A gift to Victoria from a broken-hearted queen

In Melbourne’s Parliamentary Library is a relic of surprising intimacy, autographed by Queen Victoria as she mourned Prince Albert.

There is a lot of Victoria in Victoria — the queen in the state that bears her name, that is, and did so with great pride in the aftermath of separation from New South Wales.

There is the market, for instance, and the building, once a hospital. Melbourne features more than a hundred Victoria Streets, Roads, Groves, Parades, Avenues and Terraces.

Little, however, rises above the level of facsimile, even the statue by Englishman Marshall Wood that occupies Queen’s Hall in Victoria’s Parliament House, that cost the staggering sum of 3000 guineas.

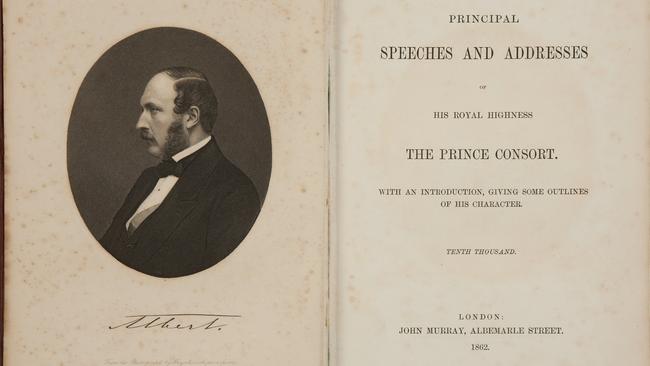

Next door in the Parliamentary Library, however, is a relic of surprising intimacy. The arrival of a handsomely bound copy of The Principal Speeches and Addresses of His Royal Highness the Prince Consort of Victoria, Queen of Great Britain, with an Introduction, Giving Some Outlines of his Character was announced on the first day of Fourth parliament on December 13, 1864.

The president of the Legislative Council, Sir James Palmer, placed it reverentially on the table in the chamber because it had come directly from, and even been autographed by, Her Majesty. The colony couldn’t claim to be among the early recipients. Albert had died in December 1861, casting the queen into loneliness and despair. “There is no one to call me Victoria now,” she said.

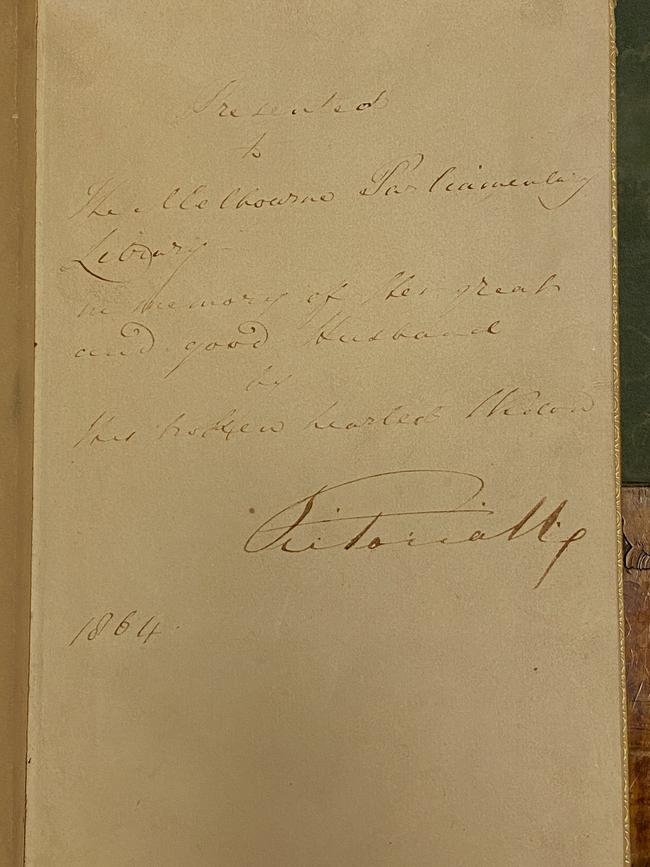

The book had been published by John Murray a year later, thus taken a further two years to make it to Melbourne. But the inscription, once dark and flourishing if now rather faded, still has a strange directness of address.

Presented to The Melbourne Parliamentary Library

In memory of her great and good husband by this broken-hearted Widow.

Queen Victoria was, of course, settling in to her role as “the archetypal Victorian mourner”, as eschatologist Pat Jalland has put it.

Withdrawing for some years from public life, emerging from seclusion still wearing black, she would become her reign’s foremost exemplar of chronic and intractable grief.

But there was something meaningful about the particular tribute of this volume. Albert had been an extremely industrious consort, speaker, writer and promoter of causes; he had, his wife confided, been “very often very trying – in his hastiness & over-love of business”.

His loss weighed specially because it so deepened and multiplied his widow’s responsibilities.

As Julia Baird says in her fine biography: “Victoria was now saddled with the chores of two people, one of whom had been a prodigious workaholic.” In this sense, by tributing his diligence, The Principal Speeches is as meaningful as any monument to him — and there were, of course, to be many of these.

The Victorian parliament’s effusive expressions of thanks for the book, not to mention the general swell of colonial condolence, would also provide some comfort, acknowledged on July 24, 1865 by Edward Cardwell, secretary of state for the colonies: “I am commanded to express to you, in reply, that the Queen has been very much gratified and soothed by the expressions of loyalty and attachment to herself and veneration for the character of the Prince Consort which are contained in your address and in the addresses which Her Majesty has received from so many other distinguished and learned bodies throughout the colonies. You will have the goodness to communicate this reply to the Committee of the Parliamentary Library of Victoria.”

Lest one think this all too personal, there is also a copy of The Principal Speeches, with an identical inscription, in the Baillieu Library at Melbourne University.

One imagines Queen Victoria almost in the mode of a modern celebrity memoirist at the signing table after a personal appearance, conscientiously individualising each copy so as best to tending her late husband’s memory and her own personality cult.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout