Tiny window into the life of a desperate girl

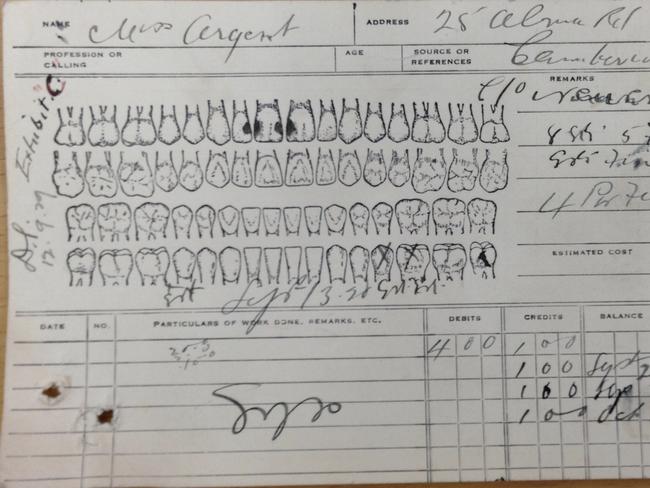

Dental records helped identify the body of Irene Argent, 18, who died after a botched abortion in 1929.

The tooth is a right lateral incisor, from a lower jaw, with an amalgam filling. Glenferrie dentist Ewin Orchard did not hesitate when police showed it to him in August 1929.

“The work was done by me,” he said. “I know my work.” When he produced a patient card, he resolved one mystery; another has remained.

Eighteen-year-old Irene Mavis Lillian Argent, Orchard explained, had kept no fewer than nine appointments between September 1928 and February 1929, for an extensive succession of fillings and extractions. He had not seen her lately; nobody had.

The 230,000 inquests at the Public Record Office of Victoria are the rawest of social history. How we die explains a great deal about how we live. Deaths resulting from botched illegal abortions testify to the past’s brutal social and sexual taboos: Irene’s is one of hundreds in the 1920s alone, representative and unique.

Her remains were found underneath hessian by a rabbit trapper at the corner of two unmade roads in Langwarrin at 4.30pm on August 18, 1929. Unwrapping a Gibsonia blanket secured by safety pins, he saw a human foot. There was not much else left.

The extent of decomposition suggested septicaemia, but the government pathologist could do no better than identify the remains as those of a woman of about 160cm in height.

There were, however, teeth in a distinctive overlapping jaw. The public revelation of a body flushed out a Hawthorn landlady, Gertrude Ryan, whose boarder had disappeared two months earlier bearing only a small suitcase. Armed with the dentition, two detectives, Percy Lambrell and James Mackerral, visited every local dentist until they found Orchard.

In the meantime, Ryan had received a letter from one Frederick Olney, a Tallangatta baker, disturbed not to have heard from Irene.

Olney had befriended her after she left the family farm in Traralgon the previous year looking for “a position” — in other words, work as a domestic servant.

Irene impressed as a simple, wholesome girl. She had won an elementary school temperance prize, taught at a Traralgon Sunday school, patronised Melbourne’s Young Women’s Christian Association and worked diligently for a Hawthorn mistress.

Others saw her differently. A Doncaster orchardist, Bill Johns, courted her haltingly then judged her severely: “I was rather doubtful of her; I thought her affections were a bit divided. I became suspicious … In consequence, I found I lost faith in her, to a certain extent.”

Olney confirmed that Irene had “gone out with different men”, and reported “that her monthly periods had stopped”.

Irene believed she was pregnant to a 25-year-old railways porter, Edgar Uren. When an abortifacient had proved ineffective, she had considered other options.

Olney recalled saying: “It must be a great worry on your mind. Look at the disgrace it would be if you have to go through it.”

He continued: “I told her she ought to get Uren to marry her. She said she would try and see what he said about it. Later, she said Uren had told her he was not in the position to marry her as he had no money. I said: ‘If you want any money I will lend it to you, I will not see you stuck’.”

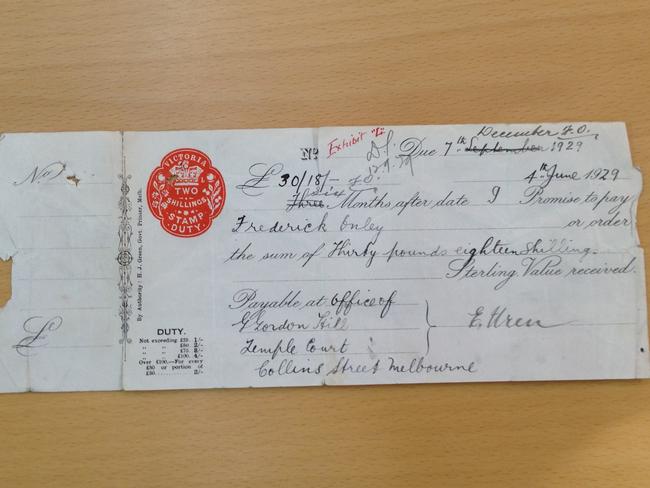

When Irene began talking of “getting fixed up”, Olney cautioned her: “If she went under an illegal operation, she could lose her life.” What he agreed to do, nonetheless, was lend £30 to Uren: “If you say you can get the girl fixed up without any risk, you can have a loan, but I will not be mixed up in it myself.”

Uren testified that he had turned to a knowing older colleague at Flinders Street railway station, Thomas Draper.

“I told him that I had got a girl into trouble and asked him if he knew of anyone that could fix her up,” he said.

Draper, he said, organised for her to be collected from an agreed location in Dandenong Road at 7pm on June 4, 1929.

There, however, the trail went dead. “It is bloody lies,” said Draper, when Uren’s remarks were put to him. “Some months ago, Uren told me he had got a girl into trouble, and if I knew where I could get her fixed up. I told him I did know of a place, but that I had forgotten the name …

“My memory is not good … When Uren states here in his statement and on oath that I said I was going to meet another man, I do not know why he should say that.”

And that was all it took for police to drop the matter, and for even the Truth newspaper to veil “the terrible death of the little country Sunday school teacher who came to Melbourne and forgot to practise that morality she had taught to others”.

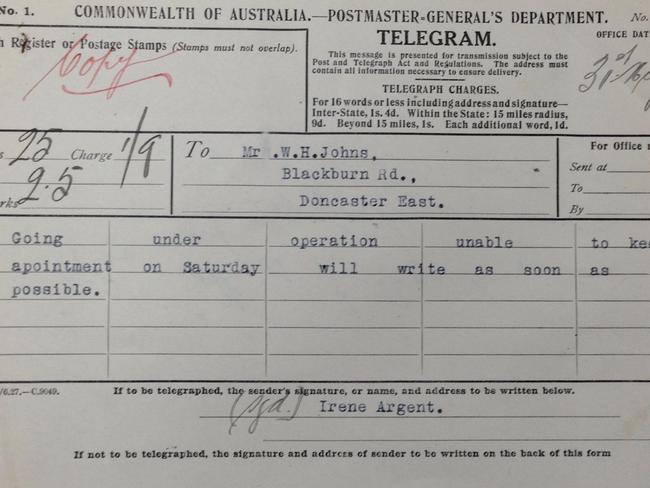

Because the coroner recorded an open verdict, Irene did not even count as a victim of illegal termination. What survives of Irene is a file at the Public Record Office with her faded photograph, some letters in a shaky hand, and the telegram she sent Bill Johns breaking their last engagement, forestalling her fear, dread, shame and confusion with a businesslike tone: “Going under operation unable to keep appointment on Saturday will write as soon as possible.” And an envelope — of teeth.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout