Legacy of native species loss

Australia’s record for extinction of native bird and animal species is getting worse.

Eric Zillmann’s eyes twinkle as he recalls how he spotted a pair of paradise parrots 86 years ago when, as a young station hand, he was riding his horse on a property near the southeast Queensland town of Gin Gin. “I remember them still, feeding on the ground and flying up into trees,” the 98-year-old says from his Bundaberg retirement village home.

“I could see the lovely colours on the birds. We’d ride up there to dip the cattle once a month and I’d see them every time.”

He observed the parrots for a further three years until 1938, when he left the area. Zillmann was likely the last person to see a paradise parrot and is the only individual alive to have had the good fortune to lay eyes on one.

One of Australia’s most beautiful animals, the paradise parrot is the only bird on the nation’s mainland to become extinct. It was thought to have been lost before the turn of the 19th century but was rediscovered in 1921 near Gayndah, not far from Gin Gin, by pastoralist Cyril Jerrard.

Ornithologists this year are marking the 100th anniversary of what was regarded at the time as a natural history find of great significance for the country. The joy was short-lived. Jerrard photographed the parrot for the first time; his grainy images of birds at a nest are the only ones existing. Parrots were seen sporadically for a while longer, until Zillmann’s encounters. Then the paradise parrot was lost again, this time forever.

Now, the fate of the paradise parrot’s closest relative, the equally resplendent golden-shouldered parrot, is in the balance. The two species share the unusual habit of digging tunnels in termite mounds to build nests. (The mound housing the nest that Jerrard famously photographed remained intact until collapsing a half-century later in 1974.) Both birds favour lightly wooded country with a plentiful supply of grass seed.

The paradise parrot was restricted to a small area of southern Queensland. Its demise followed the extensive modification of its habitat for cattle pasture and the widespread destruction of termite mounds, which were valued as a base for tennis court construction.

The golden-shouldered parrot is similarly confined to a small area of woodland but farther north, in southern Cape York Peninsula. A 125,000ha cattle station, Artemis, is the epicentre of the parrot’s territory. Fourth-generation grazier Susan Shepherd has been observing golden-shouldered parrots on the property for 30 years.

In that time, Shepherd says, the parrot population has crashed from as many as 2000 to 50 today. In woodland not far from the station homestead, she points to a small hole in a “witch’s hat” termite mound a metre above the ground that leads to a parrot nesting chamber used last season. “Once I’d find 100 nests or more in a season,” she says. “Now it’s a struggle to find three or four. Birds are gone from many places where you could find them before.”

Shepherd is battling to protect her 50 parrots and hopes to increase the population. Cattle grazing has reduced the supply of seed favoured by the birds; seed now is purchased and left out for them.

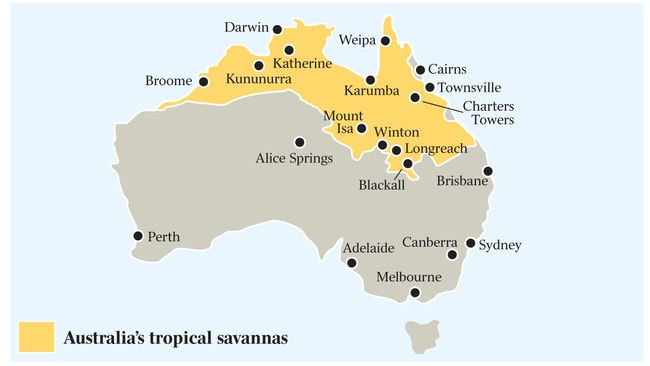

A bigger challenge facing the parrots is one afflicting the vast tropical savanna woodlands that cover the northern quarter of Australia: the mismanagement of fire on an epic scale.

On Cape York, traditional light burning by Indigenous people was replaced by tighter restrictions on fire after European settlement. Open grassy areas were invaded by thick scrub not suitable for parrots and other woodland animals. The vegetation provides cover for feral cats, butcherbirds and other predators that kill golden-shouldered parrots. Some cats have learned how to track down and pillage the termite mound nests.

Bush Heritage Australia estimates the total surviving parrot population is as few as 780. The conservation group is helping Shepherd to rehabilitate Artemis. A 2000ha plot has been destocked and other areas are being cleared or thinned to restore open woodlands and reduce cover for predators. A new fire regime will be implemented and feral pests controlled. “Hopefully there’s a brighter future,” Shepherd says.

Elsewhere across the savanna belt, the mismanagement of fire is wreaking havoc in a different way. The horrendous bushfires of the 2019-20 summer in southeastern Australia captured the world’s attention, but massive and frequent fires of great intensity are a common feature of the tropical north.

Data collected through satellite imagery estimates 20 per cent of the 1.9 million square kilometres of savanna woodland in northern Australia burns each year. Savanna fires account for 70 per cent of the area burned in Australia annually; most of the rest is in the arid inland, with just 2 per cent in the country’s heavily populated southeast.

Mismanagement of fire in Australia’s savanna – the most extensive area of that landscape in the world – has far-reaching consequences for biodiversity. Several threatened species have been wiped out in the escarpments of the Borroloola region of the Northern Territory by fires lit by landholders. Among them was the entire NT population of a rare small songbird, the carpentarian grasswren.

An environmental consultant working in the area, who asked not to be identified, says: “Planes went up each season dropping hundreds of incendiary devices across huge areas. Everything burned. Pockets of vegetation high up in the escarpments that normally provide refuge for animals from fire were incinerated. It’s a moonscape.”

Charles Darwin University researchers confirm that recent surveys have failed to find rare animals known previously from the region.

While natural open woodland in some parts of the savanna belt, like Artemis on Cape York, is replaced by thick vegetation because fire is restricted, elsewhere fires for pasture improvement or control burns are lit too often or at the wrong time of year, resulting in widespread torching of the countryside. The most fire-prone part of the most fire-prone continent is poorly managed.

Northern Australia’s 60,000-year history of fire management by Indigenous people centred on fires lit throughout the year, particularly early in the dry season. Many fires today occur late in the dry season, when they are more intense because of greater fuel loads and higher temperatures.

CDU professor Alan Andersen says: “Recent decades have witnessed precipitous declines in populations of small mammals across northern Australia and changed fire regimes are implicated as an important factor.” For instance, the brush-tailed rabbit-rat has been pushed to the brink of extinction on the NT mainland.

Andersen says fire is “not inherently bad”; savanna is well adapted to fire every two to five years. The severity and frequency of fire is the issue. Mammals and reptiles are vulnerable to increased predation by feral cats when protective vegetation is removed.

That’s an ironic variation of the cat threat to golden-shouldered parrots: fire mismanagement threatens the survival of native wildlife in different areas in different circumstances.

Australia is the only country to include emissions from savanna fires in its national greenhouse gas accounts, with landholders earning carbon credits by reducing emissions through changed fire management. The program rewards burning early in the dry season to reduce the frequency of hot fires.

The scheme has had limited impacts on curbing the extent and intensity of damaging fires, however, and perversely creates new hurdles.

Over at Artemis, carbon credits are an important money earner for Shepherd, like many landholders, but they mean she can’t burn the hot fires late in the year needed to restore open woodlands. “It’s a big bad circle that keeps going round and round,” Shepherd says.

Large areas of savanna are under public stewardship. Kakadu in the NT, managed jointly by traditional owners and Parks Australia, is widely regarded as the jewel in the crown of Australia’s national park estate. Satellite images show a third of Kakadu’s 20,000sq km burns annually.

CDU ecologist Stephen Garnett, who has conducted detailed research on fire impacts, says of Kakadu National Park: “There is a legacy of loss in Kakadu from very poor fire management that’s extended over many years. A whole lot of animals are gone.”

Another songbird, the white-throated grasswren, is found nowhere in the world but atop the sandstone cliffs of Kadadu. The bird’s population was estimated to be as high as 182,000 in 1992; today it is about 1100, perhaps fewer. Says Garnett: “It’s going to take years and a good deal of investment to turn things around. It’s been a big wet season and I fear we’re going to see big fires later in the year.”

Leading fire research scientists John Woinarski and Sarah Legge, referring to the savanna generally, conclude: “There is evidence that many species of birds and other vertebrates and plants are declining across substantial parts of this region and that current fire regimes are contributing to that decline, and in some cases are the major driver of it.”

Meanwhile, introduced grasses such as buffel and gamba are running riot across the savanna as well as over much of inland Australia. Prolific growth of exotic grasses is fuelling the intensity of fires and allowing them to reach previously protected areas of spinifex and other native vegetation.

The CSIRO’s Historical Records of Australian Science has published an essay by James Cook University historian Russell McGregor marking the 100th anniversary of the paradise parrot’s rediscovery. McGregor says: “Rediscovery of the paradise parrot in 1921 failed to inspire sufficient action to save the species. We can’t afford similar inaction towards endangered species today. Experts had scant scientific information on wildlife extinctions 100 years ago and even less on how to avert them. That is no longer the case.”

Greg Roberts is a Sunshine Coast-based journalist.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout