. Digital romance made me anxious, Pavlov-ing me into checking my phone even when it didn’t buzz. Like so many of us, I had lost the ability to be completely alone with my thoughts. In desperate need of a cure, I consulted the internet. Some experts said to detox completely. Others recommended physical exercise, meditation or exposure to nature.

All I tried, and all worked to a degree. But none were quite so effective as writing love letters.

For two modes of communication, texting and letter writing could not be more different. A text is sharp, completed in shorthand and a litany of abbreviations. To text is to be an omniscient communicator. You know exactly when your message has been received and seen. Lingering on the screen long enough will reward you with the three undulating ellipses in a speech bubble, informing you that your partner is composing a response.

When you write a letter, you are blind to all but emotion. You sit alone at your desk, with a pen and a sheet of paper, bracing your body and clearing your mind. You ponder each word, rolling it around in your mouth to see if it tastes true. Spelling mistakes aren’t autocorrected, they’re left unnoticed or scribbled out, the remnants of an error, a reminder that you’re human. Letters are messy. Torn at the edges, creased and stained, epistolary exchanges bear the indelible marks of time. “I’m lying down on my bed,” I write in one. “I can see my neighbour cooking dinner through the window. The sky is orange, like a Dutch tulip.”

In a time where modern romance blossoms and withers under the gaze of technology, writing a letter feels radical. That there are so many more convenient, immediate ways I can communicate with my boyfriend makes my decision to write him a letter a pointed one. I capture my present on the page — an intimate thought, a fragment, a piece of myself. I send it into the aether and surrender to the unknown, not knowing when it will be opened, or if I’ll even get a reply. “There is a waiting — a forced patience — built into the mechanics,” novelist Jon McGregor writes. “In the time it takes for the letter to reach its destination, anything can happen: minds be changed, lives lost, loves discovered.”

It’s not just the uncertainty that is liberating — the physicality of a letter is also comforting. You can’t delete a phrase when the ink has taken hold. You don’t second-guess the sentiment. The realisation urges you to write only what feels genuine or meaningful, even if it might sound sappy or overly purple. So too does it demand care from the receiver. The rise of social media has decreased the average person’s attention span to just 8 seconds. On a mobile screen, engagement time amounts to as little as 1.7. A written letter though, like a printed book, necessitates concentration. It’s a singular focus that our phones — overflowing with information — have made almost impossible to find.

Don’t get me wrong, I still text constantly. I may be a romantic, but I’m not entirely impractical — you won’t catch me organising a dinner or a morning coffee through a letter. But when I’m feeling particularly vulnerable to currents of love, I resist sending a text and anxiously awaiting a response. Instead, I save it for a letter, or an in-person conversation.

Last year, my boyfriend spent three months studying abroad in Oxford. We called every second day, during his morning and my night-time. We texted just as often — I would send him a slew of thoughts, live-streaming my day, to which he would respond in turn when I was asleep. But every few weeks or so, I would sit down to pen a letter, telling him how I loved him in that particular moment.

The post office box was just down the road. I would yank down the handle and watch the letter drop into the black. It was a quiet affair. I never needed a reply.

-

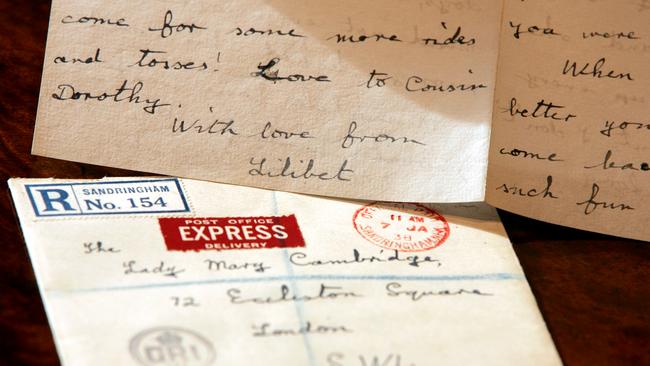

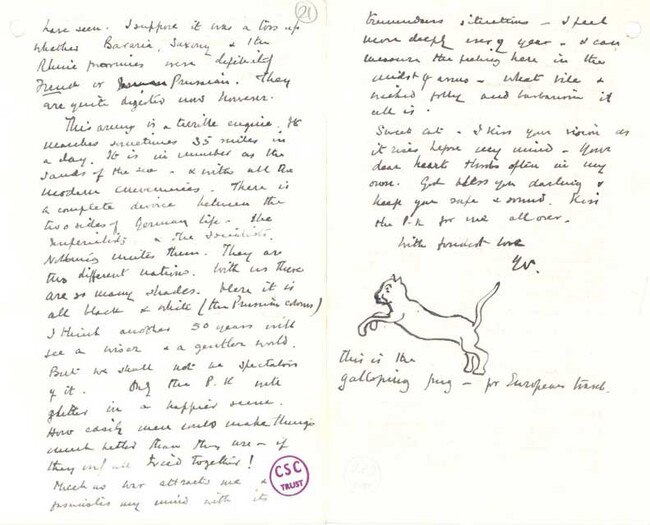

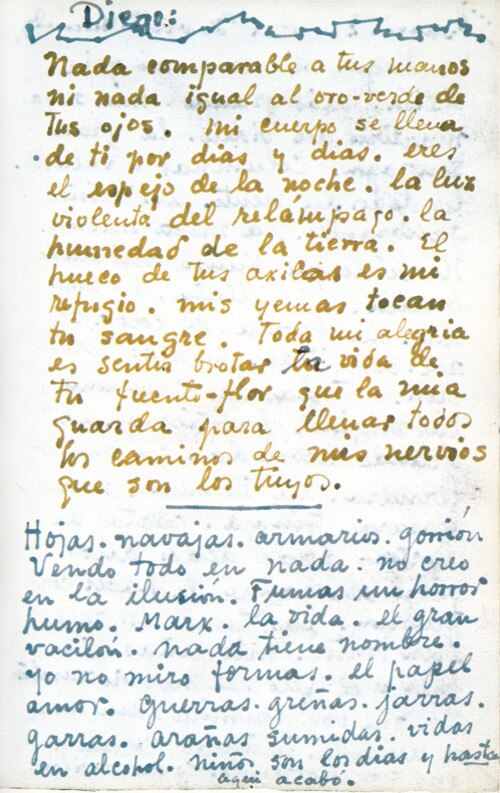

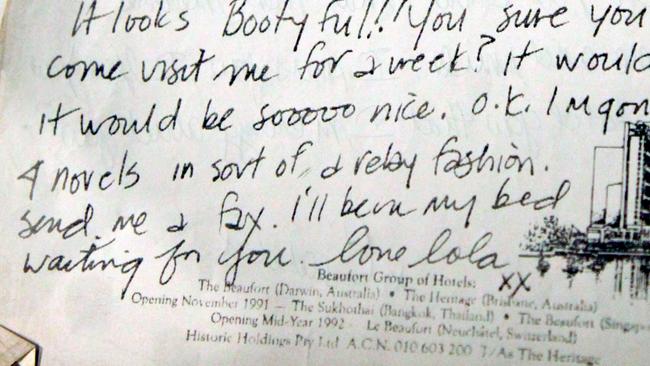

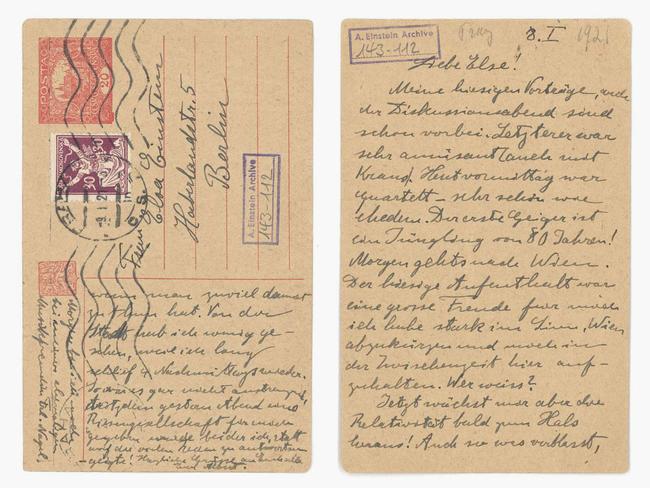

Thinking about writing a love letter? Let these epistolary exchanges inspire you

“Darling – I love these velvet nights. I’ve never been able to decide … whether I love you most in the eternal classic half-lights where it blends with day or in the full religious fanfare of midnight or perhaps in the lux of noon. Anyway, I love you most and you ’phoned me just because you phoned me tonight – I walked on those telephone wires for two hours after holding your love like a parasol to balance me.”

— Zelda Fitzgerald to F. Scott Fitzgerald

“My Own Boy, Your sonnet is quite lovely, and it is a marvel that those red-rose leaf lips of yours should be made no less for the madness of music and song than for the madness of kissing. Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry.”

— Oscar Wilde to Lord Alfred Douglas

“The other afternoon, when you fell asleep on my shoulder, I drifted off, too. But before I did, it occurred to me looking around at all of your things and your work and going through years of work in my mind, that of all your work, you are still your most beautiful. The most beautiful work of all.”

— Patti Smith to Robert Mapplethorpe

“My sweet love, I shall wait patiently till tomorrow before I see you, and in the mean time, if there is any need of such a thing, assure you by your Beauty, that whenever I have at any time written on a certain unpleasant subject, it has been with your welfare impress’d upon my mind.”

— John Keats to Fanny Brawne

“I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia. I composed a beautiful letter to you in the sleepless nightmare hours of the night, and it has all gone: I just miss you, in a quite simple desperate human way. You, with all your un-dumb letters, would never write so elementary phrase as that; perhaps you wouldn’t even feel it. And yet I believe you’ll be sensible of a little gap. But you’d clothe it in so exquisite a phrase that it would lose a little of its reality. Whereas with me it is quite stark: I miss you even more than I could have believed; and I was prepared to miss you a good deal. So this letter is just really a squeal of pain.”

— Vita Sackville West to Virginia Woolf

“A few days ago I thought I loved you; but since I last saw you I feel I love you a thousand times more. All the time I have known you, I adore you more each day; that just shows how wrong was La Bruyére’s maxim that love comes all at once. Everything in nature has its own life and different stages of growth. I beg you, let me see some of your faults: be less beautiful, less graceful, less kind, less good …”

— Napoleon Bonaparte to Joséphine Bonaparte

“Try to understand me: I love you while paying attention to external things. At Toulouse I simply loved you. Tonight I love you on a spring evening. I love you with the window open. You are mine, and things are mine, and my love alters the things around me and the things around me alter my love.”

— Jean-Paul Sartre to Simone de Beauvoir

“I already love in you your beauty, but I am only beginning to love in you that which is eternal and ever previous – your heat, your soul. Beauty one could get to know and fall in love with in one hour and cease to love it as speedily; but the soul one must learn to know. Believe me, nothing on earth is given without labour, even love, the most beautiful and natural of feelings.”

— Leo Tolstoy to Valeria Arsenev