Kids are well schooled in eating habits

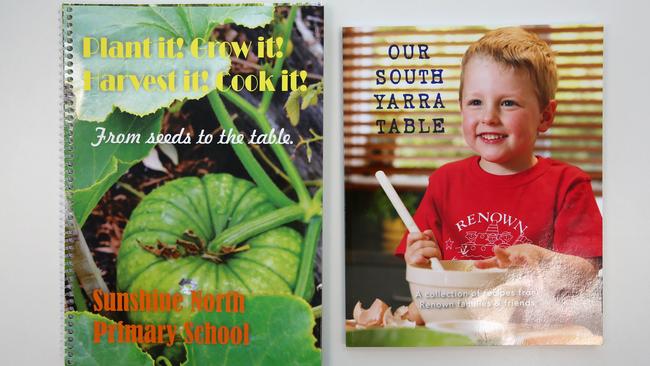

Stephanie Alexander’s program to help schools grow and prepare good food has evolved into self-published cookbooks.

How sophisticated is children’s food, really? Serve a tray of frogs in ponds at a party and they’ll be happy on a sugar high, right? Stay away from the vegies or hide them in a shepherd’s pie.

Not to mention the unvarying sandwiches of primary school — Vegemite, ham, peanut butter (if it was allowed) and tuna (if you didn’t mind other kids calling you stinky).

How things change. Now, it seems the kids have all grown up and gone gourmet, judging by the latest range of school cookbooks featuring kale, nasturtium flowers and truffle oil.

Sunshine North Primary School, in Melbourne’s northwest, recently published a multicultural cookbook with recipes for wonton soup, avgolemono, meringues and Thai corn fritters. Not unexpected, perhaps, for a school with 23 different nationalities.

The school has been part of the Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden program since 2007 and while it is unlikely they grew the truffles for their risotto in the school’s garden, the parsley and onion probably grew there.

Principal Ken Ryan says the school started from a challenging nutritional position, with many students coming from low socio-economic backgrounds.

Parents would drop off Happy Meals from McDonald’s at lunchtimes or the students would pop out to the nearby fast food outlets themselves.

Since the school moved lunchtime to 11am and introduced the kitchen garden program, however, parents have taken note, with newly popular items including fresh fruit and traditional Vietnamese fare.

Ryan says parents place faith in teachers and the cookbook was a way of showing what that faith had produced.

“So many parents are so busy and don’t know what’s happening in the school,” he says.

Many of the children go home now and help with washing dishes or cooking thanks to the skills they’ve learned.

“It’s not about healthy food, it’s about good food,” he says.

Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden Foundation chief executive Ange Barry says the school cookbooks give insight into the students’ diverse cultural backgrounds and particular interests. One of the biggest impacts of the program was on vocabulary, as children start to learn the names of different varieties of tomatoes and learn the meaning of “heirloom” vegetables.

“The experience they have at the supermarket can be a bit generic,” she says. “Once they find out there’s such thing as a purple carrot, they want to grow them.”

Kids also love the idea that they can eat flowers (or some flowers, at least), and that helps develop a sense of adventure and willingness to try new things.

The kitchen recipes vary from school to school, with the produce changing according to the region.

An unintended consequence of the program is that the parents end up learning new skills, too: in one instance, a parent came to a school to ask how to cook jerusalem artichoke because their child had been talking about it.

Hence, the impetus for schools to publish their own cookbooks.

“It’s not MasterChef,” says Barry. “It’s what should be common and basic knowledge.”

And proving you’re never too young to learn a love of fine food, Renown kindergarten in South Yarra published a cookbook late last year with the help of parents and local businesses.

Children might want to ask the grown-ups to hold the chillies in the recipe for medhu vada from India — or maybe not?

Parents had better watch out, in any case: Camille from Sunshine is now a lover of gnocchi with “noisette” butter and sage, possibly followed by a dessert of meringues with stewed plums.

Yum. Hang on while I photocopy a few of these pages …