‘Think on me’: Convict love tokens tell a new story

Marooned in the UK, convict love tokens eluded the attention of local historians. Now they are seen as the original white Australian artwork.

Thomas Burbury is a distinguished early Tasmanian: a city councillor and substantial landowner who on his death in July 1870 was reported by The Mercury to have “commanded the esteem and respect of his fellow men” by conduct that “always secured public confidence”. His descendants included a Chief Justice who became the state’s first Tasmanian-born governor. Yet by this time, a century and a half on from his arrival, it was forgotten or obscured that Thomas had been one of 160,000 souls to arrive in the antipodes in chains.

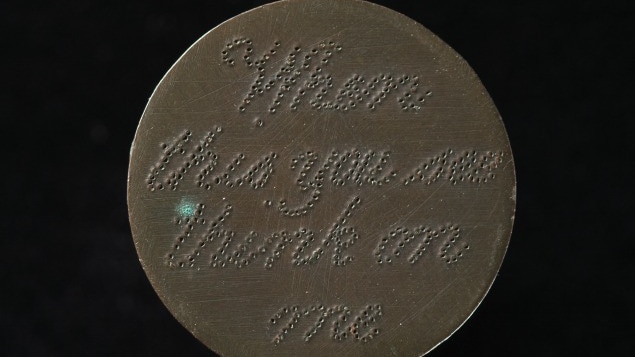

This, Burbury’s convict love token, is both an unprepossessing relic of a forgotten story and a sample of a forgotten folk art. In Australian Jewellery (1992), Anne Schofield describes convict love tokens as the original white Australian artwork. Examples date back to the First Fleet. They were, as the name suggests, created as keepsakes for those a convict was leaving behind. The usual medium for engraving or stippling a message was a so-called “cartwheel penny” — a 1oz copper coin in common circulation, soft enough for repurposing, big enough at 36mm to carry a sentimental image or snatch of doggerel. Marooned in the UK, they had rather eluded the attention of Australian historians and curators. But about 40 years ago, they caught the fancy of Tim Millett, a young coin and medal dealer working at a family-run numismatic firm.

“To be honest I was never terribly good at the minutiae of numismatics,” he says. “I always preferred the social history side of our world and I started finding engraved coins at work in old lots and in auction lots. About 1980 these were classified largely as rubbish which was excellent for me.”

Two of Millett’s earliest acquisitions were tokens left behind by 23-year-old Burbury and 19-year-old Thomas Sparks.

Burbury and Sparks were not your standard unlucky souls sentenced for stealing a loaf of bread. They were Luddites, involved in what George Rude’s classic Protest and Punishment (1978) calls England’s “last major incident of industrial machine breaking”, when workers outraged by reduced piece rates set fire to a mill quipped with automated silk looms in November 1831. Hapless owner Josiah Beck was paraded through the streets of Coventry facing backwards on a donkey, then thrown in a mill dam. Burbury and Sparks, identified as insurrectionaries, were sentenced to hang. The evidence against Burbury in particular was ambiguous if not contradictory; public sympathy was considerable. So much so that local MP Edward Ellice joined a successful campaign for commutation of the sentences. Ellice was then a prime mover in the Reform Act, a watershed in Anglo democracy. The prisoners’ love tokens, which seem to have been executed by the same hand, reference their sensations of martyrdom. Both complain of being “Condemned 24 March 1832”. Sparks’ features a Forget Me Not, its addressee uncertain. Burbury, who was leaving a wife and infant daughter, asked: “When This You See/Think on Me.” From here on, however, the co-accused took sharply divergent paths. Sparks, sent to Sydney, disappeared into obscurity; Burbury, officially listed as sharp-nosed, large-chinned, red-whiskered and 170cm, solidified into respectability. The public campaign in Coventry bore further fruit when Burbury’s family was allowed to follow him to Hobart in November 1832. By the time they arrived, Burbury had been assigned to a successful pastoralist, Thomas Anstey, for whom he would do yeoman work as a shepherd, tangling with bushrangers and sheep stealers alike, blending so successfully into civil society that he won his ticket of leave barely six years after being under sentence of death. His story attests the scope transportation offered for successful reinvention. In 1998, Millett’s collection made its first appearance in Australia, in an exhibition; 10 years later, now featuring more than 300 items, it was acquired by the National Museum. In the meantime, however, Millett had come across something unique: a second identical Burbury token. Maybe there were several; it’s possible there were many. The implication, then, is that the token was not of love but of political grievance, that it was not only his wife he wished to “think on him” but sympathisers with his cause. We don’t know. To his grave 150 years ago, Burbury took some secrets that have remained irrecoverable.

Every object tells a story. Each Object Lesson column takes a commonplace object encountered in Gideon Haigh’s travels, and draws from it an otherwise hidden tale.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout