Kelvin Ho Akin Atelier Sydney Modern Gallery Shop

Akin Atelier founder Kelvin Ho is fast becoming one of Australia’s most in-demand architects.

The steps leading up to the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s original south building are cut from Sydney Basin sandstone, which forms the bedrock of much of the city. Across the course of 122 years, the dusky tint of the stone has taken on a straw-coloured patina; its grainy texture has been swept by wind and pounded by foot to form a rhythmic surface that is slightly chalky to touch.

It’s a surface Kelvin Ho is intimately familiar with, because the architect spent much of his childhood circumnavigating these very steps on his skateboard.

“As a skateboarder, you’re always interacting with the finer grains and elements of the city. There’s a real tactile quality to it, and I love the way you get this feel for the way materials morph and change over time,” says Ho. He nods to the brass handrails, which run up either side of the sandstone steps and frame the gallery’s neoclassical facade. “You can see where the shiny brass transitions into this dull green colour, from people holding onto it.”

Exploring the city on four polyurethane wheels has long provided Ho with a unique understanding of materials that make up urban environments, and how these materials can be applied to (or inform) the contemporary projects that Akin Atelier, the hip Sydney-based architecture, interior and spatial design studio he founded as a 26-year-old in 2005, takes on.

But this sense of perspective feels particularly profound — even a little full-circle — in the context of Ho’s most experimental and technical project to date: the Gallery Shop inside the The Art Gallery of New South Wales’s brand new $344m Sydney Modern building.

Four years in the making, it has been visited by the public since December last year, when the expansive 7000sq m building designed by globally renowned Japanese firm SANAA was officially opened.

Yet this is the first interview Ho has given about the project.

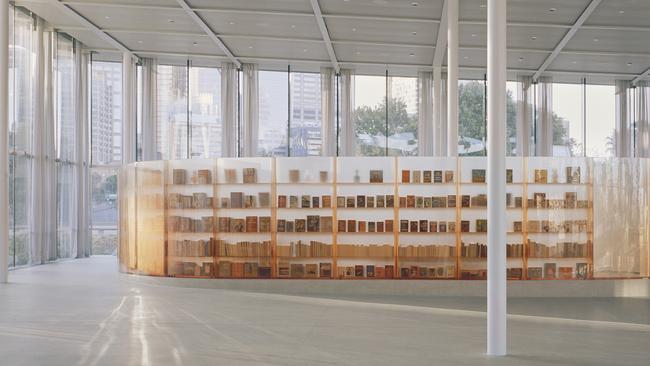

“It’s a relatively small project within the scale of the entire gallery – it’s about 140sq m inside this enormous building,” reveals the architect. “But it’s a space within a space right at the front door, and it’s also a huge part of the gallery’s commercial revenue stream, so it needed to be really functional while having its own identity.

In contrast to the sleek minimalism of SANAA’s design, Ho’s pitch to the gallery was inspired by those parts of the institution’s exterior that you can physically touch and interact with.

“Because touch and picking things up is such a big part of any retail space, we felt like the gallery store had to be the equivalent of those handrails, and the steps. Because in a typical gallery, you are distanced from the works and the sculptures – you can’t really touch them,” he says.

“But that’s what the store is about. We thought that was a really interesting narrative, and we wanted to find a material that had that interesting tactility.”

The material Ho and his team landed on required the gallery to take “a huge leap of faith”.

“Resin was my obsession as a student and we’ve done a few projects using resin at the studio, so it’s really been an interesting part of my architectural career,” Ho tells The Australian. “It’s malleable and translucent. But traditionally, it’s used to craft smaller objects, like homewares or surfboards.”

Ho, meanwhile, wanted to make the perimeter of the store — which is made up of 29 units that also function as 2.4m-tall bookshelves – from bio-resin, which is a solvent-free, low-viscosity form of the substance. A handful of makers told the team it wasn’t possible, and just as Ho himself was doubting the feasibility of his vision, a serendipitous conversation with surfboard shaper and multidisciplinary designer Hayden Cox, of Haydenshapes, set the original plan in motion.

“We worked closely with Hayden as a key collaborator, and the UTS structural engineering labs to test everything, because as a material that hadn’t been used before on this scale, they had to be cast in a monolithic way, and early on, we’d try and the whole thing would just explode.”

The research and development phase was undertaken in the Mona Vale factory Cox manufactures his surfboards in on Sydney’s Northern Beaches – the panels would be crafted from a bio-resin Cox developed exclusively for the project, which consists of 26 per cent biological material. But when it came to casting, pouring and finishing the units, the team found they had bitten off more than they could chew.

“Hayden managed to find a landlord that had two empty factories nearby, so we basically had to set up these two custom facilities,” Ho says.

After about two years of trial and error, Ho and Cox had their 29 resin panels, each weighing close to 500kg. In situ, the structure looks almost weightless, as if it’s floating above the foyer’s concrete floor. Its frame transitions from dusky pink to orange, another nod to the layered texture of those sandstone steps.

This ombre-like appearance was achieved by hand-pouring layers of bio-resin into moulds custom-designed by the Haydenshapes Factory and Akin Atelier for 109 consecutive days.

“There were times where I was really doubting our ability to pull it off,” says Ho with a chuckle.

He credits the fearlessness of associate Alexandra Holman, who was the project designer, as well as the openness of AGNSW itself, as helping him keep the faith. “I think the gallery saw potential in the unconventional use of materiality, the use of an interesting local fabricator, and the fact this almost transcends traditional retail design to become more like an art installation itself.”

Ho says collaboration was a huge part of the Gallery Store project. In this sense, he views it as an extension of a career-long practice that spans retail, hospitality and residential design – defined by an intelligent application of materials, colour and Akin’s cool, unfussy aesthetic, each interior has come to fruition through collaborative dialogue between clients, makers and the studio itself.

The architect’s appetite for cross-disciplinary discussion, and the boundary-pushing creative outcomes it fuels, means that Akin Atelier has become one of the country’s most in-demand architectural studios, especially among a cohort of highly successful, creatively minded business people.

Ho has designed over 20 hospitality venues for Justin Hemmes, Merivale chief executive. Next month, the duo will add another finished project to that list, when Hemmes’s reimagined Lorne Hotel, which he bought for $38m in 2021, opens on Victoria’s Great Ocean Rd, complete with an Akin-designed interior.

Hemmes tells The Australian that since working on his Potts Point institution, Mr G’s, together for the first time in 2011, Ho has become not just a collaborator, but “one of my dearest friends”.

“Every job we work on together is a wonderful journey,” Hemmes says. “He has an incredible mind and is a man of many layers, all of which pair brilliantly with his cool, calm demeanour.”

Qantas, the luxury Maldivian resort Amilla Fushi and directional fashion retailers like Camilla and Marc, Incu and Poho Flowers have also engaged Akin’s zeitgeist. Another of Ho’s longstanding clients is the sustainable Australian fashion brand bassike.

“In my experience, Kelvin is a man of few words, yet he is always actively listening and thinking, which is how he inherently understands each project and collaboration,” offers bassike’s co-founder and creative director, Deborah Sams.

Testimonials of this nature aren’t scarce when Ho’s name comes up in conversation. In fact a glowing set of references from collaborators helped Akin Atelier secure the Gallery Store contract. It was a considerably high-stakes gig – Sydney Modern is the city’s most significant arts opening since the Opera House – and Ho, Cox and their teams didn’t exactly play it safe. But today, the store’s resin frame is one of the gallery’s most arresting features.

“When I go in there, I can see the intrigue that the gallery store provides the guests with. People walk up to it and they’re like, ‘what is it?’ They want to touch it; they want to understand it. Because it’s like something they’ve never seen before,” comments Ho. “For me, that is the most lovely feeling.”

From a wave pool on the outskirts of Sydney to more cutting-edge industry projects with sustainability front of mind, Ho’s reputation as an architect with a truly singular eye is only set to grow.

Take it from Hemmes: “Kelvin’s worldly view, and the depth and diversity of his creativity, never ceases to amaze me.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout