‘My name is Cleo’: Miracle ending to the rarest of crimes

Detectives kept an open mind on the search for Cleo – a hard case with a miracle ending.

It had the most unexpected joyful ending. Not only was little Cleo Smith alive, but she was the apparent survivor of the rarest of crimes – a stranger abduction.

The miraculous discovery by police of four-year-old Cleo locked inside a house 18 days after she disappeared is once again a lesson in not jumping to conclusions in criminal investigations, particularly when a child goes missing.

How many people can honestly say they did not suspect someone close to her was involved in her mystery vanishing, when – according to police on Wednesday – the culprit was a 36-year-old man with no connection to her family in what appears to be an opportunistic crime.

Cleo’s rescue is rightfully making global headlines as an incredible feel-good story. While only time will reveal the extent of any damage inflicted on an innocent young girl snatched from the safety of her family’s tent, a picture of Cleo smiling and waving in hospital only further boosted the mood of a nation that has been anxiously following every twist and turn in the saga.

What we know so far of the disappearance and recovery already reads like the script from a big-screen blockbuster, and will no doubt be turned into one.

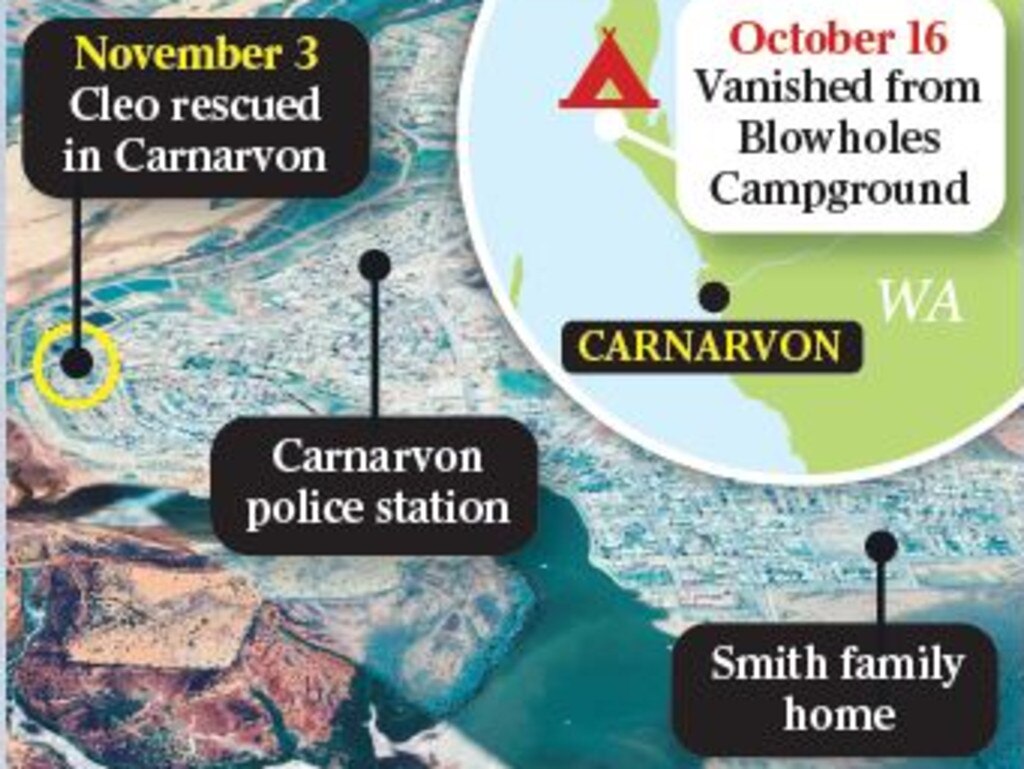

A young girl with honey-blonde hair and hazel eyes is put to bed while camping with her family on Western Australia’s rugged Coral Coast.

The next morning she is missing along with her sleeping bag, the zipper of the tent pulled up high, beyond the girl’s reach.

What could possibly explain such a scenario?

The WA police made their suspicions known early, offering an almost instant $1m reward. Usually such measures are reserved for cold cases, not those in which the dust from the searchers’ feet is yet to settle. Police have said it wasn’t what led to the breakthrough.

We now know the ending – if not the full story.

In the early hours of Wednesday morning, police stormed into a home in Carnarvon, about 900km north of Perth, and found Cleo locked in a room inside.

They asked her name and she gave the confirmation they were praying for, in four brilliant little words: “My name is Cleo.”

The title for the future movie could well be those four words that brought a tear of joy and relief to many an observer’s eye.

If only all such missing children cases ended this way. William Tyrrell, Daniel Morcombe and Azaria Chamberlain are three of Australia’s most famous cases of children going missing.

All deeply resonated with Australians, and all involved very different circumstances and resolutions – or, in William’s case, no resolution at all.

Three-year-old William vanished from his foster grandmother’s house in Kendall, NSW, seven years ago. He has still not been found, and no one has been charged. Police investigations are continuing.

Daniel, 13, went missing from a bus stop on the Sunshine Coast in 2003. An undercover police operation known as the Mr Big sting duped his killer – serial child-sex offender Brett Peter Cowan – into leading officers to his remains on a farm almost eight years later.

Nine-week-old Azaria Chamberlain’s disappearance from her tent during a family camping trip at Uluru led to her mother, Lindy, being wrongly jailed for her murder, before she was exonerated.

After the fourth inquest into Azaria’s death, a coroner found in 2012 she was in fact attacked and killed by a dingo, as her mother had stated from the outset.

Former NSW homicide detective Stuart Wilkins worked on the William Tyrrell investigation in its infancy as the acting regional commander and, prior to that, the Ivan Milat backpacker murders. He retired as a detective superintendent and is full of praise for the WA investigators.

“It appears they have done a fantastic job in keeping an open mind and looking at everything,” Wilkins says.

“They clearly had some compelling information that made them go through that door.”

Wilkins says close family members are “always an avenue of investigation”, and for good reason.

“You will see, statistically, that people are murdered in high percentage by people they know.

“The random attack is rare,” he says. “Certainly, the family is one of the first investigative processes you will go through.

“In every one of these child abductions or murders, they look very closely at the family first, or the family circle as well.

“Percentage-wise, it’s quite high that it comes from one of the family members or one of those in the close family circle.”

He says those checks are vital, and a good detective will always explain to the family that it’s a requirement. But that’s just one avenue of investigation.

“Clearly, the West Australian investigators have done a wonderful job because they haven’t just looked at the immediate vicinity. They have looked at all avenues,” Wilkins adds.

“People talk about tunnel vision and you’d hope that it never happens, but it does at times and I have seen it happen. People do get very obsessed with one particular line of inquiry and they miss others.

“But the more you do in homicide investigations and the bigger they get – and refer back to the backpacker murders where you had hundreds of suspects – you can’t just keep one vision into one group. You need to keep an open mind until such time as you know who it is.”

The abduction of a child by a stranger is every parent’s worst nightmare. It is an extremely rare event, but one that does happen.

“They are the rarest type and probably the most heinous, the worst of the worst that you can investigate,” Wilkins says.

“There is some media around (saying) that Australia is the capital of child abductions. Well, it’s not. You can count them on one hand, to be honest.

“You’ve got Samantha Knight, you’ve got the Beaumont children and you’ve got William Tyrrell and Daniel Morcombe. There are not masses of them. They don’t happen very often and they do get significant media and community coverage.”

Samantha Knight, nine, disappeared from near her Bondi home in NSW in 1986. She was killed by pedophile Michael Guider, who has never revealed the location of her body.

Beaumont children Jane, nine, Arnna, seven, and Grant, four, disappeared from Glenelg Beach in Adelaide on January 26, 1966, and have never been found.

Wilkins says the public often knows little about what is really happening inside a police investigation, especially in the early stages. “Everyone’s got an opinion. No one has got any concept of what the cops are doing in the background or what information they have. That includes the media because the media don’t always know.

“The cops aren’t telling everybody anything unless they have to for a strategic reason or purpose.”

He says that the chance of finding Cleo alive after a stranger abduction “was probably quite low”.

“While we all hoped and prayed she’d be found alive, there weren’t many people, I would have thought, after three weeks thinking that was going to happen.”

Former Queensland Police homicide detective Scott Furlong believes many people “would have had a thought that it was somebody known to the family or a close family member or a relative or associate” involved in Cleo’s disappearance.

He says assumptions can have a negative effect on investigations when police are wanting to hear from anyone who may have any information, no matter how small.

“Never put the blinkers on, don’t look too narrow, and if you have any sort of suspicion in your mind tell the police,” Furlong says.

“If you think ‘I heard this’ or ‘I saw this but I don’t think that was associated with the family’, tell the police anyway because they will investigate it. It just might be that little bit of information that turns things on its head.”

Furlong cites the disappearance of three-year-old Anthony “AJ” Elfalak from his family’s property in NSW in September as a more recent example of common perceptions being proven wrong.

A search helicopter spotted little AJ lost in bushland and drinking muddy water from a puddle 72 hours after he went missing – and after family members raised fears he had been abducted.

“Everyone was thinking the worst in relation to that – and here he is, they find him in a creek,” Furlong says. “The important thing is you don’t put these investigations into boxes. You don’t just fit it in and say this is this type of investigation. You have got to keep that broad mind.”

The offer of a major reward early in the investigation was a significant move that may be looked at more closely in future in other jurisdictions, where there are different guidelines and procedures for offering cash incentives for people to come forward.

“You’ve got a young child involved and if there’s any opportunity that you have to either successfully recover the child or repatriate a child with their family, you’re going to do that,” Furlong says.

“They had their reasons for doing it and I think they’re sound, whether or not it generated any sort of leads.

“It could just come down to the assertiveness of the powers that be that are there at the time. They must have thought, ‘We have an opportunity to recover the child – this might help’.

“That’s keeping that broad-minded view – that we don’t know what’s happened to this child, could a million dollars appeal to somebody out there to give us some information as to where the child might be.

“It’s just the blessings of God we got her back.”

Furlong says Cleo’s case is also a good reminder to hold fire on public condemnation until the facts are known.

“There’s something to say regarding some of the online abuse from trolls that the family got as a result of it,” he says.

“People would have thought they were involved. It’s a lesson in just pulling your head in a bit – you don’t know what’s happened, you don’t know the circumstances or the dynamics around everything that happens in the world. There’s no need to vent your frustration and feelings online at a family that would quite obviously be grieving.

“I wouldn’t know what it would be like to have your child go missing and not know where they are and not be able to protect them. It must just be the ultimate form of torture.”

The discovery will give hope to families of other children who remain missing that there could still be a positive outcome. Two people who know the agony of the other side of the coin, when a child is not found safely, expressed their joy at Cleo’s discovery on Wednesday.

“Wonderful news to hear Cleo Smith has been found safe and well and reunited with her family,” tweeted Daniel Morcombe’s parents Bruce and Denise.

“Excellent detective work by Western Australian Police and a vigilant community.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout