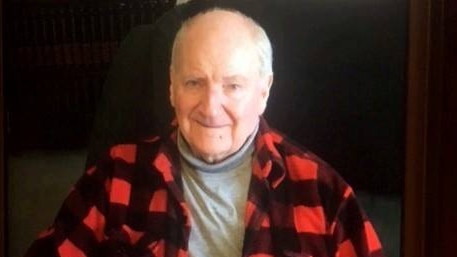

‘He waited for help that never arrived’: the tragic end of Bernard Gore

Tragic final hours of man who died after becoming trapped for weeks in a Westfield shopping centre stairwell finally.

Death by misadventure. It makes it sound like Bernard Gore, 71, died while doing something foolhardy, or somehow daring. Jumping out of a plane with a poorly tended parachute. White-water rafting without a helmet on.

In fact, this gentle, loving father of three, this retired bread delivery driver who still worked as a freelance barber for his friends in Hobart, died in a state of acute anxiety and confusion at Westfield Bondi Junction in Sydney.

He had gone there to meet his wife, for lunch. He had a touch of dementia, and opened a fire door, and stepped inside a stairwell, and when the door shut behind him, he couldn’t get out.

His family reported him missing the same day.

NSW police were put on the case, as were security guards working at Westfield. And yet it would be three weeks before Gore’s body would be located, in a kneeling position on the floor in the stairwell. It seems that he had found a chair to sit on while waiting for help. At some point over the next 21 days, he’d toppled over.

Why did it take police so long to find him? Because nobody — not police, and not security — searched the stairwell. Nobody opened any of the fire doors, and nobody went up and down the stairwell to try to find him, and you’re probably thinking well, why the hell not? Because that’s a pretty basic thing for police and security to do, isn’t it?

An elderly man with a cognitive impairment goes missing at a major shopping centre — why wouldn’t somebody open the damn fire doors and look in the stairwells? Because who hasn’t at one point or another opened a fire door and found themselves trapped on the other side?

It’s an easy thing to do.

NSW deputy state coroner Derek Lee has for 12 months been trying to find answers to those questions for Gore’s family. In delivering his findings on Friday, he sketched a portrait of a man who until his death lived a modest and quite wonderful Australian life.

Bernard and his wife Angela were married for more than 50 years. They lived in Mornington, Tasmania, in the same house they had purchased as newlyweds in 1968. They had three children: Mark, who lived in Tasmania, and Melinda and Rachel, who had moved to Sydney for work.

Bernard and Angela would often travel to Sydney to see their daughters at least once, and often three times a year. They mainly stayed with Melinda, who lived in Woollahra, about 20 minutes’ walk from the Westfield near the train station at Bondi Junction.

Their last visit, in 2016, came just a few months after Bernard began experiencing some signs of cognitive impairment. He’d gone shopping with Angela in Hobart, and become lost. Police had to bring him home.

Angela took him to see their GP, who put him on medication, and Angela made sure that Bernard started taking it.

It made a difference. On December 5, 2016, his score on a cognitive test had improved. Then on December 16 — four years ago this week — they travelled to Sydney for Christmas.

Bernard was a terrific house guest, easily able to entertain himself. He went walking most days, often by himself, for between one and three hours.

He liked to watch the pianist at Westfield play Christmas songs. He really liked the soft-serve ice-cream from the McDonald’s in the food court.

On January 6, 2017, he woke between 6am and 7am, and had toast for breakfast. It was raining so he watched some TV. Around midday he announced his intention to walk to Westfield, and Angela said she’d meet him near Woolworths at around 1.15pm.

He wasn’t wearing his GPS watch because it wasn’t working. He did have a note in his pocket, with his name and a contact number on it. And so, off he trotted, with Angela not far behind, but then, when she arrived at the appointed place at the appointed time, there was no Bernard.

She looked around for a while, before heading back to Melinda’s apartment, and there was still no Bernard. They waited and fretted and then, as it began to grow dark, around 8pm, they called NSW Police, telling them that Bernard had set off for Westfield eight hours earlier and they hadn’t been able to find him.

Police opened a file, and made inquiries, but Bernard wouldn’t, in the end, be found for three weeks.

At 8am on January 27 — the day after Australia Day — a maintenance worker opened door L407 to investigate a report of a bad smell. He walked to the bottom of the stairwell and found Bernard “lying in a semi-kneeling position on the ground with no signs of life”.

“It appeared that Bernard had been sitting on a chair that was found near his body and that at some point he had fallen forward and off the chair,” Magistrate Lee said.

His death had not been immediate. “He was found at the bottom of the stairwell from door L407, three flights of stairs from where he entered and in an alcove under the last flight of stairs,” Lee said.

“Bernard had removed some items of clothing: his hat, shirt, skivvy and T-shirt. A number of personal items were found on the ground near Bernard’s body: a handkerchief wrapped around a set of upper and lower dentures, and a man’s wristwatch.”

An investigation by police revealed that there had been a way out of the stairwell for Bernard: a door down several flights of stairs and at the end of a long corridor opened onto a paved courtyard on Oxford Street.

There were red arrows on the walls and illuminated green EXIT signs, but it seems that Bernard never found the right path to safety. The court heard this may have been because even mild dementia “can cause unpredictable behaviour which can in turn be heightened by stress, anxiety, confusion, hunger, thirst … it’s possible that these matters prevented Bernard from being able to self-rescue once inside the stairwell”.

His only hope was that somebody would find him. So why didn’t anyone open the doors and look? Lee says this was because NSW Police “formed the view that Bernard never arrived at Westfield … They assumed that security had reviewed the CCTV footage of all entrances … They assumed security were searching or had performed a search of Westfield in the same manner as police might conduct such a search.”

Security, meanwhile, weren’t searching the stairwells or much of the CCTV because they had “no confirmation that Bernard had made it to Westfield” on the day of his disappearance, in part because the first call from police to security was to ascertain whether Bernard had been seen there.

The coroner’s court heard that more than 20 million people pass through Westfield every year, and security had never before had a missing person they couldn’t find. Normally it is children that go missing and most are reunited with their parents within 10 minutes. There was a “white level” search involving all stairwells, loading bays, docks and carparks that they could have conducted, but it was reserved for bomb threats and other terrorist activity.

It has now been extended to cases such as this.

The court heard that security guards were meant to check the fire stairs at least once a month, to make sure they weren’t blocked or filled with drug paraphernalia, and such a search was done on January 19 — two weeks after Bernard went missing — but the alcove in which he’d taken his seat was missed. Security checks are now being done more frequently, and thoroughly.

Lee concluded that the “stressors” that Bernard would have experienced in the stair well — both psychological and physiological — were “possible significant contributors to his death”.

Taking this, and the “identified shortcomings” and “inadequacies” of the search into account, he concluded that “it cannot be said that Bernard’s death was entirely due to natural causes. It seems more appropriate to conclude that the manner of Bernard’s death was the result of misadventure.”

Lee acknowledged the strain on Bernard’s family as they tried to come to terms with what had happened. If only this. If only that. If only we could go back in time, to have a young police officer open the fire door to find Bernard sitting there; to have him say something like, well, hello, are you lost? And to lead this nice man to safety.

It’s not possible.

“But inquests are as much about life as they are about death,” Lee said. “The inquest exists because we recognise the fragility of human life.”

Bernard had no choice in his confusion to wait for help that did not come.

“The distress that Bernard must have felt, and the uncertainty and anguish of his family, is unimaginable,” he said.

“But I hope … the lessons learned will mitigate the possibility of another family having to endure such a traumatic event.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout