Google’s plan to play Big Brother in your home

Google wants to extend its electronic surveillance of people’s lifestyles.

Home automation is sailing into uncharted waters. Google has obtained a patent covering using audio and infra-red sensors and cameras in homes to observe the actions of families and help them conform to “policies”. Google also wants to patent using a camera to work out the title of the book you are reading in bed.

Rather than being about clever technology, it seems a case of Big Brother having arrived. George Orwell would be gyrating in his grave if he knew what the patent authors had in mind. The tech giant already is under fire over its electronic surveillance of people’s location and activities on smartphones, as well as its use of organisations’ intellectual property.

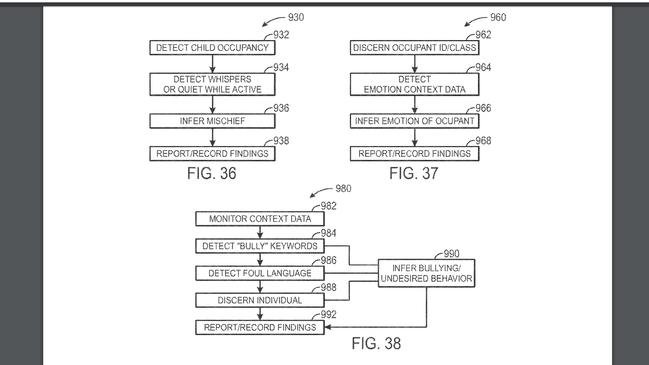

It may be useful to know if your kids are taking illegal substances, but would you need a report into whether they are whispering or keeping quiet? Are you comfortable about technology monitoring your every move?

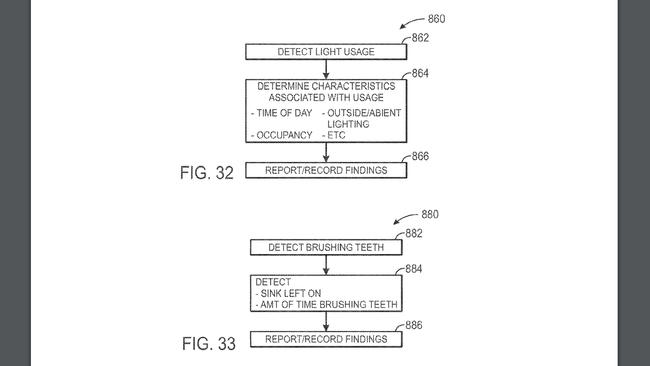

Those behind the patent see the future household as governed by family rules or policies. Sensor technology increasingly can work out where people are and what they are doing, with the aid of artificial intelligence. In this case, a smart home system monitors householders’ observance of rules and reports back findings.

Policies might place limits on water and energy use, on children’s television use and time online, but they could be specific, such as how long children brush their teeth and whether, as the patent mentions, they turn off the basin tap afterwards. Could Google report back that you forgot to replace the cap on the toothpaste?

There’s reporting around the pantry, fridge and dining room, so eating habits appear to be in Google’s purview, as is whether your kids are quiet, whisper, utter foul language or get up to mischief. But would you want technology to watch your family’s every move at home and have it jotted down in a report?

The other question is how much of this behaviour would make it into the public domain, given that the home is shaping as a huge marketing battleground between Google, Amazon and others worth billions of dollars.

The use of sensors and cameras coupled with artificial intelligence means more data about people’s likes and habits.

Patent US10423135B2, dated September 24, is headed “smart-home automation system that suggests or automatically implements selected household policies based on sensed observations”.

Under the plan, sensors, including Nest cameras, infra-red detectors and audio monitors, could be placed in bedrooms and bathrooms as well as living rooms, kitchens and home office space.

You might specify a policy of your children not watching more than one hour of TV at night. Cameras and infra-red sensors aided by AI could observe which children are watching TV in the living room and for how long, and enforce the one-hour viewing limit. Monitoring devices could ensure that children are not watching adult material classified outside their age range.

Again, would you trust Google not to squirrel away the sensor data of children’s programming likes, dislikes and viewing habits for marketers targeting kids and their parents?

Charities, government, academic institutions, utilities and businesses are linked to the system in one Google flowchart.

In the patent, policies are held by a “household policy manager”. One diagram talks about systems suggesting as well as carrying out available policies. A “demographic survey” stipulates the number, age and sex of adults, the number of children, as well as dogs and cats.

The patent says one policy might be to keep the front door locked “when Sydney is home alone”. “If you added one additional audio sensor to bedroom two, sensor confidence regarding when Sydney is home alone will improve by 72 per cent,” one diagram says. “If you moved sensor from bathroom one to bedroom three, sensor confidence would improve from 63 per cent to 98 per cent.”

Other scenarios include detecting running water in the sink, shower or toilet in the bathroom, detecting child behaviour at home and online, emotions of occupants, “mischief”, and “bully” keywords online.

Detection of volatile organic substances, inferring “interaction with undesirable substances” (drug taking), reporting unfinished chores, gleaning data associated with medical conditions, detecting the “interaction between babysitter and kids” and punctuality are other cited examples of observed and reported activities.

The patent argues that this monitoring will make better use of available household devices. “As society advances, households within the society may become increasingly diverse, having varied household norms, procedures and rules.

Unfortunately, because so-called smart devices have traditionally been designed with predetermined tasks and/or functionalities, comparatively few advances have been made regarding using these devices in diverse or revolving households or in the context of diverse or revolving household norms, procedures and rules.”

The patent lists an array of sensors and cameras that can be used to monitor home activity. They include cameras and other optical sensors, microphones, temperature sensors, humidity sensors, accelerometers, active or passive radiation sensors, GPS receivers, hazard-related sensors and other environmental sensors.

These sensors would detect acceleration, temperature, humidity, water, supplied power, proximity, external motion, device motion, sound signals, ultrasound signals, light signals, fire, smoke, carbon monoxide, GPS signals, radio-frequency (RF) signals, other electromagnetic signals or fields, visual features, textures, optical character recognition (OCR) signals, and the like.

Newer devices such as Google Nest Hub Max use facial recognition and they can track you around a room to keep you in view.

A Google spokesperson says patents don’t necessarily reflect the company’s product plans. "We file patents regularly and they aren't necessarily reflective of our product plans, and may never be used in products at all.

“We always strive to be thoughtful when introducing new technologies to the home which is why we published a guide to explain as clearly and simply as possible, how our connected home devices and services work, and how we uphold our commitment to respect your privacy."

But Sacha Molitorisz, a research fellow at the University of Technology Sydney’s Centre for Media Transition says Google’s idea throws up lots of issues.

Children cannot give meaningful consent to being monitored. “Collecting that sort of data about adults is quite revealing, collecting data about children is even more revealing and worrisome because they’re vulnerable. This data is very, very valuable.”

He is worried about the cumulative effect of collecting and matching information. While monitoring a family’s eating habits in a dining room, microphones might detect a couple arguing. Video would confirm a domestic dispute. Over time you could profile a couple.

“Various bits of data can be put together with other bit of data, so that very accurate profiles of individuals can be collated. Once you start getting the emotional data and the real workings of the household, it is concerningly detailed. I think we need to have a long, hard think about this sort of tech.”

He says Google and Amazon have put effort into recognising the emotional state of people.

He has reservations about cameras in bedrooms “while I imagine a number of other people might not”.

He says Australians are not adequately protected by privacy law. Society had to develop a legal and ethical framework to ensure “we’re not just implementing tech because we can”.

Not everything Google does with artificial intelligence is necessarily bad. The Australian this week reported on Project Euphoria, where technology helps people with speech impairments to communicate more easily.

The report says Google project manager Julie Cattiau is working on taking underwater data from whale species and liaising with shipping companies to avoid collisions with marine life, such as humpback whales. It’s part of Google’s AI for social good program, which includes great initiatives on physical and mental health, and generous grants to start-ups and the community.

However, that generosity is aided by profits that Google obtains by using intellectual property that belongs to others, such as news snippets. Google hasn’t shown the same generosity when asked to pay European publishers for the right to show their content on Google News. Last month it refused a request from French publishers for this point blank.

Last month Google suffered yet another legal defeat at the hands of US tech giant Oracle, which has been pursuing Google in the courts for a decade for using 11,500 lines of computer code that Oracle says belongs to it. The problem is the code is part of the early Android operating system.

Google did chalk up an early legal victory but in recent times the courts have ruled consistently in favour of Oracle, which reportedly is seeking about $US9bn ($13.3bn) from Google.

There’s Google’s inability to answer questions raised by this paper in July on so-called shadow profiles. We reported that Android phones were sending a constant stream of personal data to Google independently of what was collected publicly by apps.

The data includes locations scans, barometric readings, changes in the rate of data accumulation and activity scans, and details of nearby Wi-Fi access points. When offered an opportunity to explain what is happening, Google offered no direct answer.

Further, on the phones being tested, it was hard to find any evidence of the barometric pressure readings, change in the rate of data use and Wi-Fi scan information being available to the user, nor it being available in the Google “download your data” service. However, this information, when matched with the time-stamping, can indicate a person’s pattern of life.

This new patent is not the first time Google or rival Amazon has looked at extending the functionality of home digital assistants. In 2014, Amazon patented an algorithm that would let it capture voice content near an Amazon device. It wanted to listen to conversations for keywords that could show a user’s interest in targeted advertising and receptiveness to product recommendations. The application wasn’t just about processing commands sent to Alexa.

Google previously filed information that’s similar to this 2019 patent in an early application in March 2015.

In one patent application, it talks about using a video camera to determine what you read in bed.

“A sensing device, such as the smart video camera, may use its sensor and processor to perform object recognition, pattern recognition, optical character recognition (OCR), and the like,” the application says. “For example, the smart video camera may use OCR to ascertain that the book on the user’s bedside table is titled The Godfather.”

The application talks about sending an electronic version of the book to your tablet or phone, but there’s nothing to stop knowledge of your bedside reading habits being used for other commercial purposes.

Home automation has the potential to relieve us of some tedium we face in everyday life, but there needs to be a clear line drawn in the sand. Our privacy is at stake. How much of your intimate home life are you prepared to share with advertisers?

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout