Severance takes a scalpel to that pesky purgatory of work-life balance

The characters in Severance lead days of two halves – life and work – but have no idea that they are living in one and then other.

Tumbleweeds still blow across business districts everywhere. The so-called Great Resignation suggests that thousands are questioning the very nature and value of their careers. Severance (Apple TV+) is set in the same kind of vast open-plan office to which so many may never return, and it certainly won’t make anyone miss it. It’s about work as purgatory – and the lengths we’ll go to escape it.

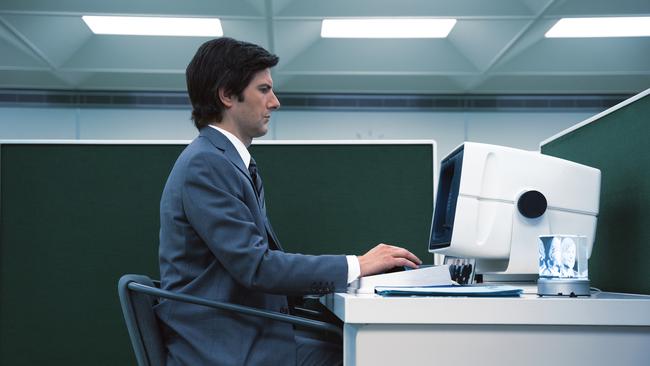

Directed and executive-produced by Ben Stiller, the series mostly takes place inside a sinister corporation with a bunker-like exterior and computers that look like vintage Macs borrowed from Apple HQ. The date is unclear, and so is the place; it resembles New England in winter. The company’s remote campus is gigantic but oddly under-peopled, with empty carparks and entire departments manned by teams of only four.

Staff are divided between those who have undergone “severance” – a surgical procedure that makes employees forget who they are at work when they’re at home, and vice versa – and those overseeing them; studying them, even, like lab technicians. And the series plays out the implications of this technology over nine episodes. Leaving work stress at the office is one thing, but what happens when human beings forgo their identities to become purely functional wage-earners?

Severance marks the first produced script from 38-year-old writer Dan Erickson, who wrote it years before the pandemic led to renewed scrutiny of the work-life balance. He was then in the middle of another career entirely, one that gifted him the material to start a new one: “In writing a script about how much I hate work, I ended up getting a job I loved.”

His screenplay landed on Stiller’s desk when the actor-filmmaker was preparing to direct Escape at Dannemora, the acclaimed limited series that premiered in 2018. And Stiller was immediately struck by the pilot script’s originality, even if he “didn’t really know exactly what the tone would be, going into it”. The result sometimes feels like a workplace comedy set in the twilight zone, with design elements that heighten the sense of claustrophobia.

The show opens with newly “severed” employee Helly (Britt Lower) racing through white-walled corridors that never seem to end, trying desperately to escape, like a rat in a maze. Her transition is supervised by Mark (Adam Scott), the leader of a small team of severed employees with whom she gradually forms an alliance.

Scott (Parks and Recreation) and Lower (High Maintenance) have both worked primarily in television comedy, and they have fun toying with office archetypes: he’s the rule-follower, she’s the rebel. These characters are essentially newborns, with no memory of their lives on the outside – and therefore no identity beyond their salaried ones. And the actors imbue them with a naïf-like quality at odds with their sinister predicament – think The Truman Show in episodic form.

Scott’s character is the only one we follow home, but the actor was careful not to show off by playing up the differences between one’s professional and domestic self, which Severance makes literal. “For an actor, often your first instinct in a situation like this is, ‘I want one of them to have a moustache, or a limp’. But it was very important that this be one guy, and it’s just different parts of one guy.”

Lower, for her part, is one of the lesser-known members of the ensemble cast, which includes Patricia Arquette, John Turturro and Christopher Walken. But her character functions as the audience’s avatar; we discover the rules of this strange new world as she does. “My job was to be in a state of discovery, investigating what is going on. One of the lines I say most often is ‘what the hell’.” That might be a clue.

The show operates as a metaphor for the way faceless corporations dehumanise work, reducing employees to dollar signs. But more broadly, says Lower, it’s about “this very human desire to want to compartmentalise parts of our lives, whether that’s work or grief, or a part of yourself that you’re at odds with. And I think the core question is, does forgetting about the painful parts of life, or the parts of yourself that you don’t like, for half a day – does that make life better or worse?”. Stiller agrees that the series questions the fundamentals: “What we’re doing in our lives, and how we’re going through this experience that we all have of being alive, and how we spend our time and what we question (and) don’t question.”

It’s heady, ambitious stuff, and more questions are posed than answered, at least in the first season. Erickson admits he originally envisaged it as a movie or limited series, and it’s easy to wonder if Severance should, in fact, have been a finite story. The show feels slightly overextended, with not enough plot to sustain nine episodes. And the pacing is off, with the big twist coming well before the climax and then simply reiterated in the finale as a cliffhanger. Mysteries need answers, at least provisionally, and it’ll be interesting to see how long this one can get away with withholding them – before the audience severs the connection.

Severance premieres on Apple TV+ on February 18.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout