Just how much has changed for female Olympians heading to the Games?

As she prepares for her fourth Olympics, the Gold medal-winning swimmer Bronte Campbell reflects how female athletes are perceived in the century since the Games were last held in Paris.

It’s the eve of Paris ’24 and the Games are about to begin. Competitors gather, dreams are yet to be shattered and the world prepares for the biggest show of human achievement.

The Olympics are the best display of what our bodies are capable of, bodies honed to perfection by athletes with single-minded determination. So reads the Olympic motto: Citius, Altius, Fortius. Faster, Higher, Stronger.

Except I’m not describing the present day. This same scene, with the same drama and emotions, has played out before. A century ago, at the Paris 1924 Olympic Games, around 3,000 athletes gathered to see how they measured up against the best in the world. Of that cohort, just five per cent were female. And none of those women were Australian.

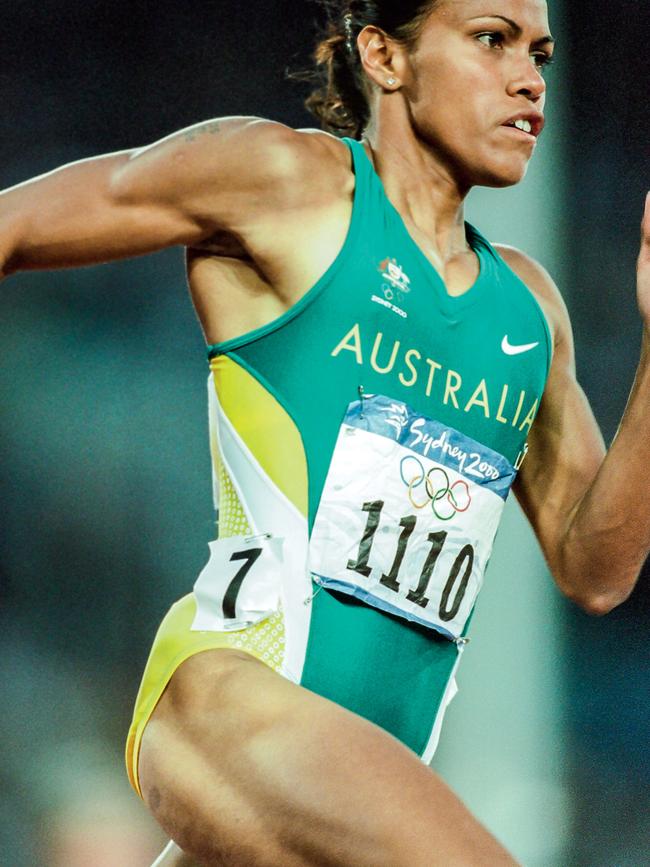

Sport is a microcosm of society. It reflects what we value, who we admire, what stories and mythologies we choose as messages for future generations. When we talk about sport, we often talk about Games past and moments remembered. (Who can forget Cathy Freeman’s 400-metre final at Sydney 2000? Or Kieran Perkins winning from lane eight in Atlanta 1996?) But the more interesting question is: what does sport tell us about ourselves?

This query sent me down the rabbit hole of looking at the 1924 Olympics versus the Games now on our doorstep. Exactly 100 years have passed, so how has society changed and how is this reflected in the sport and people we watch and admire? Being both female and an athlete, these topics are always forefront in my mind: how were female bodies perceived, what was and wasn’t allowed, and what echoes remain today? It is not lost on me that if I was competing 100 years ago, I wouldn’t be in Paris wearing the green and gold at all.

At the 1924 Paris Games, women were allowed to compete in fencing, diving, swimming and tennis. The major concern at the time was swimsuits; not how they impacted performance but how they could contribute to ‘public nudity’. As such women wore long woollen bathers, which created a lot of drag in the pool, but at least covered up their bodies.

What is also clear to see is how art represented femininity at the time. The 1925 novel The Great Gatsby had the dainty, flighty and enigmatic female character of Daisy Buchanan and her iconic line: “The best thing a girl can be in this world is a beautiful little fool.” The message was clear: beauty was preferable to intellect and physicality was reduced to appearance.

Of course, beauty has always been its own sort of power, often the only power women could access that might change the course of their life. But who gatekeeps what is considered beautiful? In the 1920s, where women were described as desirable for being, soft, gentle, meek and dainty, is it any wonder that Australia fielded no female Olympians at the 1924 Games in Paris?

“There is still a desired aesthetic and rhetoric of exercise being a way to enhance the way you look rather than the way you live”

One hundred years can feel like a long-distant past; of course we know better now. But history has a way of lingering and society changes slowly. In my own adolescence, as I was beginning to feel body conscious, the biggest show in Australia was The O.C., which starred a Daisy Buchanan-esque character called Marissa, played by Mischa Barton. Remember, in the early 2000s we were reeling from the years of heroin chic and becoming fully immersed in a world of diet culture.

Meanwhile, I was already pushing my body up and down the pool every day. I was already in the gym doing weighted chin-ups. I was already on the road that has since led me to three Olympics, and hopefully a fourth. As a teenager, I remember resigning myself to the fact that the path I had chosen might make me undesirable. That I was sacrificing so-called traditional standards of beauty, as seen in television shows and at the movies, for my dream. That I, with my already muscular and broadening shoulders, didn’t fit the mould. There are many sacrifices in sport, but this was not one I had anticipated.

At least I had a vision from the women who had gone before me. If I couldn’t be ‘beautiful’, like Marissa on The O.C., at least I could be like the Olympians. I could be like Dawn Fraser and Susie O’Neill, whose feats in the pool live on in swimming legend. I could know what it was to raise my arms in triumph at the end of a race and stand atop a podium with Olympic rings in the background.

In the 20 years that have passed since I was a young girl, the explosion of fitness influencers on Instagram has changed the beauty standards that I grew up with yet again. However, there is still a narrow window of what is celebrated. (Strong glutes are fine, but don’t make your quads too big!) There is still a desired aesthetic and a rhetoric of exercise being a way to enhance the way you look rather than the way you live.

My favourite thing about the Olympic Village at any Games is the dining hall. Here, 10,000 athletes gather every day. There are seven-foot-tall volleyballers, strong and powerful weightlifters, five-foot-high gymnasts, swimmers with broad shoulders, cyclists who can leg press 300 kilograms. Whatever body shape or size you can imagine is there, honed to be as effective as possible at their chosen sport. Every body at its pinnacle performance, every body looking entirely different.

A Cambridge University study from the 2016 Rio Olympics found that words used to describe female Olympians focused disproportionately on clothing and personal lives, on aesthetics rather than athletics. That ‘female’ was used as a qualifier: the female golfer, the female swimmer, the female champion as opposed to the ‘male’ which was assumed. (The golfer, the swimmer, the champion.) At those same Olympics, I achieved my lifetime goal. I got to stand on top of the podium as part of a world record breaking relay team. I got to hear the Australian anthem echo through a stadium and watch our flag wave around the crowd. Something I’d dreamed of for years, something that would have been out of my grasp in earlier centuries.

In just a few short weeks, Australia will send its highest proportion of female athletes to the Paris Olympics. How many echoes of 1924 remain is up to us to decide when it comes to how we view and talk about these women, myself included. Words have power and we hold the responsibility for our choices.

So, as you sit down to watch these Paris Games, if you’re struggling to think of words to describe the female competitors, here’s one you can use: athletes.

This article appears in the July issue of Vogue Australia, on sale now.