SolidEnergy Systems, Oppo, Tesla and others adding life to batteries

In the near future, your phone and even car battery will seldom go flat, and recharging will take only minutes.

If there’s emerging technology that should warm the cockles of consumers’ hearts, it’s advances in battery technology. And it’s going to have an impact in many areas.

Batteries in smartphones will last much longer and charge incredibly quickly. They will give us even more mobility.

This technology will finally enable phones to reach their potential as high-end multimedia communication devices, and you will also enjoy much improved battery life in tablets, notebooks, wearables, electric cars and drones, even with heavy usage.

Developments are coming from several sources. This month Massachusetts Institute of Technology spin-off SolidEnergy Systems said it was ready to commercialise an anode-free rechargeable lithium battery that would double the time of current lithium ion batteries.

“With two times the energy density, we can make a battery half the size, but that still lasts the same amount of time, as a lithium ion battery. Or we can make a battery the same size as a lithium ion battery, but now it will last twice as long,” says Qichao Hu, a former MIT student and chief executive of SolidEnergy Systems. The breakthrough was reported in MIT News.

The publication says the substitution of graphite used as anode material for a thin lithium-metal foil offers more energy capacity. A different electrolyte enables the lithium batteries to be rechargeable and safer.

This is great news for the electric car. Hu predicts that instead of travelling, say, 320km on a single charge, you will be able to go twice the distance, making it easier to recharge on long road trips.

SolidEnergy batteries for smartphones and wearables may be available by next year.

Others are on longer time frames: Samsung last year revealed it was developing silicon cathode material that would double battery life. It is expected to be available in two to three years.

Nanowire batteries coated with manganese dioxide and an electrolyte gel could last 30 times as long as regular batteries; there are fuel cell batteries that, according to their manufacturers, offer up to a week’s charge for a phone; an aluminium graphite dual-ion battery has been developed in China, as well as another one that charges and discharges with the aid of bacteria.

Battery prices, too, are plummeting.

Phone makers, meanwhile, have been striving to tune the performance of handsets for better battery performance. Apps running in the background on smartphones are more carefully managed, and users have greater control over them.

Manufacturers are increasingly avoiding the highest specced Quad HD phone displays — which suck more juice — except where it is a signature feature.

Then there’s fast charging. If very long battery life is not an option, at least you can top up quickly. At the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona this year, Chinese phone maker Oppo said its phones in future would feature a 2500mAh battery that could be charged in 15 minutes. Its R9 model already offers a 70 per cent recharge in 30 minutes.

At the same event, Israeli start-up StoreDot demonstrated how a modified Samsung phone could be recharged from 5 per cent to 100 per cent in five minutes.

This is not a total surprise. In lab testing last year, StoreDot was seeking to build batteries that fully charged a smartphone in 30 seconds, and electric car batteries that could charge from empty in five minutes. Samsung Ventures is one of its backers.

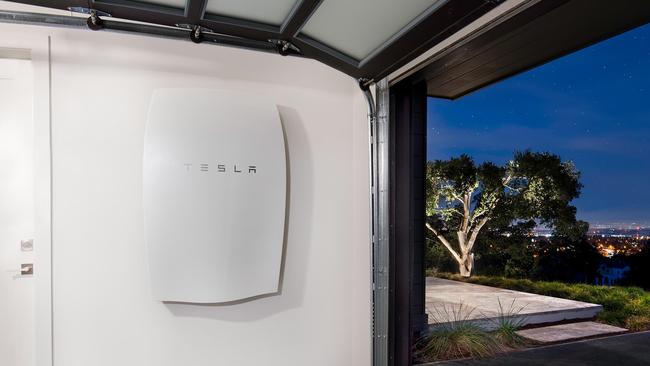

The battery revolution is also invading our homes. Elon Musk’s Tesla, German firm Sonnen and Simon Hackett’s Redflow locally offer home battery solutions for storing solar energy. Samsung, LG, Panasonic and Enphase also are in this space.

In Sydney the first family to install a Tesla Powerwall system says its $40.46 mains power bill in the June quarter represented a 90 per cent drop from $660 in the same quarter the previous year.

If that is a consistent trend, the expenditure could be recuperated in six to seven years. Consumer advocacy group Choice says it could take up to 24 years to get back what you pay for a Powerwall, but it depends on how power is used (storage or load shifting) and how much is stored, consumed on the spot or returned to the grid.

Natural Solar, an installer of Tesla batteries in Australia, says it has had more than 33,000 inquiries since January and sold more than 1000 systems in the same period. “These numbers are expected to grow exponentially as consumers learn more about battery power and there are further innovations and developments in this space,” managing director Chris Williams says.

Home battery solutions will profoundly alter the makeup of the power grid. In Australia this is starting to happen. This month energy retailer AGL announced a trial in Adelaide of a virtual power plant. About 1000 connected batteries were installed in homes and businesses in South Australia. They will provide 5 megawatts of peaking capacity.

For most of the time, including peak use times, consumers use power from their solar panels and batteries, but AGL says that at other times the batteries can be directed in unison to discharge to the grid in a way that offers a consistent power source.

The CSIRO is exploring a similar concept called a virtual power station. In tests beginning in October at Yarrabilba, Queensland, five houses will be fitted with home batteries while another 15 will have inverters — devices that control power storage. CSIRO will be able to switch the inverters on and off to create a reliable power source that can supplement a base-load generator.

Most of this battery technology depends on the availability of lithium, thought to be one of three elements produced after the big bang. Could lithium compounds become the new gold of the 21st century, the key conduit of natural energy storage? And would smart people be setting their sights on lithium mining and investment as we transitioned from fossil fuels to sustainable energy forms with lithium-based energy storage?

South America is a main source of lithium, with compound deposits in Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, as are Tibet and Qinghai in China and Nevada in the US, and there are local deposits in Western Australia. It is estimated the oceans hold about 230 billion tonnes of lithium in compound form. Lithium compounds also occur naturally in the Earth’s crust.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout