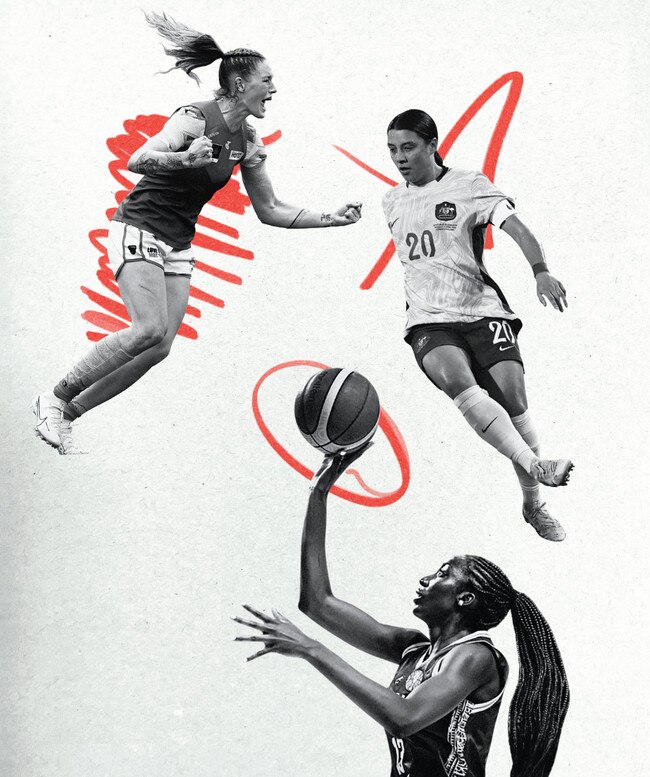

How women’s sport got bigger than ever

With the Matildas among the favourites to win at the upcoming FIFA Women’s World Cup and more people tuning in to women’s sport than ever before, female athletes are at the top of their game. But while great strides have been made, there remains plenty of work to do before it’s truly a level playing field.

This winter, Australia and New Zealand will co-host the ninth edition of the FIFA Women’s World Cup. It is going to be huge. That may seem a presumptuous statement, but it’s true. Ever since FIFA president Gianni Infantino confirmed the winners of the bid in June 2020, it has become increasingly undeniable that the World Cup will be huge. Not just huge, but enormous, massive.

For the Australian women’s national team, affectionately dubbed the Matildas, it is both a pressure and a privilege to host a World Cup. Winning on home soil is an opportunity typically afforded only once in a player’s career. Football Australia needed to find a coach who could make this a plausible reality.

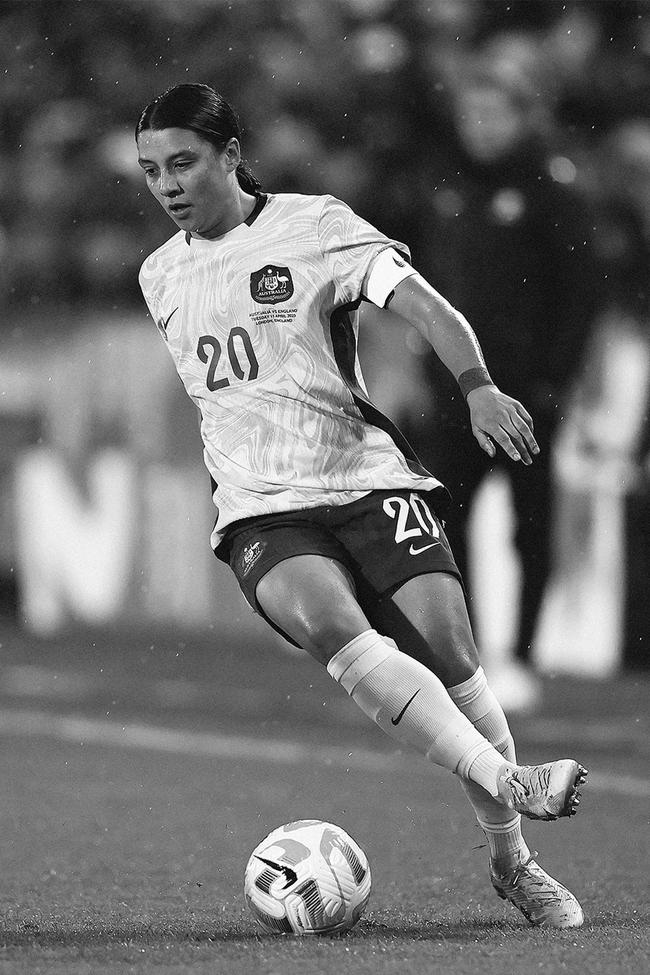

Tony Gustavsson was appointed in September 2020 and inherited some of the best players in the world. These included Australia’s most prolific goal scorer of all time and two-time Ballon D’Or finalist Sam Kerr; two-time UEFA Women’s Champion League winner Ellie Carpenter; and former Asian Women’s Footballer of the Year Caitlin Foord. Gustavsson needed to figure out how to harness their talent while building depth across the squad, both for now and the future. All of this, in less than three years, and with a pandemic thrown in.

It was never going to be easy. There were the early drubbings the team received at the hands of European opposition; disappointing home outings against current world champions America and Olympic gold medallists Canada; and, perhaps most devastating, a shock early exit from the Asian Cup many thought Australia would win.

These losses have come with silver linings in the form of newly blooded stars. Since Gustavsson’s arrival, 19 players have debuted for Australia—as many debuts as from the three coaches who preceded him. Some of these names, such as young guns Kyra Cooney-Cross and Cortnee Vine, are now mainstays likely to feature on the list of 23 players selected for the tournament.

Now, a matter of weeks out from kick off and on a solid run of form, there’s a quiet optimism brewing among dedicated and casual fans alike. The Matildas could really win this. In the past six months, they have beaten Sweden, the world’s No.2. And they didn’t just win—they thrashed them 4–0, their biggest ever score margin over a top five team. The Matildas ended European champions England’s 30-match undefeated streak, on opposition territory no less. They turned their 7–0 loss against European heavyweights Spain in 2022 into a 3–1 win.

The fans have not wavered in their belief (one of Gutsavsson’s favourite words). They broke the record for the most-watched women’s sporting side during the Tokyo Olympics, when 2.32 million people tuned in to see them play Sweden in the semi-final. Although losing and placing fourth, it was the furthest Australia had gone at the Games. Again, at friendly matches, fans turned out in droves, breaking Sydney and Newcastle’s previous crowd records. Leading into the World Cup, tickets to Australia’s group stage games have been snapped up, with the opening match against Ireland moved to the 80,000- seat Stadium Australia to accommodate demand.

These are just local examples demonstrating the dramatic rise in popularity of women’s football. A little more than a year ago, Barcelona’s women’s side broke the global record for women’s football attendance with a home game win over rivals Real Madrid. A total of 91,553 people attended the Camp Nou to see the Spanish titans claim victory.

Barca would pip their own record only a month later in their Champions League semi-final against Wolfsburg. Both matches overtook the previous long-standing record set at the 1999 FIFA Women’s World Cup final in California. Many may know this moment not for the scoreline between US and China, but by the now legendary image of Brandi Chastain celebrating her winning penalty, sliding on her knees, shirt in hand, roaring with victory. (The score was 0–0, won 5–4 on penalties.)

And this enthusiasm is not just for football. Women’s sport is selling out across the board. In 2020, the ICC Women’s T20 World Cup final between Australia and India packed out the Melbourne Cricket Ground. The crowd of 86,174 was a record turnout for women’s sport in Australia and the highest for women’s cricket in the world.

In 2017, round one of the AFLW saw fans locked out of a game between Carlton and Collingwood at Melbourne’s Ikon Park after it reached capacity. More than one million people have since attended a match in the league.

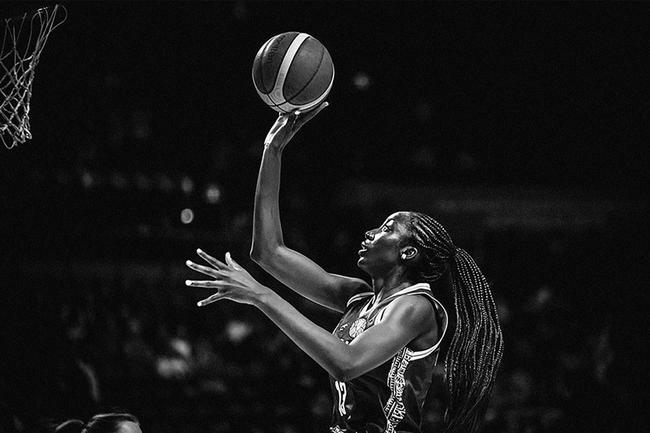

The 2022 edition of the FIBA Women’s Basketball World Cup, held in Sydney, was the most attended in the tournament’s history. Australians turned up for the Opals bronze-medal win, but it was the roars of support for China in their final against the US that highlighted the immense power of Australia’s cultural diasporas during global events.

Last year, Fox Sports revealed that women’s sport is more popular than ever. Some 70 per cent of viewers across its channels said they were watching more female codes than before, with two-thirds of the Foxtel audience now tuning in to women’s games, a trend driven by cricket, netball and AFLW. It’s not just women watching, either; two thirds of viewers are male, with 72 per cent of men watching women’s sport.

And it’s a trend that shows no sign of easing. The 2019 FIFA Women’s World Cup was the most viewed in the tournament’s history, with a total audience reach of 1.12 billion. Australia’s gritty comeback over long-term rivals Brazil boasted the seventh biggest global audience. This edition, FIFA is hoping to reach more than two billion viewers world wide.

The popularity of women’s sports on screens is closely connected to there being more women’s sport available to watch. It wasn’t that long ago that fans of women’s competitions had to make do with a select few games being broadcast per competition. Now, it is unusual for broadcasting deals to not encompass entire fixtures or competitions—a huge opportunity for women’s sport as streaming becomes the new normal.

That the Matildas are among the favourites is a bonus for Australians at the 2023 FIFA World Cup. Regardless of how they perform, eyes will be on screens, bums on seats and hearts in mouths as people follow along here and afar. The impact of the tournament extends far beyond that one month starting on July 20.

“That’s why this Women’s World Cup is so important,” says Sarai Bareman, inaugural chief women’s football officer at FIFA. “It’s about a lot more than just what’s happening on the pitch and who in the end will lift the trophy. There’s a lot of spin-off effects.”

Morocco’s national team is an example of this in action. Bareman outlines how in 2019, the president of the Royal Moroccan Football Federation, Fouzi Lekjaa, attended the Women’s World Cup in France. “He sat in a massively packed, full stadium with incredible atmosphere and at the final he saw how huge it was,” Bareman says. “He saw the commercial activations that were going on, the passion of the fans. And I think, most importantly, he saw how beautiful the game was. How brilliant and skilful the athletes were.”

Lekjaa went home and invested in women’s football. He invested in the players, coaches and infrastructure. Morocco would go on to host the continental tournament, the 2022 African Cup of Nations, finishing as runners-up and consequentially qualifying for the World Cup. They are one of eight countries who will debut at the Women’s World Cup this year, and the first team from an Arab nation to feature.

The impact seen in Morocco is what Bareman calls the “the Women’s World Cup effect”. While the magic of the event is powerful, it must be harnessed effectively. For one, it requires spending money—a sticky topic within women’s sports conversations. Inequities between men’s and women’s codes are often justified on the premise that women’s athletes, teams and leagues do not provide the same supple returns on investment as the men’s equivalents. Yet as Bareman points out, “The men’s game has been invested in massively for decades and decades. It didn’t get to where it is today without that investment. And we’ve got to give that same level of attention and investment to women’s football to see it reach the same heights.”

But there’s more to it than that. While the men’s game grew, women’s football was actively held back. In many cases, it was outright banned. In 1921, in the years following World War I, participation was booming around the world. In Australia, the first representative match was held in Brisbane for an estimated crowd of 10,000 people. That same year, the English Football Association (FA) banned women from playing on their pitches as a response to similarly popular charity matches held in England, citing both medical concerns for women and doubts over the dissemination of raised funds. The ban drastically reduced women’s ability to play.

The FA’s political influence over the sport saw regulators the world over stifle the growth of the women’s game through cultural and legislative means. The first Men’s World Cup would be held in 1930, 61 years before women would play theirs.

Some 22 years on from that first edition, women’s football continues to gain pace. It is the biggest growth area for FIFA and the game, with the World Cup just one component of a much bigger plan to capitalise on this. Bareman was tasked with developing a strategic framework for women’s football after being appointed to lead FIFA’s newly established women’s football division in 2016.

“We did a huge amount of analysis on what the current landscape of women’s football is,” Bareman says. “That’s a very extensive piece of work. And based on the outcomes of that research, we were able to develop a strategy, a global strategy. [It was] the first time FIFA was looking at women‘s football with a global lens.”

The document’s scope is vast, with goals set for participation, commercialisation and branding, coaching and referee pathways, governance and leadership, and social impact. It encompasses all levels of the game, and, as Bareman says, “It really is the blueprint that we refer to decide how we prioritise our work, where we put our investments. Everything is driven by that strategy”.

The strategy also spans all 211 of FIFA’s member associations. Globally, women footballers and their allies are fighting similar battles: historic lack of opportunities, patriarchal and male-dominated institutions, entrenched social attitudes and beliefs regarding gender. However, in each confederation, country and region, these battles manifest differently.

“One of the biggest challenges of this role actually is having to deal with such a diverse range of stakeholders,” Bareman says. “And that means we just have to really go in and understand the situation on the ground in each country and tailor-make the support that we provide based on what we find.”

One of Australia and New Zealand’s unique challenges is where football falls on their sporting hierarchies, with other ball sports taking precedence. (Bareman herself grew up in a rugby-mad family.) For local stakeholders, hosting a World Cup presents an opportunity to not only promote the women’s game, but the sport overall. This will be the first Women’s World Cup to feature an overarching legacy framework, encompassing both host nations, their parent federations, and FIFA. It is designed to translate the tournament’s momentum into tangible and trackable outcomes for the future of the game—the next generation of players, referees, coaches, administrators, media and directors.

For while mega-events are often emphatic, and affective, they are also fleeting. It is through the finer details on the ground that, over time, progress is made: progress visible through the fine print of player contracts; the quality of the playing surface; the weave of jersey material; an athlete’s calendar schedule and playing minutes schedule.

As head coach of Sydney FC women’s team, Ante Juric is familiar with these finer details in the Australian football landscape.

Sydney FC is the most successful club in the A-League Women (ALW), the country’s top-division women’s football league. The league’s existence is, in part, the result of the World Cup effect. Australia’s successful run at the 2007 FIFA Women’s World Cup in China garnered attention for the team. It also threw the lack of an elite league for the national team into sharp focus for the game’s stakeholders. In 2008, the then W-League was established.

Juric says improvements on the ground have been substantial since he joined the club in 2017. “There’s a bit more media [coverage]. Facilities are huge because from where it was to where it is, it’s chalk and cheese. You’re training on good grounds. On the weekends, you’re playing on good grounds—mostly. You put all of that together and it’s a huge change.”

The league’s first collective bargaining agreement underpinned much of this progress. It stipulated minimum standards not only for pay, but also facilities, health insurance and maternity support. Such agreements are negotiated by Professional Footballers Australia (PFA), the representative body for semi-pro and professional players in Australia.

Kate Gill has been closely involved with this work, both during her own time as a player and as the current co-chief executive of the PFA. “The ultimate driver in all of this has been the players understanding that they are essentially workers, that they are performing a profession,” Gill says. “[It involves] grappling with that tension of moving from the notion of just being grateful for any kind of crumb of progress that they receive, or anything that comes their way, to deeply understanding that they are professional athletes. They do have rights and protections that they should be afforded.”

This shift in mindset is echoed by Juric, who says that now “the players feel like players”.

The collective bargaining agreement came into effect during a lively era for women’s semiprofessional and professional sport in Australia. Competitive leagues for women have existed for some time, the longest running being the Women’s National Basketball League established in 1981.

However, the past decade has been defined by a rapid rise in semi-professionalism across the board. Codes such as cricket, netball and rugby union have revitalised their premium offerings. The AFLW’s establishment in 2016 was followed by the NRL launching its first national women’s competition in 2018. There have never been so many elite team sports options for women.

The ALW has gone from some players being on $0 contracts—“getting peanuts” as Juric puts it—to a current minimum wage of $20,608. The shift is stark, but there is still far to go. Unlike players in the A-League Men, the ALW does not provide a full-time wage. Players and staff, including head coaches such as Juric, manage football alongside work or study, with training held in the early morning or evenings to accommodate that. “The positive of that is that you can have another job. You can have another life,” Juric says. “The negative of it is girls are sometimes tired, fatigued. I’m sometimes tired, fatigued. For a top professional environment, that’s not the best in the world.”

Many women are expected to adhere to the expectations of professionalism, despite not being provided with the resources to materially do so. This juggle of semi-professionalism is not unique to football—currently only cricket and netball provide full-time wages across their top leagues. Exhaustion from managing the emotional and financial demands of semi-professionalism sees athletes retire prematurely, seeking greener pastures beyond sport.

Recognition of this juggle, even for our top female athletes, helped achieve a landmark pay deal between the men’s and women’s national teams in 2019, when pay parity was established between the Socceroos and Matildas. The men’s players agreed to a pay cut in order for salaries to be made equal. “To actually hear that first-hand account of the sacrifices that the women have made, and the competing demands that they have placed upon them just to be able to piece together a living, [that] was quite confronting for our male players,” Gill says. “There was a great deal of empathy in that conversation as well.”

Now, with national team contracts alone enough to live on, the Matildas work as full-time footballers. But pay parity was as much a cultural win as it was a financial one. It emerged from the recognition that while men’s football has a rich past, women’s football is carving out a spectacular future. “It was that conversation that we had with both our Socceroos and our Matildas about understanding that they are greater than the sum of their parts,” Gill notes of the lead-up to the agreement.

“And yes, the Socceroos for a very long time have been the face of Australian football. But the Matildas’ time was coming. The men who play for the Socceroos understood that they could see the shift and what was happening, and they knew that they needed to support the Matildas in that moment.”

An integral part of these transitional moments involves providing women with the means to advocate for and make decisions for their sport. However, just as they were kept off fields, courts, and pitches, women have been historically excluded from positions of influence within the sporting world’s male-dominated institutions.

“The most challenging thing is around that culture, and the actual dignity and respect that’s embedded within those set-ups that actually allow women the opportunity to grow and develop,” Gill says. “As you know, these are very historic male-run organisations. So it’s changing the zeitgeist in that way as women do have a seat at the table, and they do belong in those institutions.”

Bareman and Gill are exemplars of women who have proven what can be achieved if they are in fact given a position of influence. In Bareman’s case, it was being the sole woman at the table that led to her appointment as chief women’s football officer. In 2015, FIFA needed to remake itself as an organisation following a raft of corruption and fraud scandals. Following her work reinvigorating football in Samoa, Bareman was appointed to the 13-person reform committee to represent the Oceania Football Confederation. She did not know that she was the only woman there until stepping into the room.

“Unfortunately, in my career in football administration ... that wasn’t an unfamiliar situation for me,” she says. “And it’s one of the very reasons actually why, within that committee, one of the most important points that I put forward and continuously drummed in was that we need more women in decision-making positions within our sport.”

Bareman advocated for not only women’s involvement in governance, but for more resourcing and support for the women’s game at large. “I think it was a little bit the fact that I was the only woman in the room,” she notes of the position. “But in saying that, it was not something that anyone could ignore, irrespective of their gender. You know, it was very, very clear even in that room itself that there needed to be more women involved.”

Outcomes of the reform included the formal entrenchment of gender quotas on FIFA’s council and the establishment of a new women’s football division, which Bareman was appointed to lead.

Women’s football’s position as a developing game is the result of a difficult past. Yet in building something new, there are opportunities to learn from the mistakes of the men’s game. Women’s athletes and their allies have, historically, had no choice but to do things differently. Now, the power of women’s sport sits within these points of difference. As Bareman says, “You have to go through a bit of adversity if you‘re involved in our sport and for me that creates resilience and a passion that exists that you can’t find in the men’s game because of the journey people go through to be part of it.”

This resilience and passion is seen with Juric and his Sydney FC squad as they manage the current challenges of semi-professionalism. “We get through it, and we work hard,” he says. “I credit the girls because of that. Because it makes them resilient, stronger than other people who don’t have to go through that in a professional environment. I’ve got nothing but pride for my girls.”

Proud he should be, given Sydney’s recent successes. For three years in a row, the Sky Blues finished at the top of the table. Yet the double—securing both premiership and a grand-final win—eluded them. In the ALW’s finals series, they stumbled at the final hurdle not once, but twice, missing out on the championship to Melbourne Victory both times. Yet the sting of these losses would make Juric and his side more determined in 2023. In April, they emphatically beat expansion side Western United 4-0 in the grand final, playing stylish football. The win made them the most successful team in the league’s 15-year history.

There’s an incredible narrative arc in Sydney’s journey to the double, going off the football alone. The game is different from the men’s, too—physically, technically and tactically. While this difference is leveraged by the unconverted as a reason to not watch women’s football, the outdated sentiment of “women can’t play football” is just that. As Bareman, Gill and Juric all emphasise during our conversations, the game is beautiful, and fun, and fresh.

Yet it’s the stories of the players, the advocates and the communities that lead to what happens on the pitch and elevates women’s football into something even more incredible. Stories of resilience and passion upon which women’s football is built.

This is why the ninth FIFA Women’s World Cup is so important. It is a milestone not just for female athletes and organisers but for everyone. A celebration of how far things have come but also a reminder how much further things are yet to go. It is why the current moment, for women’s football and for women’s sport, is so huge. Not just huge, but enormous, massive. And only getting bigger.

Angela Christian-Wilkes is a PhD candidate researching women’s soccer media makers and co-host of the podcast The Far Post. She dedicates this piece to Mads Horey, a lifetime member of Melbourne University Soccer Club who passed away in May.

The Women’s World Cup runs July 20-August 20.

A version of this story originally appeared in the June/July 2023 issue of GQ Australia, available exclusively in The Australian June 23, with the title “How women’s sport got bigger than ever”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout