Midlife athletes: how do they stay fit?

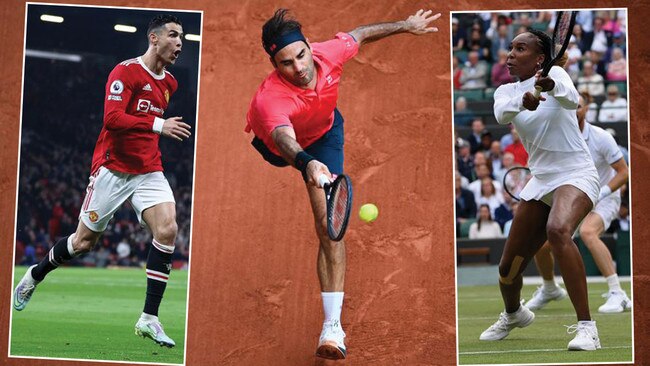

From the football pitch to the tennis courts, great players have more staying power than ever.

Athletes have always been expected to retire gracefully as they approach their thirties, with even world-beaters unlikely to override the decline in prowess that comes with ageing. But not the present crop of super-ages, who seem to perform better the older they get, maintaining their elite status well beyond the age that was once considered to be the sporting prime.

At a sprightly 35 and 36 respectively, Novak Djokovic and Rafael Nadal are still showing younger rivals how it should be done at Wimbledon while the former world No 1 Roger Federer has outlined his intention to return in 2023 at the age of 41. In football, a game in which players were once routinely sidelined with injury by their thirties, the all-time top goalscorer Cristiano Ronaldo has reportedly told Manchester United that he wants to leave the club, driven by the desire to play in the Champions League next season at the age of 37. Meanwhile, AC Milan are apparently trying to retain the services of Zlatan Ibrahimovic, despite him being 40. And in cricket, 39-year-old James Anderson, England’s most prolific wicket-taker, has no qualms about playing on as a fast bowler in Test matches.

It’s not just men who are defying the odds. After taking a career break to have two children, Tatjana Maria, 34, had a dream week at Wimbledon (she plays fellow German Jule Niemeier, 22, in the quarter-finals on Tuesday).

Venus Williams, 42, didn’t go as far, but had an impressive tournament alongside Jamie Murray in the doubles.

What’s more remarkable is that these athletes are competing in sports that require not just endurance, which is known to peak later in life, but strength, speed and skill.

“Top athletes have always been committed and resilient,” says Jamie McPhee, professor of musculoskeletal physiology at Manchester Metropolitan University Institute of Sport and an expert in the effects of ageing on athletic performance. “But there is a new level, supported by science and other resources, that means these athletes can prolong their careers at the top.” Here’s how:

PREHAB AND REHAB

Optimising athlete health is key to preserving performance, and much of it comes down to injury prevention and recovery practices. These days, physiotherapist-designed warm-ups are tailored to individuals and focus on muscle activation and fascial release using foam rollers and rubber exercise bands.

“Sports science support has come on massively in this regard in the last two to three decades,” McPhee says. “If you can prevent injuries in the first place, or manage them appropriately, you can add a few years to an athletic career, and the younger in someone’s life these measures are adopted, the higher the threshold for maintaining top performances is raised.”

No stone is left unturned. Biomechanists analyse technique using force plates – a system that measures the physical impact of an athlete’s movements – and suggest tiny adjustments that can make a difference to injury outcomes. If disaster still strikes, physios are immediately in attendance, and devices such as anti-gravity treadmills allow sports people to quickly resume training by reducing the force with which they hit the ground.

“Every aspect of an athlete’s life is now geared towards injury prevention in a holistic way,” McPhee says. “I know of footballers who bring in experts to advise where the windows in their houses should be to optimise sleep because they know that a lack of sleep and fatigue can lead to the accumulation of injuries.”

RECOVERY METHODS

A post-workout massage was once the most an athlete could expect in terms of recovery aids. In 2022 massage remains important but it is just one of an armoury of tools now available for athletes. From foam rollers and compression clothing – tight-fitting elasticated socks and sleeves recently shown to reduce perceptions of muscle soreness after exercise – to inflatable pneumatic compression leggings and handheld massage guns, recovery has become a science in itself.

“For older athletes, knowing how to avoid accumulating fatigue and optimising recovery is essential for maintaining performance and reducing injury risk,” McPhee says. “There’s a much better understanding of the importance of recovery for athletes, beyond getting the basics of good nutrition and sleep patterns.” Cryotherapy, in the form of ice baths or ice chambers, is widely used – Nadal and Andy Murray are fans. Chilled mostly by liquid nitrogen, ice chambers subject the body to temperatures to as low as -160C which is believed to speed recovery and reduce inflammation in soft-tissue injuries. “The idea is that the cold temperatures shock the body into changing blood flow,” McPhee says. “Nutrients and oxygen delivery to muscles is supposedly enhanced.”

NUTRITION

There remains plenty of pseudoscience in the world of sports nutrition, but elite sport has come a long way since steak and raw eggs were considered the best performance-enhancing foods, with particular relevance for older athletes.

“The ageing process is accompanied by physiological changes that can affect exercise capacity, muscle mass and strength,” says the sports nutritionist Anita Bean, author of The Complete Guide to Sports Nutrition. “But a combination of better training, recovery and nutrition practices means that top athletes now eat to train ‘smarter’, meaning they can maintain high fitness levels even after age 40.”

Added to the everyday practicalities of balancing food and fluid intake for optimal returns before, during and after training, specific interventions can help ageing athletes to stay in the game. “As you get older, your body is less able to respond to the anabolic, or building, effects of dietary protein, which means it’s harder for it to turn protein into muscle,” Bean says. “This is called anabolic resistance and it is now known that older athletes need relatively more protein, around 1.5g per kilogram of their body weight per day, or 40g per meal.”

Timing of protein consumption also matters. “Studies have shown that consuming protein immediately after intense training helps to compensate for anabolic resistance of ageing, so building new muscle. And having a high-protein snack, such as Greek yoghurt, before bed has been shown to maximise the effects of resistance exercise and help with protein synthesis in older athletes,” she says.

Meanwhile, supplements such as tart cherry juice and beetroot shots have been shown to enhance recovery after intense training, and vitamin C supplementation has been shown to help older people to retain muscle mass.

PSYCHOLOGY

A rarity in the 1980s and 1990s, sports psychologists are now available to almost every elite athlete to help to develop traits that are important for sports longevity. Dr Josephine Perry, a consultant sports psychologist and the author of The Ten Pillars of Success: Secret Strategies of High Achievers (Allen & Unwin), says older athletes are often more pragmatic about sporting success as well as being more emotionally consistent and better able to keep negative thoughts at bay when competing.

“Broadly speaking, there are different mindsets, with younger athletes being mostly ego-driven, focusing purely on results and times and how they look, which can trigger a lot of unwanted stress and anxiety,” she says. “With older athletes, the mindset shifts to one of mastery or being brilliant at what they do, which is much more stable and has better outcomes.” In practice this translates as striving to be the best they can be, maximising the time that they can continue to compete at the top level. “I spend my life trying to teach this to young athletes,” she says. “It comes naturally to many older athletes.”

She mentions a conversation she had recently with Sarah Storey, Britain’s most successful Paralympic athlete, who won the cycling individual pursuit at the Tokyo Games aged 43, her 17th Paralympic gold and 40th world title. Storey, who has two children, has said she has no plans to stop competing. “When I asked her when she will retire, she responded, ‘When I can’t see any way of getting better.’ And that is typical of many older elite competitors who are driven not by winning everything but by being the best they can possibly be for as long as they can.”

STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING

Ageing affects sports performance in many ways, but the biggest impact is the downturn in muscle repair and rejuvenation coupled with a gradual loss of total muscle mass, a process called sarcopenia, that occurs after the age of 35. Collectively, this has the potential to reduce power, strength and technique and was traditionally why athletes in sports that rely on these attributes, such as tennis, football and sprinting, had earlier career peaks than endurance runners and cyclists. As sports monitoring has improved, so more sophisticated strength and conditioning programs tailored to an athlete’s needs have helped to offset the decline.

“Strength and conditioning has become really specific to the type of sport and the individual,” McPhee says. “It is geared not just towards gaining muscle, but to improving fatigue resistance, the goal being to help an athlete train so that they can adapt and improve in their thirties and even forties.”

Yes, they lift weights and do press-ups, but rather than progressively increasing how much they can bench press, for example, an athlete will focus on correcting muscle imbalances while improving quality and range of movement, balance and flexibility. “They will work on agility, and Ronaldo is big on maintaining sprint pace, disproving the belief it declines with age,” McPhee says. “At the highest level it will be very, very personalised stuff and comes down to maintaining that perfect machinery.”

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout