How Australia’s fledgling ballet company proved its worth

A decision made sixty years ago has had a lasting legacy on the Australian Ballet company.

Few ballets occupy our collective cultural consciousness in quite the same way as Swan Lake.

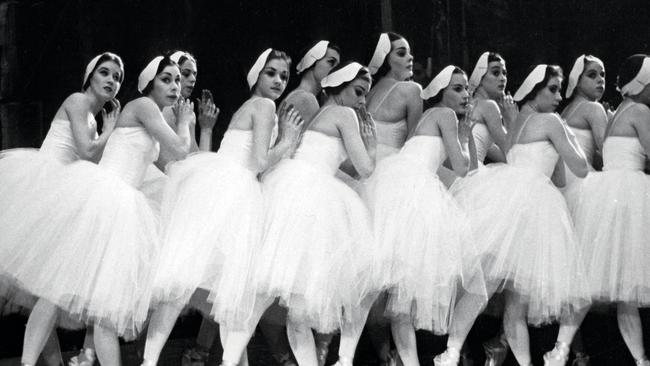

Those haunting opening bars of Tchaikovsky’s heart-rending melody; the melancholic theme introduced first by the oboe, before being adopted by the rich, sonorous drone of the cellos. The pas de quatres of the cygnets; holding crisscrossed hands, the light patter of the dancers’ pointe shoes as they relevé passé, possibly as distinctive as the music itself.

It was the perfect choice to herald the first season of the brand-new Australian Ballet company – an indisputable classic, beloved by all, and unparalleled in its romance, spectacle, and technical difficulty.

Swan Lake opened at the now-defunct Her Majesty’s Theatre, Sydney, on November 2, 1962. Sitting in the audience that night was Lady Primrose Potter AC, CMRI, a true ballet lover and benefactor of the arts. On the stage that evening in the corps de ballet was 27-year-old Colin Peasley, OAM, who today holds the record as the longest-serving member of The Australian Ballet and who fittingly ended his career, at age 78, with one last performance of Swan Lake. Five nights later, Marilyn Jones, OBE, also took to the stage as the third prima ballerina to perform Swan Lake for the season.

Throughout the 1940s, Australia experienced its first real taste of a premier ballet company, in the form of the Borovansky Ballet, created and led by dancer, choreographer and director Edouard Borovansky. However, only so much could be achieved without sufficient funding and support – and ultimately, it was Borovansky’s sudden death in 1959 that proved to be the catalyst for the formation of our first cohesive national ballet company, one that would be necessarily subsidised by the government and bolstered through a partnership between J.C. Williamson Theatres and the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust.

Their first order of business was to appoint the formidable, widely respected ballet grande dame Peggy van Praagh as artistic director, who toured Europe over the course of her illustrious career, and counted among her pupils one of the most famous ballet dancers of all time, Rudolf Nureyev. According to Jones, the question regarding the creation of a national company was never if, but when.

“Peggy always believed that The Australian Ballet would start,” Jones explains. “I always said, ‘Yes, I would come back, of course, to Australia.’”

So it was that van Praagh assembled her dream company, hand-picking the most talented Australian dancers, now scattered across the globe.

“People came out of the woodwork everywhere to get into this company,” says Colin Peasley, who successfully auditioned for van Praagh, and had been itching for an opportunity like this. “It’s what I wanted to do!”

It was decided Swan Lake would be the production to introduce Australia to its first national ballet company. As well as comprising all the essential elements – drama, passion, deception, love and immense beauty – it’s also a means for a fledgling company to prove its worth on the world stage.

Hallowed as one of the most technically difficult roles, Swan Lake’s principal ballerina must not only depict Odette (a princess trapped in the body of a swan), but also her converse, the duplicitous Odile, whose aim is to trick the prince and prevent him from breaking Odette’s curse. So when Jones was selected as one of three female principal dancers who would tackle the complex dual role, she was both excited – and anxious.

“Not only the dancers were excited by that first performance, the entire audience was excited”

“Swan Lake and Sleeping Beauty are the two things that most dancers aspire to,” says Jones, who was just 22 at the time. “And they still are today. Technique has improved enormously, but those roles are still nerve-wracking. One minute you’re just a lovely, innocent swan who falls in love. Then next, you’re pretending to be her, but quite evil,” Jones adds to Vogue. “It’s a great role!”

In addition to Jones and her partner, Swedish dancer Caj Selling, and fellow company members Kathleen Gorham and Garth Welch, international stars Sonia Arova and Erik Bruhn were imported to perform the principal roles on alternating days.

“They were [among] the greatest dancers in the world,” Peasley enthuses. “When we went off stage after our performance, we’d all linger in the wings, checking out what they were going to do in the next half. They taught us more than what we’d learned in class.”

On a grey day in early September, the 44 dancers comprising the brand-new Australian Ballet company met for the first time as a cohort at their studios in Melbourne. They had just over eight weeks until opening night in Sydney. For between eight and 12 hours each day, they rehearsed under the tutelage of van Praagh, as well as teachers Ray Powell and Leon Kellaway.

“In those days we didn’t have much time to rehearse, you learned the ballet pretty fast,” Jones says. “It didn’t faze me too much, but you always get really nervous, of course, [especially] when it’s the first production. You get butterflies. Sometimes, you want to run in the opposite direction. There are so many things that could go wrong, like the 32 fouettés.”

Jones’s nerves were entirely justifiable; those infamous consecutive pirouettes are the most that any ballet – past or present – demands of a dancer. Musical Director Noel Smith and his orchestra were hard at work, familiarising themselves with the nuances of Tchaikovsky’s evocative score. In Melbourne, set designers painted immense flats with ornate scenes of palace interiors and of course, the mystical lake. In the wardrobe department, frothy tulle, reams of silk and diamantés covered every surface, gradually taking their final forms as tutus and tiaras.

“I think it was [Margot] Fonteyn’s pattern that they used,” Jones recalls. “So the costumes were really nice. We had feathers and feathers!”

In Sydney, backstage at Her Majesty’s Theatre, the dancers practised their pre-performance rituals – applying makeup, warming up their pointe shoes, stretching lithe limbs at the barre. In the audience, among the genteel red velvet and gold brocade of the theatre, sat Lady Primrose Potter, listening as the orchestra members practised arpeggios and tuned their instruments. Glamour was in the air.

“Everyone had on fabulous furs and jewellery,” Potter reminisces. “It wasn’t like it is now when someone might have a singlet on! It was wonderful. Then the lights dim and the drums roll and you know it’s off.”

Hours later, as the performers took their bows – exhausted but exalted – to rapturous applause, it became clear that a new chapter in Australia’s cultural landscape was beginning.

“Not only the dancers were excited by that first performance, the entire audience was excited,” Peasley says. “There was a buzz, believe me! We had full houses every night.”

Lady Potter adds that the company was instantly received “with open arms – everyone was thrilled to bits”.

Today, Swan Lake has been performed in full by The Australian Ballet a number of times, and will also feature as the crowning jewel and opening production of their 2023 season – a poignant choice to celebrate and honour the company’s heritage.

Six decades may have now passed, but Jones says she still remembers feeling, as the curtain fell that day at Her Majesty’s Theatre, that something truly special had just occurred – “I knew it was part of history.”

The Australian Ballet’s 60th anniversary season, which will include a new interpretation of Swan Lake, opens in March 2023.

This article appears in the November issue of Vogue Australia.