First look: Inside the 7th TarraWarra Biennial

Esteemed art curator Nina Miall will propose a fresh approach to the national survey, when her iteration of the TarraWarra Biennial, Slow Moving Waters, opens at the regional Victorian museum this weekend.

The smell of toffee cooking fills the air inside the TarraWarra Museum at Healesville, about an hours’ drive from Melbourne. It’s not coming from the adjacent restaurant, a popular destination for city day-trippers, but from the museum’s basement.

It’s down here that Lucy Bleach, one of the 7th TarraWarra Biennial’s 25 participating artists, has been busy embalming a double bass with layer upon layer of the hot, sticky candy, as part of her interdisciplinary work attenuated ground (the slow seismogenic zone), 2021.

“It’s quite a fine art,” acknowledges Nina Miall, the esteemed Australian curator who was tapped to guest curate this year’s TarraWarra Biennial.

“The idea is that the toffee will gradually liquefy and slump off over the course of the exhibition,” she explains.

It’s just one of the works that encourages the viewer to embody the ideas the show is built upon, namely slowness, deceleration, drift and the elasticity of time.

Miall had been ruminating on these concepts for a while, but it wasn’t until she learnt the accepted translation of the local Woiwurrung word, ‘tarrawarra’, that the exhibition started to take shape.

“It means slow-moving waters,” explains the curator. “It refers to the particular passage of the Birrarung — the Yarra River — that meanders around the southern end of TarraWarra Estate.”

The TarraWarra Biennial will be the talk of the art world when it opens to the public this weekend. This is partly due to the exhibition’s physical format, a luxury most of the globe’s biggest cultural institutions still can’t pull off. The structure of this biennial, and the museum that hosts it, is also fairly unique.

Built by Australian philanthropists and art collectors Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AC in the early 2000s, who established it as a not-for-profit charity with a constitution and independent board of directors, TarraWarra became the first art museum in Australia to be supported by a significant private endowment. Unlike many national surveys of this scale, the TarraWarra Biennial, which was inaugurated in 2006, is curated by a different independent curator every year.

What direction Miall will take this edition of the biennial in has been another source of anticipation among the arts community. One of the country’s most exciting curators, she’s held top positions at London’s Royal Academy of the Arts and Singapore’s acclaimed Future Perfect gallery.

From 2012 to 2017 Miall was the curator at Carriageworks, where she launched the inaugural edition of another successful biennial: The National: New Australian Art. Her interest in socially engaged art that responds to the specific environment it’s created or exhibited in makes her partnership with TarraWarra, which is set among the hills of a working vineyard on Wurundjeri Country, all the more intriguing.

“Nina Miall is one of the most respected curators in Australia,” said TarraWarra Museum director Victoria Lynn, of Miall’s appointment.

“The wealth of her experience speaks to TarraWarra Museum of Art’s desire to present Australian art in a global context.”

When Miall signed on to curate the biennial in 2019, it was slated to open in August 2020. When it became clear the exhibition wouldn’t be going ahead on schedule, a part of the curator was relieved.

“It was beginning to feel like we were betraying the spirit and ethos of the exhibition, because things were moving really fast,” she recalls.

“In a way, it felt fitting that it was postponed. We were forced to really slow down and do things deliberately and consciously. Slowness was built into the exhibition by chance just as much as by design.”

While the exhibition ground to a halt, the ideas explored by the artworks in it seemed to gather a sense of urgency.

Roughly a third of the participating artists are Indigenous, and the urgent preservation of First Nations knowledge systems — a conversation Australia became especially gripped by last year — weaves its way through many of the works on show.

Palawa artist Mandy Quadrio’s sculpture Whose time are we on?, 2021, is one such work. Crafted from steel wool, its abrasive sinews represent colonialism’s systematic scouring of her people’s sovereignty.

The degradation of the natural environment is another recurring theme.

Senior Wurundjeri elder Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO, who gave the Welcome to Country at the museum’s official opening in 2003, worked with Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones on Making the Birrarung, 2021, a constellation of cast bronze mussels that have been arranged throughout the museum so as to replicate a nearby stretch of the river. Miall points out the mussels used to be a vital part of the local river ecosystem, “but their numbers have depleted in recent years because of introduced toxins, pests and faster flowing currents”.

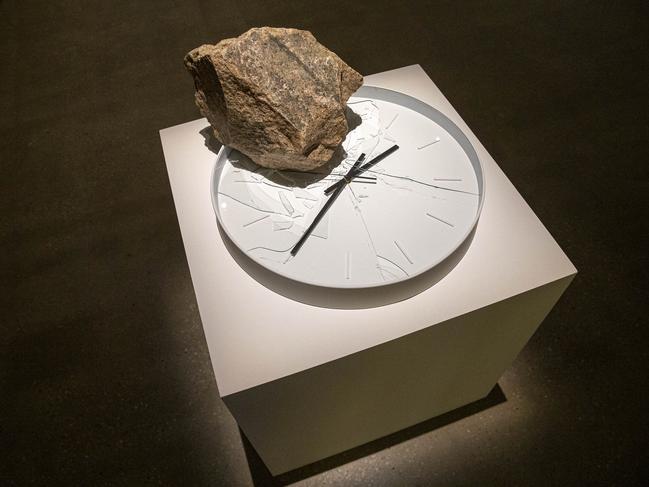

Nearby, a sculpture by Melbourne-based multidisciplinary artist Jeremy Bakker called On Time, 2017, invites onlookers to confront their relationship with time, and the onus modern life puts on keeping track of it.

“It’s this large clock that’s had its glass face punctured by a piece of granite, so it’s stopped in time,” Miall says.

“The only thing that keeps ticking against the mass of the rock is the clock’s second hand. But it never gets anywhere. It’s the first thing you encounter when you enter the space and it gives this sensation of time being arrested, which is a nice opening statement to the exhibition, I think.”

Other works in the exhibition explore alternative ways of mapping time; Sydney-based artist Michaela Gleave’s work, The World Arrives at Night (Star Printer), 2014, is programmed with the map coordinates of TarraWarra. Once a minute, it prints out the details of a star that’s appeared over the horizon.

“Michaela’s is one of the works that will unfold throughout the duration of the exhibition,” Miall tells The Australian. “It’s been designed to reward multiple, extended visits, because every time you come you’ll see something different.”

The TarraWarra Biennial is, technically, a national survey of contemporary Australian art. But Miall, who’s opinionated in a very considered manner, admits she finds the term increasingly problematic.

“The idea of the ‘national survey’ has become quite a fraught concept,” she says.

“It’s very difficult to represent the breadth and depth of the experiences in this country in a single exhibition.

“Invariably, there are omissions. It’s only my perspective, and it’s impossible for me to have an in-depth knowledge of the entire country.

“What purports to be national surveys can actually be very partial, and they can end up looking more or less like another.”

As an alternative, Slow Moving Waters proposes a large-scale exhibition made up of artists from all over Australia, whom Miall and the museum have given the opportunity to engage with the location and surroundings of the exhibition in some way.

“I spent a long time working in London with artists who were in Mumbai and Shanghai and Montreal. I was on a plane every week and very much immersed in that international biennale circuit,” reflects Miall.

“Obviously, Covid has put paid to that. But even before the pandemic hit, it felt like there was this real shift happening in the arts towards the local, and what ‘local’ means.”

The curator recalls a recent trip to the remote Indigenous community of Yirrkala, in northeast Arnhem Land.

“I was part of a delegation of art historians who spent some time up there reflecting on post-national histories, and working in a way that takes account of the local as much as the global,” she explains.

“It really informed my thinking in terms of connecting the Biennial to place and context.”

An impressive number of the works Miall commissioned for Slow Moving Waters have emerged from residencies that were completed in the community surrounding TarraWarra.

Multidisciplinary artist Yasmin Smith spent time working with the Estate’s viticulturist, the materials she came across in the vineyard inspiring the archaeological nature of her ceramic installation, Terroir, 2020.

Brisbane artist Caitlin Franzmann also immersed herself in the biodiversity surrounding the museum, her rigorous collecting and recording of material and immaterial forms informing to the curve of you (TarraWarra), 2021, an experiential sound work that takes participants on a guided walk around the museum’s grounds.

Miall calculates that three-quarters of the exhibition is made up of new commissions, a feat she’s particularly proud of.

“There’s a lot of talk about the aesthetics of care in the arts at the moment, and as a curator who’s helping to translate an artist’s vision for an audience, I take that responsibility quite seriously.”

She says it’s vitally important that bigger exhibitions like the TarraWarra Biennial commission artists to make new works, especially here in Australia, where “it’s one of the few ways artists can be sustained”.

“There are a number of artists in this exhibition who don’t have gallery representation; who don’t have those formal channels through which to sell their work,” she says.

“There are artists from all stages of their careers — from artists who left art school probably only five years ago, to a very senior Maḏarrpa artist from northeast Arnhem Land, Noŋgirrŋa Marawili.

“What I’ve tried to do with the exhibition is have many different perspectives. Many different voices that really explore ideas of slowness and drift, deceleration and delay in many different ways.”

The approach says a lot about Miall’s unique curatorial vision, which has enabled her success both here and overseas. Rather than setting out to get the buzziest names on her bill, she’s more interested in arranging a show that people will come to, leave, come back to and leave again feeling challenged, contemplative and maybe even changed.

Slow Moving Waters will show at the TarraWarra Museum from March 27 – July 11 2021; twma.com.au.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout