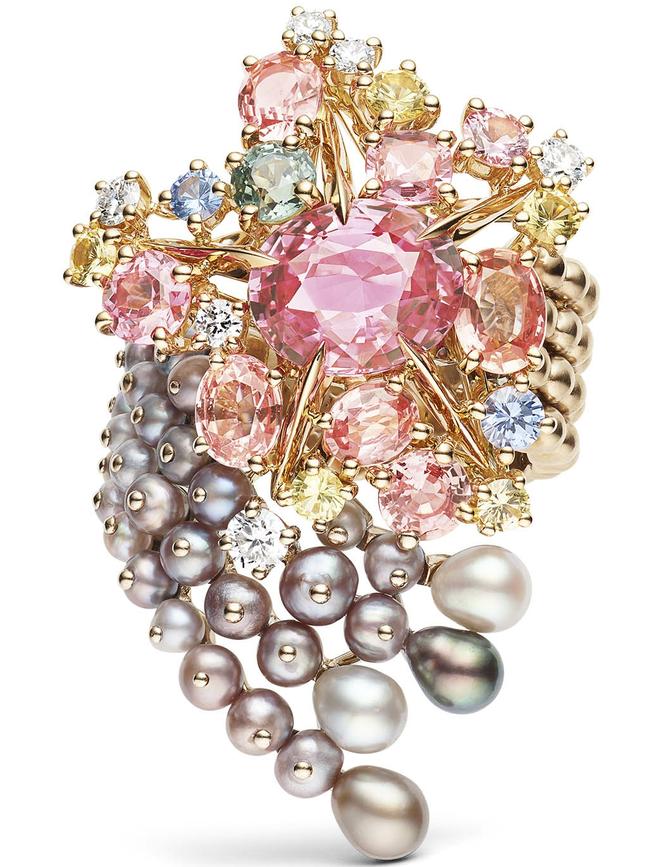

Chaumet’s high jewellery collection Ondes et Merveilles

With a heritage that includes Napoleon and his empress, Josephine, French jeweller Chaumet has no need to invent its own story.

For such a storied maison, French jeweller Chaumet is not so interested in storytelling. Or at least not stories of the made-up kind. As CEO Jean-Marc Mansvelt says, there’s no need.

“At Chaumet, we don’t do storytelling,” he says. “We don’t need to invent something. It’s already all there – the connection to nature at a pure form, the story of Napoleon and Empress Josephine. Our challenge is more, how do we choose what we are going to show, what we’re going to say, rather than inventing … How do you continue the line? At the same time, how do you do the thing so that it’s relevant to people today? That’s really the challenge.”

-

Explore the Watch and Jewellery special edition of WISH, available online and in print on Friday, 18 November.

-

The first Parisian jeweller to open on the Place Vendôme in Paris, Chaumet began its real story in 1780. It was founded by Marie-Étienne Nitot, who described himself as a “jeweller-naturalist’’ to capture his passion for plants. Joseph Chaumet joined in 1895, and gave the maison its name. The client list includes, of course, the maison’s eternal muse, Empress Josephine, the first wife of Emperor Napoleon I (who also commissioned Chaumet to make his Coronation sword). Josephine was a keen, and competitive, botanist, adding plants and species from far and wide to her Malmaison garden. Then there’s everyone from the glamorous Edwina, countess Mountbatten of Burma and the last Vicereine of India, to movie stars such as Natalie Portman and Diane Kruger.

A tour of one the maison’s archive rooms, newly renovated along with its Place Vendôme flagship, was an opportunity to peek at a record book and note one Madame Picasso putting in her orders.

The archive rooms are, as heritage director Claire Gannet says, “dedicated to our treasure”. Of which there is a great deal.

Indeed, this heritage, the maison’s entwinement with French history, could surely be overwhelming. Mansvelt says that for a lark, the archival team worked out that if you lined up all of the documents in the archives, which include some 66,000 drawings, 300,000 prints and much more, they would stretch 1.5 times the perimeter of Place Vendôme.

Balancing this with new ideas, new ways of expressing Chaumet’s enduring story, is an eternal challenge for Mansvelt.

“I think that is what is important for me, is to identify what really are the characteristics, fundamentally,” he says. “Whatever the period of Chaumet, there are a certain number of characteristics. From that, you reinterpret, you look around you, you just look, you read magazines, you look to the social networks, you walk in the streets, and [mimics looking up from a phone] eyes open.”

Mansvelt notes that people wear their jewellery differently now compared with some 200 years ago; they certainly have different lives. This has implications for technique. For example, the Carnation tiara, created around 1908 and featuring enormous diamonds on tiny pieces of metal. Making something like that today, he says, would not be possible.

“The style, the handwriting of Chaumet – how do you interpret it again today? So yes, there is a challenge, a difficulty in the drawing, as well as in the execution,” he says.

The jewellery workshop, led by workshop director Benoît Verhulle and creative director Ehssan Moazen, who joined Chaumet in March 2020 following a five-year stint at Tiffany & Co. in New York, is always open to ideas, however. This might include new techniques and materials, and the use of technology for calculations and modelling. That said, new approaches can also come from looking to the past.

“From time to time, a miracle – we discover an old piece of Chaumet that suddenly reappears on the market. [It] doesn’t happen often, but it happens sometimes – either the client is bringing it back for a little bit of polishing or to ask the patrimoine if it’s ‘really a Chaumet’, as they say in the legend of the family,” says Mansvelt. “Then … suddenly it’s in the hand of Benoît and he’s like a child rediscovering something that has been done 100 or 150 years ago. Where suddenly he may discover a way of setting or a way of doing a little small detail.”

Mansvelt has two questions he asks the workshop and himself regularly. Will the maison’s predecessors see their work as making sense in respect of what has been done? And the same question, but for the future: will successors see this and think the same? It’s similar for Claire Gannet and the heritage team: the job is not only to preserve and conserve; it isn’t only the detective work of sourcing pieces and curation, but also to think about the Chaumet of the future.

“We [have] a strong priority to build archives from today. It’s not archives today but it will be come tomorrow,” she says, adding that deciding this is a collaboration between her team and other parts of the business, including the press, creation studio, events and retail divisions.

“What was the high jewellery creation, what was the set-up of the showcase, how [did] the shop look … that’s very useful in order to make research for tomorrow,” she says.

It’s interesting too that the tiara, one of the maison’s best-known emblems, worn by women of note and royalty throughout its history, remains as relevant as ever. As Mansvelt notes, “The absolute record in terms of sales of tiaras is 2021.” Perhaps the antithesis of confinement, tiaras, Mansvelt says, are now are mainly worn by brides on their wedding day and then kept in the family until the next wedding.

“The first reason is really about weddings,” he says. “Typically, either one person could buy for herself or the husband for his wife. Most of the cases are really parents for the daughter as a sign of transmission and tradition. Probably [they think] that the wedding is already beautiful, but it’s slightly even more if suddenly it’s connected to the story [of] Napoleon and Josephine.”

Some 264 maillechorts or metal versions of tiaras created throughout the maison’s 240-plus year history line the walls of Chaumet’s salons in Paris. There are two tiaras in its new high jewellery collection, Ondes et Merveilles (Waves and Wonders), a 69-piece ode to the ocean, unveiled during Haute Couture week in July. One proved so vexing to the workshop it was only completed two days before the presentation. It sold before the presentation opened.

“They had two real difficulties,” says Mansvelt. “The first one was really for both the jeweller and the designer to agree on how to express the movement, this idea of waves, but also this idea of the air, of the sirene [sirens] coming out of the sea.” The tiara features diamonds set in a new technique that mimics the scales of a mermaid’s tale.

It’s the first time Chaumet has devoted an entire collection to the ocean. Though if you look carefully around the salons on Place Vendôme there are odes to the building’s owner, Baron Baudard de Saint-James, treasurer general of the Navy under Louis XVI. Crabs, sails and anchors can be spied in the mouldings.

However water, in waterfalls, droplets, stalactites and more, has been a constant motif. Partly because, as Mansvelt says, water so perfectly captures the sense of nature in motion that Chaumet prizes.

“The question of water, the question of movement, the question of capturing the moment on something that is still … is typically the Chaumet style,” he says.

For a maison built on capturing nature in motion, it makes a lot of sense. As Claire Gannet, who made all manner of fascinating discoveries in her research for this collection, including references to the ocean dating from the company’s beginnings, says: “Water is the beginning of life.”

Part of Gannet’s role and that of her team is to decide what, and how, to exhibit Chaumet’s heritage. A recent example is the Chaumet Vegetal exhibition, staged from June to September this year, at L’École de la Beauté in Paris. Curated by an actual botanist, Marc Jeanson, the botanical director of the Jardin Majorelle in Marrakech, Morocco, it showcased the house’s long connection to all things botanical, as well as other fascinating pieces such as cyanotypes of algae made in 1843 by Anna Atkins and paintings of water lilies by Monet.

Gannet says the Chaumet style is “not a fairytale way of interpreting” say an oak leaf, or a sheaf of wheat, or as in Ondes et Merveilles, a piece of coral and the undulation of a wave.

“The way of treating nature in Chaumet is unique. Of course, nature is a source of inspiration for every jewellery brand, but in Chaumet we are very botanical … we don’t show that nature is good or bad, it’s as it is. [Our] creations are very realistic.”

Chaumet may reinterpret its key themes and motifs, but there is one rule, says Mansvelt: “We never do the same thing.”

Ondes et Merveilles is broken into chapters. They include À Fleur d’Eau, with articulated pieces, some of them transformable, that overlay marquise diamonds to create a sense of waves lapping. Gulfstream takes inspiration from the warm current that flows from Florida and is beautifully expressed in a 26-carat mint-green Colombian opal (this stone took two years to source) and Madagascar sapphire necklace. Another necklace in this chapter features a rare black 19.84 carat Australian opal. Throughout are ideas of starfish and pearls (in exquisite hues of olive, grey and mauve) caught in a fishing net, or the tail of a fish flitting around coral. In the Sous le Soleil chapter, an Art Deco inspired sautoir pendant with raspberry rubellites, tangerine garnets and splices of pink chalcedony discs evokes an umbrella on a dazzlingly hot day, while textured goldsmithing work in the Galets d’Or pieces take one to the seashore.

Particularly charming are the Encres brooches, their playfulness belying hours of work. Reminiscent of a sailor’s tattoos, the brooches, which can also be worn as a pendant, feature Grand Feu enamel work and are engraved with messages such as L’amour est une aventure (Love is an adventure). The brooches are a favourite for Mansvelt too. “It seems to be something like a sort of humour … But at the end, humour is mixed with the absolute virtuosity of the maison.”

He loves the À Fleur d’Eau diamond necklace because it answers the puzzle of high jewellery: the ultimate expression of art and craftsmanship, but not fully realised or alive until someone wears it.

“I think it’s expressed very well what I love and what I really push for Chaumet, a certain sense of simplicity, a certain sense of capturing the moment, like photography. It looks completely still, but at the same time it seems to be in movement,” he says. “For me, that’s very Chaumet, this feeling even before the start of the photography from the origin, the fact that they could capture the moment. Plus the fact that … jewellery has to be like a sculpture, a beautiful piece to look at on the bust of something, but the purpose of jewellery is not to be a sculpture, it’s to be worn.”

-

“Jewellery has to be like a sculpture, a beautiful piece to look at on the bust of something, but the purpose of jewellery is not to be a sculpture, it’s to be worn.”

-

Because of the global pandemic, the collection took longer than usual to create – four or so years compared to the usual two. This doesn’t include the time it can take to source, and wait for, the right stones.

Time is something Mansvelt values. Where is the value, where is the desire, he asks, if you can always get anything you want, whenever you fancy? “I think [time, waiting] is part of the dream. I think it’s part of luxury.” He says people are appreciating this notion particularly when it comes to high jewellery. Not only that it takes months of work to create the pieces, but jewellery is not just a fine and forever investment, but an art form, too. “People understand that high jewellery, particularly, is a real discipline of artistic creations. It’s not anymore … considered a minor thing,” he says.

Australia, meanwhile, will not have to wait too much longer for the opening of what Mansvelt calls a “real, true flagship” – in Sydney in the fourth quarter of 2022. He says the Australian market has been remarkably strong. “Honestly, we were surprised … We thought it would be more something taking time, but really, the welcoming of Chaumet has been great,” he says. He thinks it is because Chaumet represents something authentic.

“It’s about real roots, maybe also, because they have understood that Chaumet is also a lot about nature, about themes that are very [real].”