Smash hit, but have we heard that Mariah Carey song before?

Mariah Carey is the latest music star to be hit with a multimillion-dollar claims of plagiarism – but all is not as it seems.

Long before Robert Johnson arrived at the crossroads of Highways 49 and 61 in Clarksdale, Mississippi, legendarily offering his soul to the devil in return for his guitar chops, the essence of the blues – indeed, most music – had been ideas, lyrics and styles poached from others.

Former slaves from the south may have inched up the social order to become sharecroppers, but could only dream of music lessons for their children. Indeed, they’d been down so long it looked like up to them (and my apologies to the late Richard Farina for poaching that line).

Ambitious youngsters captivated by early blues and who were given, bought (and sometimes stole), guitars or harmonicas, learned songs replicating the lyrics, finger techniques and vocal manner of the itinerant minstrels passing through their towns.

It was pretty simple: they copied what they saw and heard. English cleric Charles Colton Caleb coined the aphorism that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. George Bernard Shaw adjusted it a century later: “Imitation is not just the sincerest form of flattery – it’s the sincerest form of learning.”

But today, with lawyers calling the tune, it is called plagiarism. And it is big business.

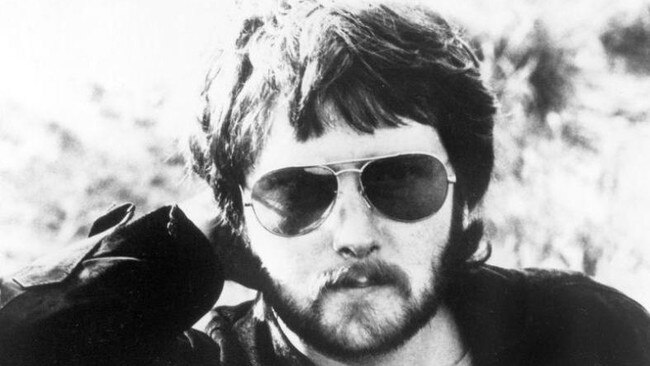

Last week, a fellow by the name of Andrew John Franichevich Jr, but calling himself Andy Stone, and appearing to have plagiarised his hairstyle from one of Phil Spector’s wacky wigs, started proceedings in a Louisiana court charging that Mariah Carey and co-songwriter Walter Afanasieff “knowingly, wilfully, and intentionally engaged in a campaign to infringe” his copyright by claiming to have written Carey’s big hit All I Want For Christmas Is You. Stone had recorded a little-known song of that name in 1989. And he wants $27.75m.

There are more than a few cases like it running at the moment, dragging towards court some of the biggest names in music: Sam Smith, Justin Bieber, Kendrick Lamar, Niki Minaj and Dua Lipa.

Lipa’s is typical of the issue facing modern musicians and singers. Her song Levitating did just that on Billboard, staying more than 70 weeks while becoming the biggest selling song in the US last year. It finally dropped out of the charts only a few weeks back.

Like most dance-hop music, it is unblushingly assembled by those who have the ear of young music fans, and no wish for new ideas or sounds.

Working with the reliable musical algorithms with which their audience is so familiar, they prefabricate pop songs. There is little art about it.

Lipa admitted to the BBC six years ago that her team “figured out what my sound was going to be – the beat, the darkness, the lyrics, the pop chorus. It’s the one I would take to new producers and say: Right, this my sound.”

Levitating may be “my sound”, but the team that wrote it includes Clarence Coffee (from the Miami-based sausage-machine music team Monsters & Strangerz), Sarah Hudson (from the Hudson family of derivative songwriters), and Stephen Kozmeniuk, whose credits coincidentally include Minaj and Lamar.

The problem is that, in recent weeks, other teams of songwriters reckon it is theirs.

One of Australia’s leading copyright lawyers, Sharon Givoni, tried to explain whether music copyright was a simple business that looked complicated, or a complicated business that seemed simple to outsiders. I mean, we all know when we have heard a song before.

“The law (of copyright) is made up of simple principles, but the application of the law is technical and complex,” she said. And it is not about quantity – how many notes or bars of music – it is about quality. This becomes subjective and often tangled.

It is why Givoni defends the decision that deemed Men at Work’s Down Under to have leant substantially on Marion Sinclair’s Girl Guides anthem Kookaburra Sits In The Old Gum Tree, despite the band having first recorded the song – identifiably so – without the famous flute riff.

“The judge in Kookaburra wasn’t particularly happy to have to come to that conclusion, but there was no escape from the proposition that there were constant references to Australia throughout Down Under … the nexus (between the late Greg Ham’s flute part and Kookaburra) was never denied,” said Givoni. “That left the court with only one question: whether it was misappropriated by Men at Work. The answer was yes.”

She described the decision as “regrettable” but correct, and added that it had led the government to consider the issues of copyright and America’s “fair use” provisions. “The role of copyright protection is to reward and incentivise creators and encourage them to create for reward.”

“Fair use” is not a legal concept here; it loosens the grip of copyright, which probably means there is little hope for the recent flourish of claims by little-known artists in the US.

Nonetheless, a stolen idea is theft no matter how “original” you wish to make it sound.

The only thing Carey’s All I Want For Christmas Is You appears to have in common with Stone’s – performed by his outfit called Vince Vance and The Valiants – is its title. The music and lyrics are different but, like the Carey song, mawkish and full of the cliches of Christmas, so Santa, presents beneath trees, sleigh bells and snow are mentioned in both songs. But that’s what you’ll get from shallow writers of manufactured pop.

The charts have long been full of hits with identical titles: Somebody To Love (Jefferson Airplane and Queen); Superstar (The Carpenters – and here by Colleen Hewitt, Taylor Swift); Photograph (Ringo Starr, Ed Sheeran); Jump (Pointer Sisters, Van Halen) and Best of My Love (The Eagles, The Emotions).

So Stone won’t get far on that. Another impediment is that an even worse song called All I Want For Christmas Is You also came out in 1989, by England’s Woodward Brothers. Never heard it? Lucky you: sleigh bells, snow, Santa – you get it.

Carey’s song has sold millions as streams and digital releases, and continues to each December. It also broke the record for phone tones (at $US2.99 a pop – more than $4) and the song is estimated to have earned up to $85m. That is why no one is suing the Woodward Brothers. A further hurdle is that Stone’s song sounds precisely like Bobby Vinton’s 1964 hit My Heart Belongs Only To You and, had I written Vinton’s song, I’d be briefing lawyers.

Artikal Sound System, a Florida, keyboard-led, reggae-influenced band reckons Lipa’s Levitating reflects its 2017 song Live Your Life. It sounds less like purposeful melodic imitation than two modern pop songs sounding much the same. But Lipa faces a more serious challenge from the authors of a 1979 song, Wiggle and Giggle All Night. Its singer, Cory Daye, is forgotten but its co-authors are not: Sandy Linzer wrote the memorable pop hit A Lover’s Concerto, a No.2 song for The Toys in 1965 (itself based on a Bach minuet), as well as Working My Way Back to You and Native New Yorker; and L. Russell Brown, who, among other hits, wrote Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree.

They believe Levitating infringes their copyright of the 1979 disco hit. Have a listen. I think they have a case.

The surge in music copyright cases is hardly a surprise given the success the estate of Marvin Gaye had against Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams over the 2013 hit Blurred Lines. That song emerged from a writing session the year before when Thicke had reportedly said he liked the “groove” of Gaye’s rightly overlooked 1977 song Got To Give It Up. The talented Pharrell promptly delivered that groove, perhaps a bit too accurately, and Thicke-by-name could see no problem with it. Nor with the objectionably puerile video that made the song infamous. He told GQ magazine: “We tried to do everything that was taboo. Bestiality, drug injections, and everything that is completely derogatory towards women. Because (we are) happily married with children.” Thicke and his then wife, actor Paula Patton, separated soon after. In 2016, Thicke and Pharrell lost a case and $7.5m to the Gaye family, a verdict upheld in 2018. The Gaye family earns half the song’s royalties and Marvin is credited as a co-writer.

One of Australia’s most acclaimed songwriters, Russell Morris, has been following the rash of cases and is not surprised, noting that only songs that have earned a lot of money ever attract attention. “The biggest disappointment here was when Colin Hay was sued for Down Under,” he said. “The melody stands if you take that flute line out of the song. It is still the song. But some people do copy. Some people get the cut-out of a song and lay something over it – use the same verse patterns and the same chord progressions.”

He was critical of the syndicate writing systems that now manufacture songs and has seen the process first-hand. “They have a formula. They have guys that go in and out of these rooms all day. I have seen it. They get four people in a room – with the artist drinking coffee or doing their nails – to nut out the song. They’ll soon be replaced by artificial intelligence.”

The most famous copyright cases have been over George Harrison’s My Sweet Lord and Led Zeppelin’s Stairway to Heaven – Harrison lost, Led Zeppelin won. But each could have gone the other way. Harrison was deemed to have subconsciously stolen the 1963 hit He’s So Fine by The Chiffons for his 1971 global chart-topper. Of course he had heard the song; The Beatles were at No.1 in the British charts with From Me To You when the Chiffons’ only hit rose to No.16. The writer, Ronnie Mack, died six months later. While My Sweet Lord was at No.1 Mack’s publisher, Bright Tunes, started court action over it. Many had recognised the similarities, including John Lennon. Harrison said years later he regretted not doing so himself.

The case dragged on and, in 1976, a court decided Harrison owed Bright Tunes $2,292,909. Devious Allen Klein, once Harrison’s manager, had secretly bought Bright Tunes for $841,217 in anticipation of such a result. In 1981, on discovering this, a court ruled that Klein should not profit from his inside knowledge and was awarded exactly what he had paid for Bright Tunes. Harrison later admitted he had been trying to copy the song Oh Happy Day.

Randy Wolfe, a teenage guitar prodigy, joined Jimi Hendrix’s band aged 15 in 1966, but his mother wouldn’t let him leave school to go with Hendrix when he relocated to London. Wolfe then founded the adventurous band Spirit and, in 1969, during Led Zeppelin’s first US tour, the bands were sometimes on the same bill. Spirit played an instrumental Wolfe had written the year before called Taurus. Jimmy Page and Robert Plant liked Spirit and would see the band on days off and even played a version of the Spirit song Fresh Garbage from the same album as Taurus.

In 1997, caught in a rip off a beach in Hawaii, Wolfe drowned after pushing his 12-year-old son to safety. He was 45 and long familiar with the likeness of Led Zeppelin’s Stairway To Heaven to his song. He thought the band should at least have thanked him. Starting in 2016, Wolfe’s estate sought to prove this in court. A setback for the Wolfe case was that the judge would not allow the songs to be played in court; only the printed music copyright would be contested. This meant the jury missed the mood, feeling, atmosphere – indeed spirit – of Taurus and its obvious likeness to Stairway, which all the world knows and is among the most valuable compositions in rock history.

Limited by this, the jury rejected the claim. Two years later this was overturned, but an appeals court reinstated the decision and, in March 2020, the US Supreme Court rejected an application to hear another appeal. Led Zeppelin had won.

Page had testified that he only became aware of the likeness when the songs were posted alongside each other on the internet. “(Taurus) was totally alien to me,” he said. Of course, Led Zeppelin had a robust reputation for lifting the music and lyrics of others and had sometimes belatedly added those authors’ names to the band’s copyrights. And despite Page claiming he was unaware of Taurus, it turned out he had a copy in his large collection. And, while record collectors collect records, musicians collect music.

-

Inspiration without the litigation

These are litigious times and music copyrights are still valuable, even if record sales are diminished. But some songwriters are still taking inspiration from the songs of others.

Perhaps the most obviously borrowed, but never litigated, piece of music is the sax riff in Gerry Rafferty’s Baker Street, one of the most famous moments in music. It defines the tune and acts as a chorus for a song without one.

For years that sax player, Raphael Ravenscroft, partly took credit for those notes. But an early draft of the song has emerged showing Rafferty working it as a guitar line, although it is possible he thought it might ultimately be reproduced on a sax. That would make sense. Rafferty, I am sure, lifted those notes from a 1968 recording by sax star Steve Markus on his jazz-rock debut album Tomorrow Never Knows. The opening sax motif on Markus’s track Half A Heart sounds very much like the opening bars of Baker Street. Markus never took action, perhaps too busy in Buddy Rich’s endlessly touring big band.

Ian Anderson, the quirky flautist with his band Jethro Tull, has never acted on the striking similarities between a song he recorded in 1969 – We Used to Know – that appeared on their breakthrough album, Stand Up, and The Eagles’ Hotel California. The two bands shared a stage in London in early 1972 when Tull’s Thick As A Brick had made them one of the world’s biggest acts. We Used to Know was in their set. In any case, Stand Up charted at No.20 in the US. Tull’s song is in 3/4 time, while Hotel California is in 4/4 and the chord sequence is not precisely the same, but listen out for Martin Barre’s guitar break and see if it reminds you of Joe Walsh. Anderson is happy to concede The Eagles may have subconsciously been influenced by his song.

Canned Heat’s first hits were knocked off from early blues artists: Going Up The Country (a reference to US draft dodgers heading to Canada) was lifted from Henry Thomas’ 1928 Bull Doze Blues; On The Road Again reworked Tommy Johnson’s Big Road Blues from the same year. He also wrote a song called Canned Heat Blues.

Al Wilson is credited on both, the original artists on neither, an issue Wilson’s creator may have raised when he overdosed in 1970.

Alan Howe

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout