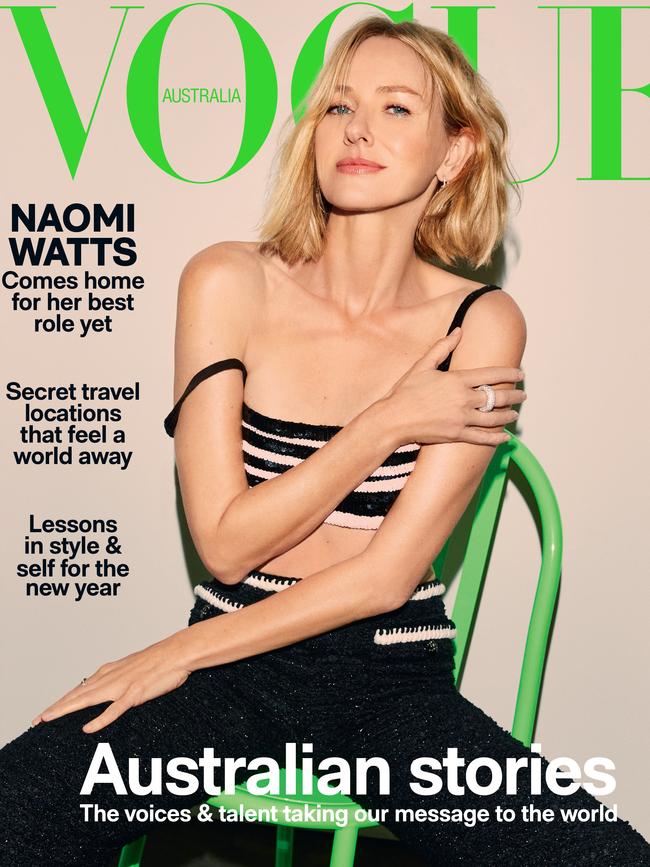

Naomi Watts on lockdown in New York, family and her magpie co-star

Naomi Watts returns to screens in Penguin Bloom, the story of how one magpie helped heal and restore hope to a devastated family.

Naomi Watts is talking about co-starring in her new movie with a magpie when she stops mid-sentence. “I just have to tell you something,” she says. Her tone is conspiratorial. I think she might be about to divulge a great secret but that’s not where she takes the conversation.

“I’m looking at a praying mantis that’s trying to get into my room! Can I show you?” To achieve the best-quality audio for our Zoom call, the video is off; for a moment now we switch it back on. Watts, wearing a cream sweater with stars, big spectacles and no apparent make-up, manoeuvres her laptop until its camera reveals the green insect on the other side of a windowpane beside her. “Can you see it there?” She’s excited. “At first I was like, it’s a stick moving in the wind but there’s no wind; they’re extraordinary creatures, aren’t they!” The actor paddles her arms up and down in front of her, mimicking the insect’s movements.

The bio-diversion confirms the impression I have been forming: Naomi Watts, 52 years old, English-born, Australian-raised, two-time Oscar best actress nominee (for 21 Grams and The Impossible), red-carpet regular, New York resident, habitué of the Hamptons, amicable co-parent of two young boys with her former partner actor Liev Schreiber, paparazzi target (most recently caught looking loved-up with The Morning Show’s Billy Crudup), is warm, candid and real … and has an affinity for some, if not all wildlife.

The actor’s new film, Penguin Bloom, based on the true story of the Bloom family of Sydney’s Northern Beaches – Cameron and Sam and their sons, Reuben, Noah and Oliver – is the confluence of two remarkable storylines: Sam’s battle for survival after suffering devastating injuries when a railing she was leaning on broke and she fell six metres during a holiday in Thailand in 2013, and the healing power of a plucky baby magpie who arrived in the family’s life when Sam was in a world of pain and depression, unable to comprehend how she could spend the rest of her life in a wheelchair.

Watts was required to have some intimacy with the multiple magpies that played Penguin. On the first day on set, a scene required her to let one of the birds perch on her head. “It just sat there and let a movement come trickling down onto my face … it travelled right down the centre of my face,” the actor says. “I opened my mouth with sort of a half scream and half laughter and it went straight into my throat. Luckily I’m not squeamish about stuff like that. I’m a bit of a farm girl at heart.”

Behind the monitor, director Glendyn Ivin watched with some anxiety. “I did have this moment of thinking: ‘This could go two ways,’” Ivin says. “Like if Naomi just cracked it and went: ‘This is bullshit, like what the hell is going on …’” Instead she laughed uproariously. Perhaps he should have known she would be cool about it: months before filming, he had travelled to New York to spend time with her going over the script. He had a wheelchair dropped off at her apartment so she could start to feel how it was to be in it and she spent the whole time he was with her in the chair. “She wants to do the best job she can between ‘action’ and ‘cut’ and to do that she requires very little.”

Watts, who was a co-producer on the film, the first she has shot in Australia since Adore in 2013, was less comfortable with the catering for the magpies – mealworms. “Naomi said at one point: ‘I don’t really mind birds but I have a thing about worms,’” Ivin recalls. The worms, an essential treat in the bird trainer’s toolkit, were everywhere, including in the bed on-set where, as Sam Bloom, Watts spent chunks of time. “I would say there were hundreds of worms in that bed, wriggling around her … And at the end of a take, I’d say: ‘How are you going with everything?’ And she just goes: ‘All I can feel are mealworms crawling around my stomach right now.’ It is pretty weird to know that you’ve got this wonderful, beautiful actress laying in a bed of worms … and trying to be as calm and still as possible.”

The magpie that saved a family and became the subject of Watts’s new film fell from its nest soon after Sam Bloom returned home after six months in hospital. Noah Bloom found the injured chick on the ground near his grandmother’s house and convinced his parents the family should raise her until she was strong enough to fly. They called her Penguin for her plumage and Cameron, a photographer, started taking pics: Penguin snuggled in a scarf or in bed with Sam or one of the boys, Penguin clutching a toy monkey, Penguin gently pecking Sam’s face. “And then the boys said: ‘Why don’t you start an Instagram account for Penguin?’,” recalls Cameron, sitting at a long table in the family’s bungalow high on a hill in Newport on Sydney’s Northern Beaches, which was used as the location for the film.

Sam almost always refused to be photographed; when she was, her husband shot her from behind, her wheelchair out of frame. “I didn’t want to be photographed in a wheelchair,” says Sam, who was a mad-keen surfer before the accident. “I was embarrassed, it wasn’t me.” I notice Sam’s sweet and gentle manner, her cowrie shell and string necklaces, and lean, muscular upper body long before I notice her wheelchair.

The Instagram account (@penguinthemagpie) was a sensation; the book that followed a bestseller. Penguin Bloom: The Odd Little Bird Who Saved a Family told the story of how Penguin’s playfulness and resilience lifted Sam’s spirits so she was able to face her altered life. With initial trepidation and then ruthless determination, she started kayaking. Two years after the accident, she became a member of the Australian para-canoe team for the 2015 World Championships in Italy.

Australian film producer Emma Cooper mailed Watts a copy of the book. “Do you think this could make a movie?” Cooper asked her old friend. Watts opened the package on a Sunday morning. “It was a lazy morning in bed with the children,” she says. “And I just pulled it out and I saw a lot of these really compelling images that were so beautiful, and something to share with the children.” When she’d finished flicking through the book with her sons, Sasha, 13, and Kai, 12, they went back and read it from cover to cover. “It was just such a beautiful story about how a broken family comes together and repairs itself, and a story of hope and resilience.”

From the moment Watts and Sam met, they developed a powerful connection. To help Watts prepare for the role, Sam gave the actress her raw and painful diaries to read. During filming, they would sit side-by-side on the lawn outside the house and talk quietly. Frequently, Watts asked Sam to stay on set; sometimes she would ask questions about how to do a particular movement, for example, how she should get dressed or lift herself from the bed to the wheelchair. Or she would take Sam’s hand and look in her eyes to get herself into “the space” required to play the role, to become a container for Sam’s pain and anguish. The Blooms were moved by her compassion and warmth. “She was so lovely, she’d always say sorry when she jumped up from the wheelchair because she felt guilty. She’s got a big heart, Naomi,” says Sam.

Watts is at her LA home when we talk. “If you hear an invasion, forgive me, it’s how the world goes right now with kids.” Winter is settling over New York and she has travelled west with her boys and her pandemic rescue puppy, Izzy, seeking warmth after a wonky year that started with a blissfully innocent Australian holiday. At the tail end of 2019, she posted a photo to her irrepressible Instagram account of her and her oldest friend, fellow actor Rebecca Rigg, on a beach. “2020 we are coming for you!” she wrote in the caption. Now she refers to the past year as a “shitshow”; in an October post she gives it the finger – “From me to you 2020,” it says.

Watts spent the early days of COVID-19 isolating in her New York apartment with her boys as one film project after another stalled and ideas fell over. For a while she had been interested in the philosophy of the progressive Living School in the Northern Rivers of New South Wales, run by friends of hers, and she decided it might be a great opportunity to enrol the boys in a term at the school. “I was literally so jazzed up about this possibility. I was pitching it to Liev … for our kids; it’s all about growing things and making things and just common sense, life skills.” Then she learned that restrictions on international travel meant she wouldn’t be able to get the boys back to Australia. So they hunkered down at home; she supervised their online schooling and tried to help them deal with the disappointment of not seeing their friends and managed her own anxieties with cake, bowls of pasta and raids on her sons’ Oreos supply.

When the New York lockdown eased in July they took off for summer in the Hamptons. Watts recently sold her house in the seaside village of Amagansett so she rented a place, although Schreiber and her brother, photographer Ben Watts, both have homes there. As the bizarre year wore on, he shot his sister twice on the beach for stories in American titles – in summer in swimwear and, in autumn, luminous and windswept in cream sweaters and blue denim. “My brother definitely knows how to catch the spirit of his little sister,” says Watts, who had a hair and make-up artist on FaceTime while she did DIY glam for the shoots.

In Penguin Bloom, Watts’s kayaking technique seems Olympian but she disagrees when I suggest she must be a water baby: she didn’t move to Australia until she was 14 and ever since she was caught in a rip in Bali when she was a teenager, she has been wary of the ocean. Nor is it in her interest professionally to spend too much time in the sun. Her skin is pristine and she cares for it diligently. She is also the co-founder and owner of the clean-beauty business Onda Beauty, which has stores in Tribeca and Sag Harbor in the US and Notting Hill in London, and opened its first Australian boutique in Paddington in 2019. “I love the beach but … not for baking oil into my skin and tanning. I like it for the smells. I like it for the feel of sand and crunching between your toes. I like the wind and the wispy hair.”

Petite puppy Izzy, a Yorkshire terrier-chihuahua mix, is barking in the background as Watts tells me she thinks she’s misunderstood. I have commented on her Instagram account, an engaging catalogue of a lovely life which is surprisingly revealing and real given her public profile – snaps of Sasha and Kai, mad TikTok dances starring the whole family including Schreiber, Watts without make-up, pulling ugly faces in front of a John Olsen artwork in her lounge room, hugging her friends including Nicole Kidman, wielding a mop, laughing with her nana and showing slightly crooked teeth, and losing her shit over broken appliances during quarantine (perhaps inspired by American fitness phenomenon Taryn Toomey’s live-streamed The Class, which Watts regularly takes and which encourages participants to scream and shake out their tension). “Are you this adorably goofball in real life????” one commenter asked alongside a shot of Watts being nutty in leisurewear.

“Yeah, look, I can only do me, right,” Watts tells me. “I think I opened up a whole lot more during Covid … I needed to laugh.

I liked that other people might get a laugh out of some stupid things, me sending myself up.” She says people might think of her as an actor who only does dark serious films, but she loves to laugh. “I’ll do anything for the joke!”

Her honesty carries through to the types of roles that interest her. She looks for women who are going through something like Sam Bloom, who change in some way through the course of the story. They don’t have to be heroic; it’s the transformation that matters.

At this point in our conversation she mentions her late father, Peter, a road manager and sound engineer who worked with Pink Floyd. He and her mother (Myfanwy, or “Miv”) divorced when Watts was four; four years later her father was found dead, apparently of a heroin overdose.

“I would say there’s things that I grapple with in my own psychology, and that definitely presents itself in my creativity.” Two themes emerge time and again – grief and identity. “Having grown up losing my dad at a very early age, I think that’s a story I know well; it’s still sorting itself out at the ripe age of 52. Through that, you lose a part of yourself … you feel like you’re not fully formed in a way.” Watts is still surprised sometimes by the force of emotion that hits her when her father comes up in conversation. “It sort of happened to me the other day and I felt really embarrassed to be having an emotional reaction.”

In the shitstorm of 2020, Watts was deliriously excited to be able to complete one project: in September, after quarantining, she filmed Australian director Phillip Noyce’s thriller Lakewood in Ontario, Canada, about a mother desperately racing to save her child. “When I got that first call sheet, I nearly burst into tears. I was like: ‘Oh my god, yes, we get to be creative again.’”

Such is the film industry’s state of flux that Watts won’t reveal what projects lie ahead, other than to say she has a couple of balls in the air. She is interested in doing more work as a producer and reveals that two ideas she stumbled across are getting to the point where “all things going well, we might have a final product at some point”.

She also politely declines to talk about her relationship with Billy Crudup, who she met while filming the 2017 Netflix series, Gypsy, a Manhattan-set thriller in which she stars as a therapist and Crudup is her on-screen husband. “We’ll keep it private for now and see where we go,” says Watts, who separated from Schreiber in 2016 after 11 years together.

After the 2001 release of Mulholland Drive, the film that set Watts on the road to super-stardom, director David Lynch told the Los Angeles Times that the actress has “a beautiful soul”. On one of the last days on the set of Penguin Bloom, Watts gave every member of the cast and crew a gift she had made specially – a cloth bag featuring the image of a magpie. Now, as the allocated time for my interview runs out, another call for her comes in. Her grandmother is FaceTiming her from Australia. “Hi Nana, hold on,” Watts says in a voice loaded with affection. She turns back to speak to me: “Shall we put the camera on just to say goodbye?”

Penguin Bloom is in cinemas January 21.

Vogue’s January issue is on stands January 11.