Windows Hello: can identical twins fool Microsoft and Intel?

Windows 10 includes facial recognition software supposed to render passwords redundant, but does it work for everyone?

Windows 10, released last month by Microsoft, replaces the hackable password system with biometric recognition. You log in using your fingerprints, and with eye and face recognition.

The new feature is called Windows Hello. If you have an iPhone or recent Samsung smartphone, you will know how convenient fingerprint recognition is, and it has proved consistent and reliable.

But a large number of notebooks coming on to the market with Windows 10 offer face recognition as an alternative to passwords for accessing your account.

The face recognition process involves a RealSense camera made by Intel, which sits embedded above the display. Three cameras — featuring an infra-red lens, a regular lens and a 3-D lens — use photographic analysis, heat detection and depth detection to decide who is at your computer display.

Personally I found face recognition worked a treat. The Lenovo Thinkpad Yoga 14 we used quickly identified who I was among several account holders, and in a flash logged me in.

Before you could say “Satya Nadella”, I was transported to the Windows desktop.

In fact, it worked too well. On a few occasions after I logged out, the laptop’s camera noticed I was lingering at the display and quickly logged me in again.

But would it work with identical twins? Could the Lenovo distinguish between the two, or would the camera let the second twin log into an account registered with their sibling’s face?

Could we possibly derail Windows Hello?

We approached the Australian Twin Registry to find siblings who might be prepared to collaborate in our experiment.

About 40,000 pairs of Australian twins are on the registry and make themselves available for health and medical research. We thought that a little digital research wouldn’t be a stretch.

If Hello were to fail the twins test, it would be a huge blow for Microsoft. One in 40 people is a twin, says ATR director John Hopper, and one-quarter to one-third of the pairs are identical. That’s 1 per cent of the population.

Twins are, however, a diverse bunch, Hopper says. Some are so close that as adults they live together rather than marry. Some are great friends but highly competitive. Still others regret the existence of their identical sibling.

Hopper recalls a letter from a twin imploring the registry to end its correspondence “because when I get a letter from you, it reminds me of her”. Whatever the case, everyone is entitled to privacy.

We worked with six sets of identical twins in Melbourne and Sydney. In each case, the procedure was the same. One twin would register a Windows account on the Lenovo Thinkpad and go through the face registration process. Users could enhance the camera’s accuracy by registering variations in appearance, such as wearing glasses.

The first twin would make sure the computer reliably identified them before the moment of truth arrived. Could the second twin trick the camera?

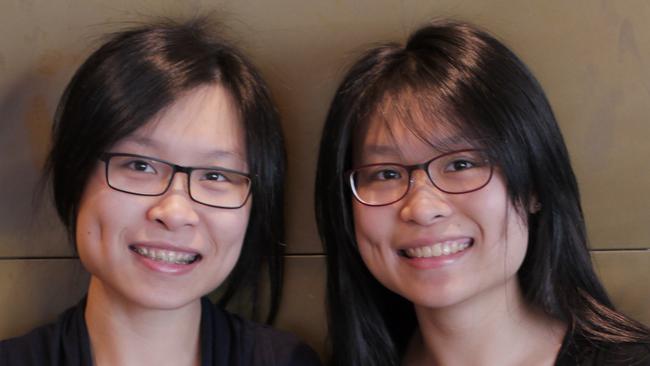

Annabelle and Miriam Jeffrey were among those who failed to fool the technology. “It could distinguish between us two quite easily,” Miriam Jeffrey says. “It’s a little surprising, I thought it would have failed, but no, it was really good, it was really quick.”

But there’s a chance for togetherness, should twins want it. The Jeffreys later registered a Windows account using both their faces, whereafter both were able to use the same face recognition login.

Other twins tried fooling the camera by removing their glasses or rearranging their hair.

Sharon Tay initially could not get facial recognition to work but eventually succeeded. Her sister Nicole couldn’t log in at all. They were philosophical about the test. “The thing is we know each other’s passwords for a lot of things. There’s no point,” Nicole Tay says.

In the case of George and Henry Blood, 13, the computer correctly logged in Henry but not his brother. It eventually identified our youngest twins, Abby and Libby Sukkel, 8, and instantly distinguished between teenagers Issie and Tash Secanski.

In the case of Isabelle and Natalie Brown, 11, Windows Hello was unable to log in either. That was the only instance where the system failed. In the end, there were some cases of Windows Hello taking its time to identify a twin, but no case of it wrongly granting access. That’s a win for Intel and Microsoft.

Windows Hello is the entree to a wider service called Microsoft Passport. Once you are authenticated by Windows Hello, Microsoft Passport can securely log you into other programs or websites. That includes not only various Microsoft programs but also other programs that support a protocol called Fast ID Online.

All this is designed to entirely supersede, eventually, the password system, which is universally regarded as broken.

Apart from Microsoft, the FIDO Alliance seeking to bring about a uniform system of online authentication includes heavy hitters such as Google, Lenovo, Mastercard, Visa, PayPal, Samsung, Synaptics and chipmaker Qualcomm. They are all on the alliance’s board.

Microsoft says Windows Hello is based on “asymmetric key cryptography”, technology that powers smart cards and is used to verify web servers and mobile phone networks.

It’s well established but previously hasn’t been adapted to consumer computing.

Microsoft says hackers cannot steal your biometric information. The heat-sensing IR camera doesn’t allow access to someone waving a photograph in front of the camera. The IR camera also increases reliability in cases where users wear cosmetics, have facial hair or there’s a variation in lighting conditions.

According to Microsoft, the biometric key is stored only on the device where facial recognition is established, and usable only with it. So a hacker would need to steal your computer to even attempt authentication.

Microsoft claims a false acceptance rate of lower than one in 100,000. It says the incident whereby a Russian hacker last year posted 1.2 billion passwords on the net shows passwords are a lost cause as a security measure.

To join the Australian Twin Registry, freecall 1800 037 021 or visit twins.org.au.

Video journalists James Tindale and Eric George conducted and filmed twins using Windows Hello in Sydney and Melbourne.