My Covid-19 ordeal in Jakarta

Seriously ill with Covid, Jakarta-based journalist Amanda Hodge witnesses first-hand a country buckling under the strain of the Delta surge.

I wake to a room spinning violently. My eyes are open but my vision has deserted me and I suddenly feel like I’m clinging to consciousness. In a panic I try to reach the door of the spare room in our Jakarta home, where I moved as my health deteriorated from Covid-19. Instead, I fall to the floor and lie there, pinned by an internal, centrifugal force.

It has been 10 days since I tested positive for coronavirus, along with my partner Graham and our six-year-old daughter. Thankfully, she suffered only a day of mild fever and headache, yet I am clearly getting sicker – even as I assure friends, family and colleagues that I am poised to turn a corner. I have my sense of smell and taste, but I cannot eat. My body aches with a deep bone soreness that triggers flashbacks to a past dengue infection. I am managing the constant fever with paracetamol, though nothing seems to ease the violent cough or the feeling that walls are closing in on my lungs.

As two fit, middle-aged adults with no previous health worries, we rely on the fingertip Oximeter to monitor oxygen levels, confident we will push though the illness and reluctant to trouble an overburdened Indonesian health system struggling with a new surge of infections. If we can breathe we’re OK. Yet here I lie, unable to move and temporarily blind. I am not OK. No one in the house hears my calls for help. I ring the international medical clinic on the south side of Indonesia’s sprawling capital city. The night duty doctor tells me I need to go to hospital, but they have no spare ambulances or beds and are running out of oxygen. With no help coming, no idea what is happening to me, and the city in a state of quiet emergency, I do as she urges and scream.

At dawn we leave our bleary-eyed daughter with her babysitter, who only days earlier had secured her first jab, promising to be back soon. We drive to a hospital we are told might have an emergency bed. In the end we need two.

We moved to Jakarta from New Delhi in January 2016 after seven years of pivoting across South Asia’s trouble spots to cover war in Afghanistan and Sri Lanka, floods and terrorism in Pakistan, earthquakes in Nepal and refugee crises in Bangladesh. Indonesia was the family- friendly bureau we chose to dial down the risks of the job in an age when a pandemic was a sci-fi script, not the epochal event of our time. Its underfunded health system was a drawback, but the world-class specialists and hospitals of Singapore were just a short flight away – until the pandemic hit and borders closed.

Like many, we temporarily returned to the safety of Australia in late March 2020 on the embassy’s advice, leaving everything behind. I went back alone in August to report on how the biggest story of our era was unfolding in Australia’s neighbourhood. Indonesia’s death rate, then as now, was the highest in the region and hundreds of medical workers had died for lack of proper protective equipment. Case numbers were deceptively low – on average 1600 new cases were being detected daily in August last year within a population of 270 million – thanks to pitifully low national testing rates of about 10,000 people a day that allowed the government to argue Indonesia was successfully handling the virus.

The country was a confusion of mixed messages; a few government ministers were insisting eucalyptus necklaces could protect against the virus, though in Jakarta social restrictions were enforced including compulsory mask-wearing in indoor public places. Children were not allowed to go to school or playgrounds, but were free to go to malls, cinemas or travel on planes with their parents.

I kept my life small, working largely at home and seeing a handful of people. It wasn’t much fun but the risks seemed manageable. In January, with Indonesian infection rates still steady and our little family unwilling to endure more separation, we returned to Jakarta together. It seemed a reasonable, calculated risk before the voracious Delta mutation changed all calculations. In the airy upmarket malls and supermarkets, public health orders for compulsory masks and hand sanitiser were strictly observed, but there was less compliance in the poor and dense kampungs and traditional markets where the virus was silently multiplying.

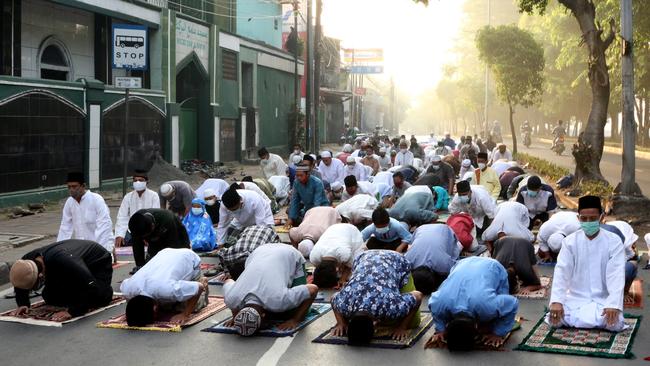

As the US began to open up in March and April after a nightmare year of Covid lockdowns, we watched warily as Indonesia relaxed further. Four months into its own vaccination roll-out, the country was finding a “new normal” and a false confidence aided by official daily Covid figures kept artificially low. Jakarta’s infamous traffic gridlocks returned. Our daughter was still online learning, along with millions of Indonesian school kids. We worked mostly from home, had groceries delivered outside the gates, and saw only a handful of careful friends. We barely left the house, wore masks when we did and had regular PCR tests. Then, in late May, millions of Indonesians travelled home to their families for Eid.

The woman across the narrow aisle of the makeshift ER is looking my way but straight through me. The numbers on her ventilator are the only things blinking – 83, 85, 79… Her black hair, greying at the temple, is plastered to her head despite the freezing air conditioning – presumably for the benefit of medical workers wrapped head to toe in protective plastic and latex. “That can’t be good for Covid pneumonia patients,” I think vaguely, but there are no extra blankets. Even in mid-June, before Jakarta’s health system buckled under the pressure of a new viral surge, every bed is full. I can’t move without everything spinning; a symptom initially ascribed as “vertigo” but it seems could have been a Covid-induced mini stroke, yet another neurological manifestation of a mutating coronavirus doing a third sweep of the globe and targeting many who thought they’d dodged a bullet.

Hours later, my bed is wheeled into a makeshift radiology room and a large X-ray plate is slid under my back. The picture is grim. Coronavirus has infiltrated both lungs and I am no longer one of the healthy, younger humans for whom the virus is a seven-day inconvenience. My tall, fit partner’s lungs are even cloudier. The virus has developed into the “ground glass” Covid pneumonia that has proven deadly for 4.5 million people worldwide. The ER doctor tells us we are to be admitted. We, who punish the treadmill, whose job is to document disasters – not get caught up in them – are now in hospital, two more statistics, while our only child is at home, Covid-positive with a vulnerable nanny.

The doctor doesn’t ask if we have been vaccinated. Less than 6 per cent of Indonesians had been by early June, and foreigners were at the back of the queue. Even those who had been fully vaccinated, largely with the Chinese-produced Sinovac that has underpinned the country’s vaccination campaign, were falling ill. Some were even dying. Still, those who had not been inoculated were far worse off. And we were unvaccinated. Like millions of expatriates, we were ineligible for a jab in Indonesia when the rollout began in January. The Australian government was still insisting there was no rush to vaccinate, and its Jakarta embassy was firm it would only be inoculating its own staff. It took until June, when more vaccines arrived and a private scheme kicked off allowing businesses to vaccinate their workers, for the general Indonesian population to have access, though a vaccine drought in July slowed the rollout just as desperation reached a crescendo.

Foreigners fared better in Bali, where the government prioritised vaccinations in the hope of reopening to tourists in July. But in Jakarta vaccines were hard to get. We signed on, with some reservations, to the journalist list for the Sinovac jab in January, only to be struck off as foreign nationals. Months later we registered for the private scheme but were told it could be November before our numbers came up. When the Delta variant began sweeping through New Delhi in April, we knew our luck could not hold and booked flights to Australia for a vaccine. The soonest we could get was June 13. We made a backup plan, securing US tourist visas so we could quickly pivot to New York (at half the cost of our Australian tickets) for a tourist jab if we got bumped off our Australian flights, as many others had. We thought we had it covered. Then, six days before departure, we fell ill.

It takes a few days after a person is infected with Covid-19 for their body’s immune system to start attacking cells containing the virus. A vaccinated person’s system reacts much faster and with greater vigour than that of an unvaccinated one, whose body does not recognise the virus and can take up to two weeks to learn how to fight it – plenty of time for the virus to turn an initial infection into a serious disease. In my case, I suffered a fortnight of symptoms – sore throat, fatigue, a persistent dry cough – before finally testing positive. I had already had one negative result and a series of inconclusive blood tests by the time Graham fell ill with fever and we both went for yet another test that confirmed it was Covid.

By early August, more than 30 per cent of the world’s population had received at least one jab of a Covid-19 vaccine, the vast majority of them in the wealthy West, according to the Oxford University- based Our World in Data team. In low-income countries that proportion falls to just 1.1 per cent, leaving the poorest most exposed. The world watched as Delta swept mercilessly through the largely unvaccinated populations of India, and then Indonesia, where less than 15 per cent of the population had then received a single jab. In both countries it attacked millions of younger adults who had escaped infection in earlier surges, were not a priority for vaccinations and were less risk averse.

Covid-19 infections and deaths in Indonesia almost doubled through June, July and early August, when more than 1.6 million new infections were added and 45,000 people officially died. The country’s true toll may never be known because so many Indonesians cannot afford a “gold standard” PCR test and only deaths from confirmed Covid infections are counted in the statistics. But an eye-opening, government-commissioned serology survey of Jakarta recently found 44.5 per cent of Jakarta residents had antibodies to the SARS Cov-2 virus by March this year, indicating they had had the virus, though only 8.1 per cent of them had been tested and confirmed Covid-positive. The survey was conducted months before the city of 10.6 million people became the global centre of the pandemic in an awful replay of India’s trauma.

Again, ambulance sirens wailed through the night, people made desperate online appeals for oxygen cylinders and overwhelmed cemetery workers buried two to a grave. Indonesia’s Covid-19 death rate per million rose to the highest in the world. It is still almost double the global average. Worse yet, it has one of the highest Covid-19 child death rates due to pre-existing high levels of respiratory disease among many of its very young. Some 1272 Indonesian children have officially died of Covid, a record 228 of them in August 2021. Three million Indonesians have slipped back into poverty as a result of the local and regional restrictions that have slashed the meagre daily wages of millions of irregular workers and decimated its tourism industry, even as public health experts call for stricter measures. Tens of thousands of children have lost one or both parents to Covid.

Taiwan and Vietnam, two countries consistently praised for their handling of the pandemic, have also struggled to contain recent, fresh outbreaks amid a vaccine shortage. By far the most vulnerable, however, are nations such as Indonesia, Myanmar, The Philippines and Cambodia that not only have vaccine shortages but poor health systems as well. Australian citizens in those countries have pleaded repeatedly for the Morrison government to follow the French example and arrange vaccinations for vulnerable expatriates who are unable to access one where they are and cannot return to Australia because of slashed weekly arrivals caps and soaring flight costs.

Canberra recently accepted Thailand’s offer to vaccinate non-nationals and says it has had discussions on the topic with Indonesia. But it is promising nothing. “The level of desperation among expats trying to get a vaccination here is crazy and in Australia you have (AstraZeneca) vaccinations sitting in a fridge,” says Bali-based Australian Charlie Knoles, who runs a Telegram social media group for almost 700 expats and Indonesians providing daily updates on where they might secure a vaccination. “The French nationals in Indonesia are all getting an approved French vaccine here. The Australian government could do that with no problems. Australia has pledged 2.5 million vaccine doses to Indonesia. Could they not have added an extra 5000 for Australian expats here? It’s like the government has already written us off for dead.”

The private Jakarta hospital is one of the betterones in the city though it is vast and unfinished, its elevators unsealed and thick with builder’s dust. The uncomfortable hospital gurneys can only be adjusted manually from the foot of the bed. Blankets are scarce and food from home is advisable. Secondary infections are an obvious risk. Within a day of admission we are asked to pay a $10,000 deposit. A day later the hospital wants another $20,000. It is a hospital for those who can afford to pay, though even then there is a queue of sick people with money waiting for a bed. We are lucky to have a bed when millions can’t get treatment.

Oxygen flows through my nasal cannula while fellow Jakartans in coming weeks will form desperate queues for oxygen cylinders and basic medicines. I receive vein-busting volumes of drugs: Remdesevir, the ebola drug recently approved for hospitalised Covid patients; the steroid dexamethasone, to limit the risk of a so-called cytokine storm from an overreaction of the body’s immune system; and immunoglobulin, an antibody-rich human blood plasma, to manage the effects of the steroids. There is a daily shot of the blood thinner Heparin, Tramadol for the headaches and thick vials of liquid Vitamin D and C pushed painfully into the IV line.

Everywhere, doctors and nurses are run off their feet. Most of them have already had Covid. A friend messages to say dozens of infected health ministry officials are unable to get hospital beds. The country’s Covid-19 taskforce spokesman – whose unenviable job has been to sell the government’s handling of the pandemic – has also tested positive. He is one of thousands infected despite being fully vaccinated. My colleague Chandni Vasandani is another. She had her second Sinovac jab in March and suffers only minor symptoms, as do 13 family members. All, bar one, are at least partially vaccinated. Her diabetic boyfriend is not, however, and ends up in hospital where he is told he needs nine vials of Remdesevir.

The hospital is out of the drug, as are pharmacies across Jakarta. From my hospital bed I message a doctor I know who helps source six spare vials from a family that bought them for a sick relative. He either died or recovered; we don’t ask which. Only weeks earlier I wrote of desperate Indians pulling favours for life-saving drugs and I am now doing the same. But it feels good to focus on someone else. “Try not to think bad thoughts,” one nurse tells me. “It will only make your condition worse. Patients who worry end up sicker.” I know he is trying to help but it compounds my fears.

What to do in a health emergency is a question that has vexed past and present Indonesian correspondents. With Singapore closed, the last line of defence is medevac flights but it is a morbid and counterintuitive lottery, and never more so than during a pandemic. It can take up to a week, sometimes even longer, to secure an air ambulance and all the approvals required from both countries, and at the end of it a patient must be sufficiently stable to fly. Many don’t make it. In our case, thanks to the work of a small army of colleagues, friends, family and total strangers, it takes five days.

In hospital, I think often of the South Australian oil and gas executive, a 41-year-old Oxford scholar, father and former mayor who died in a Jakarta hospital last September of a Covid-related infection as his family tried to arrange a medical transfer to Australia. He is on my mind again as we wait in an ambulance with two nurses on the tarmac of Jakarta’s second airport while the medevac company scrambles to find a relief pilot for the one who has called in sick with Covid. We are to be transferred to the Royal Adelaide Hospital in one of numerous private medevacs to Australia that have occurred during the pandemic.

It feels like a minor miracle when we board the tiny plane, reunited finally with our little girl. The air ambulance is crammed with oxygen cylinders, our daughter dressed like a little Covid nurse and we look like ailing astronauts. But it is no joy flight. The doctors are confident Graham is recovering sufficiently to be able to sit up in the plane but I am told I will be transported by stretcher, catheterised and sedated in a hooded and fully enclosed plastic oxygen suit, unless I too can sit upright in it for nine hours without food or toilet.

There is enormous comfort in the gleaming halls and well-equipped rooms of the Royal Adelaide Hospital with its fastidious medical checks, care and professionalism. I get the occasional feeling I am an oddity, even in the infectious diseases ward, where I end up with some complications days after being cleared for medi-hotel quarantine. Some staff stop to watch as I am wheeled out of my room accompanied by an ever-present security guard for more scans. Our biggest concern is who will care for our daughter in quarantine if we have to remain in hospital. Like many in Australia at the time, our family is only partially vaccinated. We can count on a few hands the people we know who have had both jabs and only one, with three kids of her own, we can call on to help.

She flies from Sydney to Adelaide without hesitation, an extraordinary act of selflessness that in the end proves unnecessary. Graham and our daughter are cleared for quarantine with intense medical supervision, including five phone consultations a day, constant oxygen and temperature reads. I am not far behind, though it will be another 10 days before I can do more than walk from the bed to the bathroom.

It seems remarkable that two months later we are back to almost full health, bar a mental fog that sometimes leaves me struggling for words and names. The dreaded long Covid, where post-viral fatigue and other symptoms can plague for months those who might have previously suffered only the mildest infection, seems to have passed us by.

In Indonesia, the nightmare eight-week surge that claimed tens of thousands of lives has abated in the wealthier areas at least, though test positivity rates still fluctuate between 30 and a ludicrous 100 per cent in other parts of the country. Hundreds of Jakarta schools are preparing to reopen, a few days a week, for the first time since March 2020. The city claims to have fully vaccinated 62 per cent of its targeted population, though the rest of the country lags far behind. The lowest rates are, predictably, in the poorest provinces such as Papua and Aceh.

The good news is that Indonesia has now fully vaccinated 34 million people, five times that of Australia. The bad is that some politicians and bureaucrats are already nudging health workers down the queue in the rush for a third booster shot while 140 million eligible Indonesians await their first jab. The country rightly protests the grotesque inequity that has seen rich nations hoard the lion’s share of global vaccines, yet the same injustice is playing out within its borders. Until both scenarios change, our largest and most important neighbour remains at considerable risk.

Amanda Hodge is the Southeast Asia correspondent for The Australian

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout