Chris Kenny: the day I played lawyer and won

I am in Magistrate’s Court 5.1 at Sydney’s Downing Centre and finally putting to good use those hours of watching LA Law.

“Perhaps I could assist the court, your honour?” Frankly, it was fun just hearing the words come out of my mouth. I had to suppress a smug smile that would betray how much fun I was having — this, after all, was serious.

Here I was playing at being a barrister, representing myself in court and anticipating the chance to put some familiar phrases to good use. It was all I could do to stop myself referring to my adversary, the prosecutor, as “my learned friend”. Wisely, perhaps, I scaled it back a notch as I tried to help sort problems playing the video evidence on a big screen. “Your honour, I would be happy for my friend here,” I venture, nodding to the prosecutor, “to show you the video on his laptop as I have already seen the evidence.”

We were in Magistrate’s Court 5.1 at Sydney’s Downing Centre and I was contesting a road traffic charge. This was thoroughly intimidating but exhilarating — like a first date with your future wife or playing a football final.

Finally I was putting to good use those hitherto wasted hours of watching TV shows such as LA Law, Rake and Ally McBeal — not to mention occasional reporting on court proceedings as a journalist.

The wheels of justice are in no hurry; I cut short a trip to Perth to make the first appearance, fully prepared to argue the case, but was forced to wait more than an hour simply to enter a plea and be given a date months later. Sitting in court, waiting your turn, you watch a passing parade of traffic and minor criminal matters. The magistrates strenuously encourage people choosing to represent themselves to seek advice from a duty barrister, and if they face photographic evidence most are wisely advised to plead guilty with extenuating circumstances to lessen any penalty.

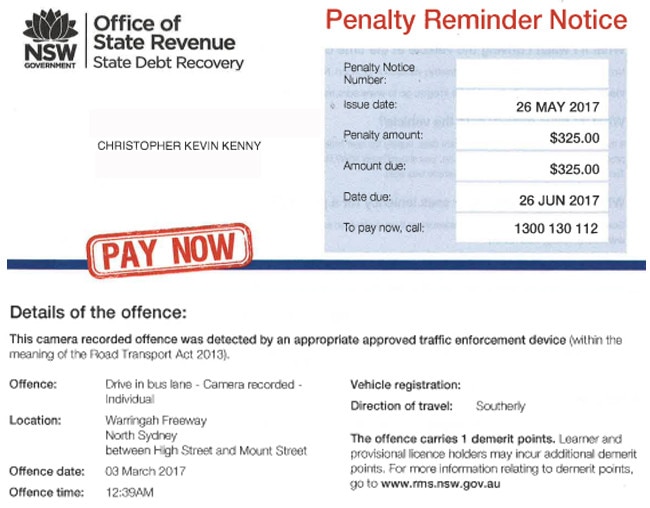

My case was about a $325 fine that arrived in the post for “drive in bus lane” with photographic evidence. When I checked the pictures online, sure enough, there was my car, late at night, heading south on the approach to the Sydney Harbour Bridge, in a bus lane.

I realised immediately the only reason I was in that lane was because I had been diverted by signs and barricades used when they shut the tunnel late at night for maintenance. It had happened a few times when I was driving home from my Heads Up program on Sky News.

Surely it couldn’t be an offence to be in a bus lane when the traffic directions forced you into it? I Googled the legislation. Sure enough, under the Road Rules 158 (1) there are a range of conditions, such as entering or leaving a road, where you can drive in a bus lane for a “permitted distance” of 100m. And under 158 (2) it was clear you could drive in a bus lane to avoid an “obstruction” with no reference to a “permitted distance”.

Cranky about being fined for doing the right thing and driving safely, I was confident I could take it on. There was no reference to distance in my fine but if they presented any evidence to prove I was in the lane for more than 100m I was confident 158 (2) should save me: the lanes to the tunnel were blocked by a traffic management “obstruction” and I was forced to drive across a bus lane to get across the correct lane for my bridge crossing.

Morally right, happy with my legal basis, I relished the challenge of playing lawyer.

At my first appearance the magistrate double-checked whether I intended to persist with my not guilty plea. I did. “Have you received legal advice?” she asked. “Informally,” I fudged (I’d mentioned it to a lawyer friend, who laughed knowingly and left me to my own devices). The magistrate could tell I was serious and set a date.

On the day, I had the chance to walk the prosecutor through my case in an informal discussion. I thought this would prompt him to drop the charge, but when it was called he proceeded at full throttle. He even insulted me by arguing I had provided no proof that the tunnel had been closed that night.

I am not the sort of person who takes kindly to any insinuation of dishonesty, so I retorted sharply, explaining it was the only reason I could have been driving in that situation and suggesting the traffic authorities ought to be the ones to communicate when the tunnel is closed so that people weren’t unfairly hit with these fines. His barb increased my determination. Now, it was personal.

His ridiculous angle was crushed when the magistrate noticed a sign on the video that indicated the tunnel was closed. Take that, my not-so-learned friend.

I relished the chance to sum up my case, indicating that neither the fine nor the demerit points posed serious problems to me but, rather, I was here to prevent an injustice. I was not going to pay a fine for obeying the traffic directions and the law.

As the magistrate summarised the evidence in some detail, the tension built and the themes from LA Law and Law & Order were competing in my mind. Then came the wonderful words that took a moment to sink in: the charge was “dismissed”.

I wanted to punch the air. Instead, I said, “thank you, your honour”, bowed my head and turned to leave. I attempted to give a nod of sporting acknowledgment to the prosecutor but he averted his eyes. Goodbye, my learned friend. I bounced out of court eager to tell the world and find out if there was any way I could sit the bar exam.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout