How the Ghislaine Maxwell trial left Lucia Osborne-Crowley ‘exhausted and crippled’

When it comes to trauma, the body keeps the score – a lesson Australian author Lucia Osborne-Crowley dealt with during the weeks in New York spent reporting from the frontlines of the Ghislaine Maxwell trial.

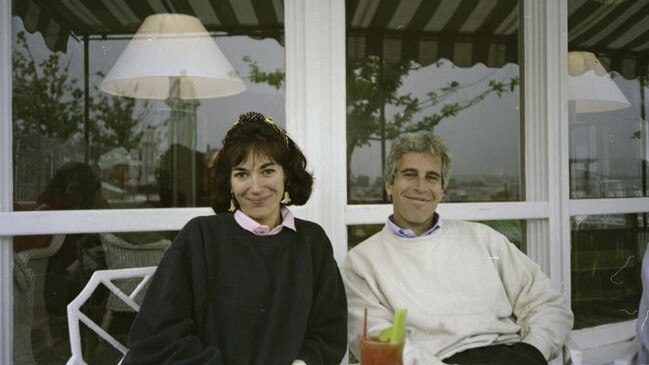

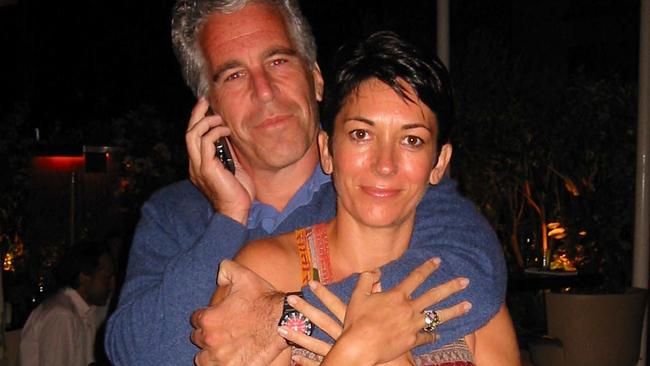

It’s 4am and I’m standing in the frosty air of winter in Manhattan. I have been standing here for two hours. The cold has soaked through my layers of clothes and into my bones. It starts to rain. I am here because I am covering the Ghislaine Maxwell trial – the criminal trial in which Maxwell, the former girlfriend and right-hand woman of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, was found guilty of five out of six charges, including sex trafficking of minor girls.

I am here because for some reason that is entirely beyond me, they only allow four reporters in the actual courtroom each day for the Maxwell trial, and the only way to get one of those four spots is to get in line at 2am. There is no shelter from the rain and no respite from the cold until they let us in the courtroom at around 8am. This cold, this standing up for six hours straight – it’s a marathon to me, as someone with two chronic illnesses.

I have endometriosis and Crohn’s disease, one or possibly both of which – depending on emerging research – are autoimmune conditions. It’s been years since I’ve been able to stand up for this many hours at a time. The pain in my abdomen is searing, my head is pounding from the physical toll this is taking on my immunocompromised body. But I have to stay in line because I think this trial will expose important truths about trauma, the body and memory. It turns out I am right. My many specialists have explained to me that my chronic illnesses are likely the long-term response of my body to my own trauma. I was raped as a teenager and sexually abused as a child, in a situation not too different from that of Ghislaine Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein’s victims. I held on to both of those secrets for a decade, thinking I could outrun them, thinking I could escape these basic biographical facts about my life. But, as I learned later, in the words of psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk: the body keeps the score.

Years and years of my body and my nervous system entering fight-or-flight whenever it was reminded of the abuse I had tried to forget had left me physically exhausted and crippled. So it’s funny to me that the reason I want to be in the room for the Maxwell trial – my quest to better understand trauma in order to contribute to a growing literature around it – is the same reason I can barely cope with the physical pressures of that quest.

Now, my story is far from the most important here. The survivors of Maxwell and Epstein were also made to wait out in the cold, with bodies that were likely crumbling under the intense traumatic response that comes with being in the same room as your own abuser for the first time since you escaped her.

I’m telling you this because I think it speaks to the gap that still exists in our understanding of trauma. We have made strides, absolutely – and putting Maxwell on trial is proof of that. But even in the moments that the powers that be believe they are creating catharsis and closure for the minds and hearts of victims, they are unable to appreciate the effect this has on their bodies.

I have written two books about trauma and the body – I Choose Elena and My Body Keeps Your Secrets – and what I have learned from the hundreds of interview subjects, experts and doctors I spoke to is that we must let go of the idea that trauma is solely an emotional wound if we are to get serious about treating it. The false notion that violence and violation are solely emotional issues is what has kept us from taking it seriously for so long – because, of course, our patriarchal and misogynistic society equates emotion with weakness, and weakness with femininity. And so we disregard the impacts of trauma as something that afflicts the faint-hearted, and we tell ourselves we are stronger than the people who suffer lasting effects of traumatic events.

I know, because that’s what I did for 10 years. After my rape at knifepoint on a night out in Sydney, I truly believed that allowing myself to be impacted by it would represent some fundamental failure of character, of tenacity. So I ignored it, and I ignored all the signs that my body was in turmoil. I ignored it until it landed me in hospital years later – and even then I tried to tell myself that my personal fortitude could save me from the effects of violence. But it doesn’t work like that. The truth is that the brain and the body register the imprint of fear in a way that cognitive thought cannot overcome. And that over time, a chronic fear response, a chronic re-entry into fight-or-flight several times a day, whenever a fragment of a traumatic memory flies out at us, breaks the immune system down until it can no longer function properly. It causes a chronic inflammatory response all throughout our bodies as we try to fight off a danger we have already survived but which has been indelibly implanted on the body.

“What I have learned from the hundreds of interview subjects, experts and doctors I spoke to is that we must let go of the idea that trauma is solely an emotional wound if we are to get serious about treating it.”

A 2015 study found that traumatic experiences in childhood are a reliable predictor of poor health in adulthood, including diabetes and heart attacks. Another 2020 study confirmed that adverse experiences in a person’s young life directly correlate with lifelong stress-related physical health conditions. Another study shows that those with post-traumatic stress disorder are much more likely to develop heart disease, cancer, bone fractures, chronic lung or liver diseases, diabetes and stroke. The list goes on. But there’s another way that trauma affects the body, too – something I explore in more depth in my second book, My Body Keeps Your Secrets. Very often, the physical symptoms of a traumatic stress response – including increased heart rate, skyrocketing blood pressure, tunnel vision, profuse sweating – can be so anxiety-inducing that we are forced to find ways to numb those physical symptoms. Numbing responses include alcohol, drugs, overwork or obsessive busyness, perfectionism, and many other kinds of escape. These are not weaknesses or failures, as society would have us believe, but rational responses to physical sensations that are overwhelming and frightening.

I want to tell you a story about a woman named Carolyn. Carolyn was abused by Jeffrey Epstein, with the help of Ghislaine Maxwell, between the ages of 14 and 18. She was forced to give Epstein massages that turned into sexual abuse for four years – until he started asking her to bring younger friends around instead. When Carolyn took the stand in the trial, she told the court that she started taking pain pills and other drugs during this time in order to “block out the appointments” with Epstein. She felt sick afterwards, she said, and the drugs helped her cope with that physical sensation. This later turned to a heroin addiction, which she suffered with for much of her adult life.

When we heard from her in court, she was on a course of methadone to help her come off the drug. Carolyn’s speech was slurred as the defence attacked her and accused her of not being credible because of her drug habit. They told the jury in closing arguments that they should not trust the story of a woman who abuses drugs. But sitting in that courtroom, I knew something that those defence lawyers did not, or did not want to admit – Carolyn’s use of drugs does not undermine her story of sexual abuse; it is proof of it.

The same is true of a woman named Kate, a pseudonym. When Kate took the witness stand to describe her abuse at the hands of Maxwell and Epstein, again the defence attacked her over the drug addiction she developed during and after the abuse. When Kate recovered from her drug addiction later in adulthood, she set up a foundation to help traumatised women who struggle with substance abuse. Both of these women were repeatedly sexually abused as teenagers but felt unable to speak of it to anyone. The shame and fear was overwhelming. So was the physical feeling they had after every encounter with Jeffrey Epstein. So that trauma showed up on their bodies when it couldn’t be processed by their minds or spoken aloud. The body keeps the score.

On one of the days of the trial, my abdominal pain became truly unbearable. All those hours of standing in the cold followed by many more hours of sitting on hard wooden benches in the press gallery had become too much. The inflammatory process that was taking over my body then spread into my feet – something that has happened only once before. When I stood up to go to the bathroom, I found myself with a severe limp. The witness who was on the stand that day was an important one, and I didn’t want to miss anything. For a while, I forced myself to sit there. But then I realised that pushing myself to breaking point in my desire to outrun myself is the thing that caused my illness in the first place. I realised I had to leave; had to go back to my hotel room and take painkillers and lie in darkness until my body recovered. And that’s what I did.

I was finally able to act on the lesson I have spent years trying to learn – that although I can learn a great deal about trauma by reporting on events like the Maxwell trial, I can learn infinitely more about it by listening to my body when it speaks, and by honouring its need for rest. By abandoning my destructive tradition of forcing my mind to override my body in a bid to outrun its limits. By putting my body first. By finally heeding its score.

Maxwell is appealing her convictions.

Lucia Osborne-Crowley is the author of I Choose Elena (Allen & Unwin, $16.99) and My Body Keeps Your Secrets (Allen & Unwin, $29.99).

This article appears in the March issue of Vogue Australia, on sale now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout