Sony PlayStation VR headset is a virtual reality bite

The terrifyingly real PlayStation VR headset will change the way we play computer games.

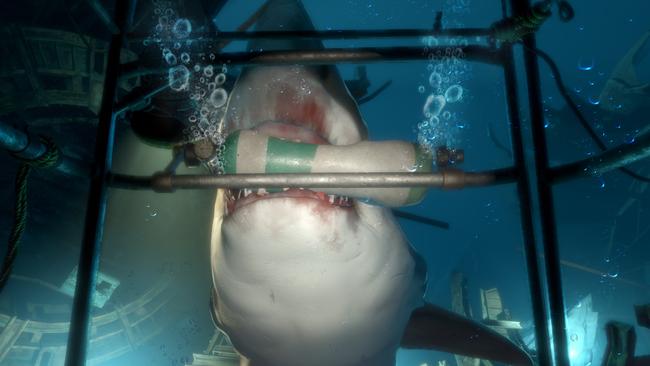

The killer shark with pearly-white choppers circled the small diving cage in which I was trapped. It wasn’t fun.

After several passes, the shark morphed from casual stalker to frenzied attacker, cutting off my air supply in one strike and progressively chomping off sections of the diving cage, leaving me exposed to that fatal, rabid attack.

I’ve a history amid sharks before, but not quite like this. In 2004 my old paper sent me to write up an extreme sports weekend. I went frolicking with the seals and swimming in a tank of sharks at UnderWater World on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast. It was tame stuff; thousands do it. The sharks are amply fed, although you always worry that one may have a brain snap. But it was a real experience.

Two decades earlier, on a night-time scuba dive off the Queensland coast, someone called out that they spotted a shark. From a long distance out on a dark night, we linked hands and calmly swam to the beach. It took an eternity.

That was real too. But my experience in that diving cage wasn’t real. It was a virtual reality experience courtesy of Sony’s VR headset for PlayStation 4. But what really puzzled me was the reaction of my body to that virtual reality shark: surging fear.

As the shark kept approaching, I felt the surge of a huge adrenalin rush. My body wanted to leave in a hurry despite my brain continually saying, “this isn’t real”. I felt incredible agitation but I stood my ground — for a while at least. I am not a dedicated gamer seeking an adrenalin high; this was involuntary, huge and painful. I felt in real danger. When I returned to the office, I was exhausted.

It makes me think the new era of super-real virtual reality, which is set to change the way we play computer games, isn’t for the faint-hearted. And that era is upon us — Sony’s VR headset for PlayStation 4 was demonstrated at the Paris Game Show this week. It’s the first VR viewer by a big gaming company and heralds gaming as a VR experience. But it makes me wonder: just how safe is this?

The headset will be released in global markets including Australia next year. Its price has not been revealed. As technology journalists invariably do, I had a chance to preview the PlayStation VR a few weeks back.

Actually, the shark and the general environment contained in the game The Deep isn’t entirely realistic, but your view into the world of VR is sharp and crisp: 1080p full high-definition resolution on a 5.7 inch OLED display. With headphones, I was totally closed off from the physical world.

And I could walk around that virtual world. I could physically turn and move a couple of steps on that narrow, confined platform. My body’s movement, I believe, was enough to trigger its physiological responses.

In the real world, you’ll need an open area with no obstacles, no split levels or stairs so you can walk around and not trip over while you use the PS VR. It’s a good idea to play with another person present in the room. You have the option to output your vision to a TV to share what you’re seeing.

PlayStation VR is the new, simple name for what was Sony’s Project Morpheus in its development stage. Morpheus is the Ancient Greek god of dreams, and to me the perfect name for a VR system. But simplicity ruled and Sony announced the name update to PS VR at the Tokyo Game Show last month.

Now I sit next to a bank robber driving a getaway car along a London freeway. Marauding bikies pursue us, firing round after round. For this revised version of the game The London Heist, I used PlayStation Move Controllers that the headset picked up as my hands. I could open the glove box, take out a gun, load it with magazine rounds and fight off the bikies while sitting next to the driver.

On-screen killings put to one side, people have died from playing regular computer games. They are mainly people playing for incredibly long periods, such as a 40-hour session of Diablo III that led to a blood clot in the leg from inactivity, or 50 hours of StarCraft that ended with heart failure caused by exhaustion and dehydration.

But there are cases of moderate gamers dying after a large adrenalin rush, such as the reported death in 2013 of 16-year-old British teenager Jake Gallagher who suffered from Asperger’s syndrome and had an undiagnosed heart condition. He had a heart attack playing Sonic the Hedgehog.

When I relate my virtual shark encounter to Michael Ephraim, managing director at Sony Computer Entertainment ANZ, he reveals his wife had the same experience playing The Deep.

“The adrenalin was running through her to the point that she almost took the headset off when the shark had taken the bar off. It just shows how real PlayStation VR is,” Ephraim says.

So does he think there a chance of VR gaming being medically unsafe?

“I think people just have to choose (based) on what their tolerance is, just like with movies and a lesser degree books. It’s another form of entertainment that will deliver a broad spectrum of emotion-evoking experiences so it’s up to the consumer to choose. It’s just like gaming, just like movies, just like books; it’s horses for courses.

“There will be ratings, there will be warnings about the content, just like movies.”

Michael Kasumovic, a gaming expert at the University of NSW, says virtual reality can seem very real even when the graphics are not very rich because it envelops all of your vision.

It certainly can trigger bodily reactions.

“We’re still really early on with this technology. Right now it’s only using our visual senses, but further on in we’ll be able to touch, smell and hear things in three-dimensional space. That’s going to be even more realistic.”