Obituary: Peter Weiss and the fashionable art of giving

He loved great conductors and playing cello, but Peter Weiss was always destined to be a maestro of style.

When Peter Weiss was eight years old he saw a cello at his doctor’s house and decided there and then it was the instrument for him.

He studied at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, played with the Australian Youth Orchestra and took himself to Europe for further study. He adored the instrument’s rich, mellow sound — “It gives me a sense of being,” he said much later in life — but he said that taking up the cello was also about showing off.

He realised, when he was playing with the youth orchestra, that he never wanted to be in the second rank of players. He had to be the best. When he left for Europe the day after his 21st birthday, he went to the Salzburg Festival and fell under the spell of the reigning maestro, Herbert von Karajan. As he watched Karajan in action on the concert podium, and driving around in his Porsche, some of that glamorous allure must have rubbed off on the young Peter. His children later would say that he should have been a conductor.

Weiss made his name as the co-founder, with his first wife Adele, of one of the most recognised brands in Australian fashion. But he would abandon the fashion design business with the same decisiveness, permanent and irreversible, with which he quit his cello studies when he was in his early 20s. He would never be good enough to become the star cello soloist that he perhaps had in mind. And he was never proud of being in the rag trade, he said, even as he ruled his empire and cut deals like a maestro of the business world.

Weiss was born in Vienna, the second son of Fritz and Alice Weiss. They fled the city in 1938 — the year of the Anschluss with Nazi Germany — and arrived in Sydney the next year, lodging in a rooming house in the eastern suburbs. The Weisses would lose much of the remainder of their family in the Holocaust.

Growing up in a European family, culture was key, and in particular a love of music that would continue throughout Weiss’s life. With his father he attended the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s concerts at the Town Hall, during the era of international guest conductors such as Otto Klemperer, John Barbirolli and Eugene Ormandy. They would greet other emigres at the hall and Peter would recall the smell of mothballs when they brought their European winter coats out of storage.

He began working in the rag trade, first selling shirts and trousers at Mallory Menswear in Darlinghurst Road, and alongside his father in his apron business. He quickly learned the art of the upsell — “You don’t sell one item, you sell two,” he said — and of bringing some European fashion sense to 1960s Sydney.

In a 1977 interview, Weiss recalled returning from a trip to Europe “with some great gear I picked up in St Tropez and places like that. I gave up the cello, we made up a small collection and sold it to Mona Crawford at Mark Foy’s. We called them Camp Cove Casuals after the beach in Sydney.” Weiss then expanded from aprons into budget dresses. “Mass production, something like a sausage factory — that’s how it was after the war.”

With Adele he started a mail-order business selling DIY fashion kits through The Australian Women’s Weekly. The pair would set up their own company in 1973, launching the Weiss label two years later, when Peter was 40. It began in a studio in Sydney’s Surry Hills — the epicentre of the rag trade at the time — with two sewing machines and an overlocker. Adele headed up the design team, while Peter looked after the business side. He was also a master marketer. As he said in that interview two years later: “We knew exactly what we wanted to do. It’s really a total concept of dressing — from day into evening.”

This was a time when Australian-grown fashion labels were still looking to Europe for inspiration, and the seeds of the local industry were still being sown. The couple soon would reap the rewards.

Their success started with a thriving separates business, and they would eventually have more than 40 stores and concessions.

Nancy Pilcher, the editor-in-chief of Vogue Australia for eight years from 1989 and a close friend, recalls Weiss as being, “larger than life” and “unique in his approach to excellence”, with a love of life that was contagious.

“Peter was the backbone of the halcyon days of fashion in Australia. Their collections were beautiful,” Pilcher tells The Australian, adding that she still has pieces in her wardrobe.

“Fashion was more to him than clothes on a rack, he possessed a way to encompass personalities and make the fashion come alive.”

Pilcher says Weiss’s legacy for the Australian fashion industry was similarly broad.

“He always had time to devote to mentoring, he touched so many lives in a way that will leave a lasting legacy,” she says.

Model and entrepreneur Maggie Tabberer recalls Weiss had “very good smarts” as a businessman. She would produce the fashion shows for the brand that she says included Weiss’s inherent understanding of showmanship.

“He always raised the bar, enough was never good enough for Pete,” she says. One show had been switched to a university to accommodate more people. “It was a really big, ugly, cold room and I said to him, ‘What are we going to do about this room? It’s terrible.’ He said, ‘leave it to me.’ The next thing a truck arrives and these guys are carrying in eight-foot-high pine trees in buckets. And he placed them all around the room to cover it up.

“Another time, he hired an army band and they arrived out the front of Sydney Town Hall and came up the stairs in the room and everyone stood on their chairs and screamed with excitement. He just knew that you can’t put a value on exciting people.”

The Weisses would pioneer the contemporary corporate uniform in Australia, starting with Ansett in 1981. Of the airline uniform, a newspaper report at the time said: “The days of the sex-symbol air hostess are over. She has been replaced by a ladylike, businesslike image more suited to the 80s.” Westpac would follow two years later, with Weiss reportedly shaving off his signature stubble to present to the Westpac board.

An ad campaign in the 80s would kickstart another money-spinner for the brand. Weiss Art began with the Weiss logo, simply the name in black brushstrokes on white. Sensing an opportunity, artists were commissioned to depict a range of Australian symbols. from animals to the Sydney Opera House, rendered in similar, simple fashion. “What colour was to Ken Done, black and white was to Weiss Art,” says publicist and close friend Adam Worling. Tourists in particular lapped them up on everything from mugs to sweatshirts.

Another opportunity arose when Weiss started importing Pringle knitwear from Scotland but added his own name to make it Weiss Pringle - without the permission of the Scottish originators. “We ended up having about 24 concept stores called Weiss in David Jones. We became the biggest individual purchaser of Pringle knitwear outside Scotland,” Weiss said in 2013.

After 30 years of marriage and two children, Ariane and Antony, Peter and Adele split in the early 90s. The love for the business was also on the rocks. Despite a turnover of $10m in 1994, Weiss started to wind up the business soon thereafter, with David Jones taking over Weiss Pringle in 1997. Despite leaving the fashion industry behind, Weiss’s flair for business and sales was still intact.

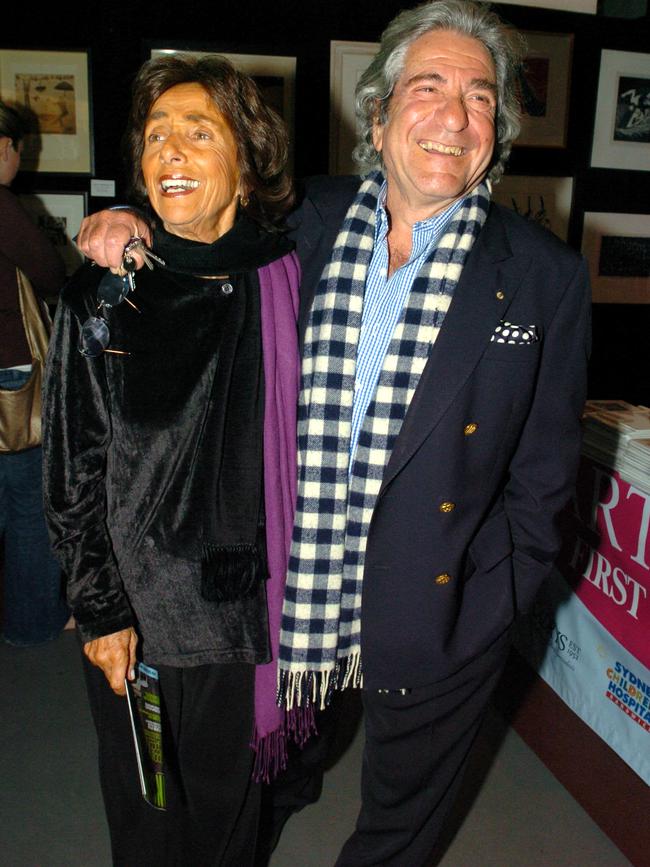

Moving to Sydney’s Palm Beach, he set up a homewares shop nearby for a few years, causing locals to dub him the Merchant of Avalon. It was in his new area that he would meet the woman who became his second wife, Doris, who was born in the same hospital in Vienna as Weiss, and in the same year.

As Weiss wound down his fashion business his interest in music returned. With the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s former managing director, Mary Vallentine, he started the Music for Spring concerts on Sunday afternoons at St James’, King Street, hosting drinks afterwards in the crypt. A long-term supporter of the SSO, he founded the Maestro Circle in 2008 to help raise funds for orchestra recordings, tours and other projects.

The Art Gallery of NSW was a big part of Weiss’s life. In the 80s he was an early donor to the gallery foundation and for a time sat on its board, although committee meetings weren’t his style. In 2017 he gave the gallery Michael Parekowhai’s sculpture of Captain Cook, The English Channel.

He led the campaign for the Opera House to buy a tapestry, Les Des Sont Jetes (The Dice are Cast), that was designed by Le Corbusier after a commission from Joern Utzon. Later he gave $1m towards the upgrade of rehearsal rooms in the Concert Hall.

“The fact that he was a donor was only a very small part of my relationship with him,” Sydney Opera House chief executive Louise Herron says. “He was an incredible philanthropist … it was his sensibility and his complete recognition of the importance of expressing our souls and our spirits, principally through music.”

She says she will discuss with the SSO and the Australian Chamber Orchestra the possibility of a musical tribute to Weiss at the Opera House when the venue reopens.

The orchestra also has benefited. Weiss gave $1m towards the ACO’s purchase of a Stradivarius violin, and in 2016 he donated a $1.8m Guarneri cello that had been on loan to the orchestra.

In 2015 he bought the former home of composer Peter Sculthorpe and had its music studio lovingly restored, with the hope of hosting intimate concerts and visiting artists there.

Earlier this year, Weiss, who suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, gave $4m to the University of Sydney for research into the disease.

Weiss maintained that he wasn’t among the mega-rich and that his generosity was motivated by things he cared deeply about.

He didn’t regard it as philanthropy; more as a natural progression of a life he knew was nearing its end. When he gave the Guarneri cello to the ACO for Timo-Veikko Valve to play, he justified the decision in the simplest of terms: “It’s where it belongs. It doesn’t belong to me. I happened to own it, but it belongs there.”

Weiss died at home last weekend. He is survived by Doris and children Ariane and Antony.