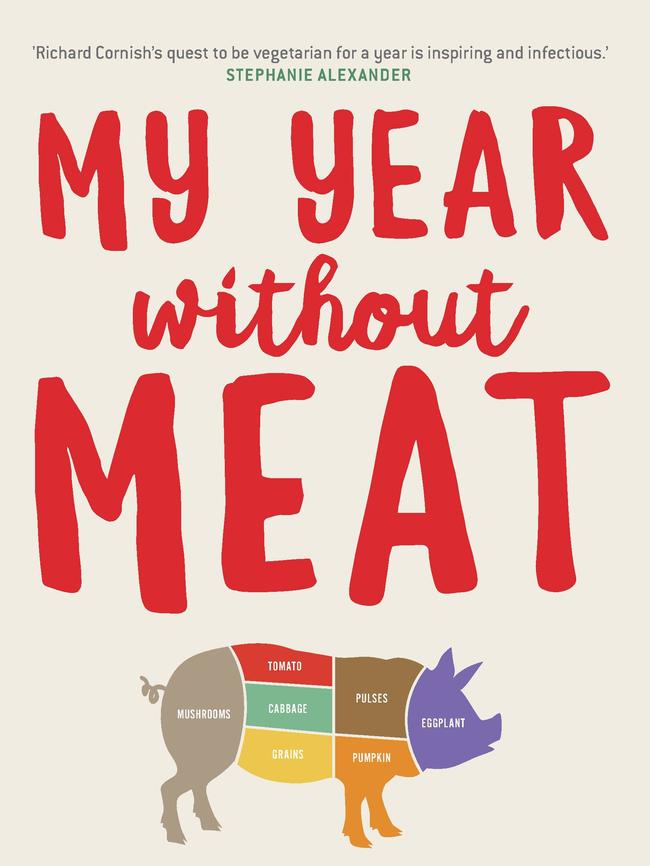

Extract: My Year Without Meat

Jamon in Spain is not just air-dried ham. Eating jamon is a patriotic act.

Spaniards eat a lot of meat. The average Spaniard consumes 118kg of flesh each year, a sixfold increase since the dark days of the Franco era, when they existed mostly on seasonal vegetables and around 50g of meat per day.

Today, Spaniards eat more than 300g of meat a day. Their industrially raised chicken is really good compared with the bland $10 chicken we see here. In the centre and north of the country, Spaniards also eat a lot of lamb, and game in season, and throughout the country seafood, jamon and pork appear in almost every dish.

Jamon in Spain is not just air-dried ham. It is not the Spanish equivalent of prosciutto; it is much more than that. Eating jamon is a patriotic act, something one does when one is truly Spanish. This has its roots in the 15th century, when publicly eating pork was a culinary shibboleth, a tacit act to prove to everyone watching that one was neither a Muslim nor a Jew.

From the fat rendered from chorizos spread on toasted bread at breakfast, to the lard used in pastries made in convents, to the chunks of pork and jamon that sit in legume stews such as cocido and fabada, pork is king in Spain. Long live the king.

Asking for a meal without meat in Spain is greeted not with contempt but puzzlement. “Why would you not eat meat?” is asked politely. This attitude comes from a people for whom starvation during the Spanish Civil War is still within living memory. Thousands died from want of food. Countless thousands more fled to the hills and lived on food foraged from the wild.

This understanding of poverty has resulted in food waste being a non-existent problem in the traditional kitchens of the south, where there is a use for anything that is edible. Tiny bits of jamon, such as the bone and the skin, are used in dishes to create flavour, texture and nutrition. Every single part of the pig, as well, is used in the kitchen after slaughter. In a bar in Extremadura, several years before this visit, I was served a tapa plate of pickled pigs’ tails sprinkled with local smoked paprika. That was it. Pickled pigs’ tails. In Calle de la Cruz in Madrid, there is a bar that specialises in flat grilled pigs’ ears and sweetbreads called La Oreja de Jaime. In Australia we’d call it Jamie’s Ears.

* * *

After some time spent on the sunny Mediterranean, we were heading up to the region of Huelva, northwest of Seville. We were driving there to explore the lore around la matanza, or the killing of the pig, and to speak with the maker of one of the best jamons in the nation.

Domingo Eiriz is the sixth generation in his family to make jamon. He is the youngest son, gregarious, social and professional. All the pigs for his factory are raised around the area, and sent away to be slaughtered and dismembered in another town that has the abattoirs. The bits are trucked to the factory in this little town of 600 or so, and reassembled and given another life as embutidos y jamones. Smallgoods and jamon.

Domingo led us through the sausage drying rooms with their forest of lomos, strips of loin muscles, hanging from racks. We walked towards the inner sanctum, los secaderos de jamon — the jamon drying rooms. We ducked as we entered a low-domed ceiling room, open to the outside world through shuttered windows. We gasped but the sound disappeared, absorbed by the irregular shapes of the hundreds of jamons hanging silently from the ceiling. Their flesh was wine red, their skins gouda yellow, all decked with dark spots and patches of grey and white mould. These were two years old. They were some of the best hams made in Europe. Deeper tasting and considered more masculine than the pinker prosciutti of Parma, these would sell for many hundreds of euros across Spain and around the rest of Europe.

“You must understand that making jamon is a very special process,” says Domingo. “It is a battle defending the jamon from the putrefying bacteria by curing it with salt and drying it in the mountain air.

“At the same time we are also creating a fertile place for the beneficial moulds and enzymes that transform the meat proteins into very delicious salt crystals that embed the flesh,” he says in wonderfully considered English. “Basically jamon sits somewhere between mummification and transubstantiation. It is a miracle.”

With his long round-ended blade, fine like a fish knife, Domingo delicately cuts into a three-year-old jamon. The old kitchen — made of stone, with dark oak beams supporting the white roof — was filled with the aroma of some of the best sliced ham on the planet. Nuts, sweet old flesh, mushrooms. Mo Vida chef Frank Camorra was waiting quietly to one side. Cesc Castro, our researcher and great friend, was hovering nearby. He is Catalan and, by birth, should be immune to the seductive powers of Andalusian jamon. Our photographer and another good friend, Alan Benson, was quietly taking his images. I watched both of them. They were oscillating closer and closer to the plate that Domingo was preparing for us to shoot.

I was watching Frank eat jamon. He loved it. He was holding the lonchas (small rectangular slice) gently, his thumb and forefinger pinched, and raised it above his mouth. He angled his head slightly and laid the jamon on his tongue. He chewed a little, smiled and nodded approvingly to Domingo. Domingo smiled too. He knows the effect his jamon has on people.

He passed the plate around. Cesc and Alan repeated the process. Cesc gave a wry half-smile and nodded. Great praise from a Catalan. Alan took a piece, chewed, smiled and nodded his head from side to side as he chewed and tasted. “Good,” he says. “Excellent.”

Domingo passed the plate to me. He didn’t understand that when I held up a hand I was suggesting that he pass it back to Frank. He pushed it forward. The fat was creamy white. “Come,” he says, “eat.” The flesh was ruby red. “Try some.”

I could smell nuts and mushrooms rising from the plate. “It’s good,” he says. There were small white salt crystals in the flesh that I knew would crunch between my teeth and release a wave of umami. “You must,” says Domingo. The ribbon of fat was as wide as a butterknife, the loncha as thick as a communion wafer.

The fat seemed to draw the heat from my tongue, like a tablet of excellent chocolate. The aroma was subtle yet complex, like perfume applied in the morning worn well into the afternoon. Faded roses, forest floor, champignons, a punch of pork, aged pork and oak, something decayed but in the best possible way. This was held together by a backbone of salt, a clean lactic tang, and round and lingering savouriness. It was possibly the best piece of flesh I had ever eaten. In a rapid piece of self-reconciliation I knew that my time of penance and reflection was over. That jamon was a work of art. I had crossed a threshold and there was no going back. My Year Without Meat closed with a single loncha of jamon iberico de bellota.

Broad beans with jamon

The day after I ate my first piece of flesh in more than 12 months I was offered this very simple dish. I was in the Sierra de Aracena, a great swath of hills in western Andalusia still covered in oak forest. It was early spring and there was still a dusting of snow on the peaks. The first of the broad beans were in season. Served with a little jamon for salt and succulence, they were just stunning. The local broad bean season will start shortly.

1kg whole young broad beans, removed from the outer pod | 20ml extra virgin olive oil | 100g jamon, chopped into medium dice (rolled pancetta can substitute) | 2 shallots/scallions finely chopped | 40ml white wine

Bring a pot of salted water to the boil and blanch the broad beans for one minute. Refresh in cold water. Drain and set aside. In a heavy-based pan, heat the olive oil over medium heat and add the jamon. Cook for five minutes until slightly brown. Add the chopped shallots and cook for five minutes until transparent and beginning to become golden. Turn heat to high and deglaze the pan with the white wine. Return the beans and warm through for a minute or so. Serve with baked fish, chicken or loads of seasonal vegetable dishes.

An edited extract from My Year Without Meat by Richard Cornish (MUP, $29.99), out now.