One ‘mad German’ and an odyssey into the great unknown

Oskar Speck’s seven-year, 50,000km journey from Germany to Australia in a customised canvas kayak is one of the most remarkable journeys ever undertaken.

Oskar Speck’s seven-year, 50,000km journey from Germany to Australia in a customised canvas kayak is one of the most remarkable journeys ever undertaken, and the least categorisable.

Fame, curiosity, adventure, discovery: none of the traditional motivations for exploration moved him. Out of work and luck in the Great Depression, the 25-year-old seems simply to have dropped his first kayak, the 5m wooden-ribbed Sunnschein, into the Danube near Ulm in May 1932 and started paddling. “All I wanted to do was get out of Germany,” Speck would explain.

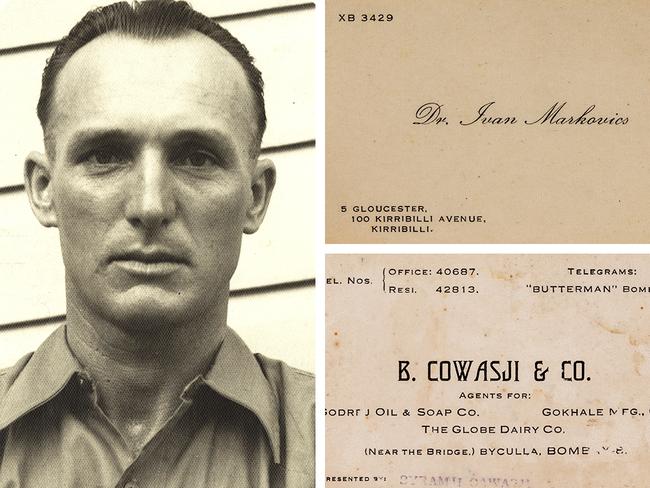

Yet he remained a loyal German, even as what this denoted changed unrecognisably during his transit, and a compulsive communicator, whose travels involved almost as many friendships as hardships. A trained electrician, he even collected the business cards of those he encountered along the way, as though he expected to return and attend their fuseboxes later: these, ragged and water-stained, are part of a collection of his ephemera in the National Maritime Museum.

There were, needless to say, numerous scrapes. Forbidden passage through the Suez Canal, Speck had to travel 320km by bus through Syria to the Euphrates, with the additional complication of needing to bribe corrupt police who impounded his kayak.

When the Sunnschein was damaged in the dusty port city of Bandar Abbas on the Strait of Hormuz, he had to wait six months for a replacement to arrive from Germany and for his constitution to recover from malaria.

He used a total of five kayaks on the journey, his sole concession to distance the addition of a gaff sail for favourable winds and a storage space in place of a second seat.

In Asia, Speck had better luck. Arriving in Baluchistan at British India’s far west, he was warmly greeted by the top local official: “Let me congratulate you, Mr Speck. A splendid performance.” He became something of a raj celebrity, affected a pith helmet and khaki shorts, and claimed a kinship and rivalry with its mad dogs and Englishmen: “But I think a mad German is madder than any of them.”

Opportunistically, Speck also claimed to be an embodiment of Hitler’s campaign to restore his nation’s former greatness, about which he remained stubbornly naive: “For whom am I risking my life, what am I promoting with my spectacular sporting achievement? It’s the new Germany.” He had no compunction about flying a Swastika pennant from his kayak.

By now, 1936, the Antipodes glimmered distantly. Having worked his way round India and Ceylon, he decided in Colombo to press on to Australia. From Burma he threaded his way through the Andaman Sea to Singapore via Penang.

Here he entered perhaps the toughest part of his journey – Sumatra, Batavia (Djakarta), Surabaya, Bali, Dili, Leti and Moa. Battling punishing weather, worsening health and hostile locals, he subsisted on a paddling diet of water mixed with sweetened condensed milk, cheese and milk chocolate.

On Lakor in the Timor Sea in October 1937, Speck almost came undone completely. While asleep on a beach awaiting a morning tide, he was accosted by restless natives who took offence at his brandishing a pistol.

They beat him savagely, bound him tightly and plundered his supplies, being particularly enchanted by the pith helmet. When their backs were turned, however, Speck managed to chew through his bonds and make his escape, doubling back to Surabaya for medical attention. He convalesced there for five months.

Because the Dutch colonial administration would not authorise his travelling, Speck then had to circum-navigate New Guinea, starting in Manokwari, for where he sent a bevy of letters to friends and family pleading for money to rebuild his resources.

He was staggeringly successful. Donations enabled him to retrieve a 16mm camera from a pawnbroker and take remarkable footage of Papuan tribal dances and customs.

Hereabouts, in September 1939, the world Speck had left finally caught him up. After an overnight 430km journey from Port Moresby to Daru, he learned that the country he had left was at war with the country of his destination. When he dragged his Swastika-bearing kayak ashore on Saibai Island a couple of days later, Speck was greeted by a band of bemused Melanesians and three bush policemen. “Congratulations on an incredible achievement, Herr Speck,” said one. “I regret to inform you that you are under arrest.”

Needless to say, this left Speck feeling a little under-appreciated. He had expected to be “garlanded and carried in procession”. Instead he would not be released from internment until January 1946, and his story has inspired no legend, no book or adaptation.

His journey was simply too eccentric and Speck himself too remote.

Travel did not broaden his mind: he was neither observant nor introspective; he was oblivious to disintegrating colonialism and incipient nationalism he encountered along the way; he simply ploughed on, as he did in life, never seeing his parents again, never marrying or having children, surrounded until his death in 1995 by mementos of the scarcely believable.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout