Chelmsford doctors fight to expose role of Scientologists

Two doctors say an investigation into Sydney’s notorious Chelmsford Private Hospital was torpedoed by Scientologists.

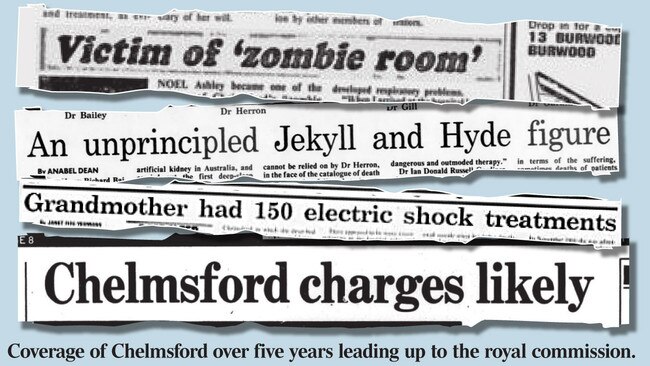

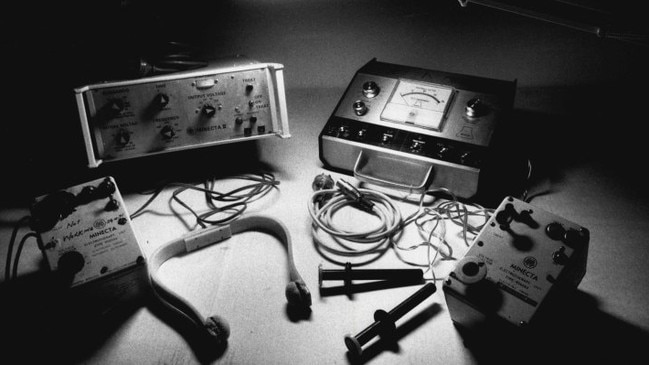

They called it the “zombie room”, the ward at Sydney’s notorious Chelmsford Private Hospital where psychiatric patients lay side-by-side in a drug-induced “deep sleep”. The treatment, which also involved electro-convulsive therapy, was linked to 24 deaths and condemned by a royal commission 30 years ago.

Now, two surviving Chelmsford doctors, John Gill and former psychiatrist John Herron, are seeking to convince the Federal Court that the two-year royal commission was led astray by Scientologists. The doctors, elderly and with little to lose, want to up-end the long-accepted view that what occurred at Chelmsford was a medical scandal.

In doing so, they are also seeking to slay another Australian sacred cow: that royal commissions — which cost eye-watering sums and are being ordered with increasing frequency — are the best way to establish the truth about wrongdoing and how to tackle it.

The men have launched defamation action over a book they say revealed all the “tricks” of Scientologists but perpetuated the church’s misinformation in relation to events at Chelmsford between 1963 and 1979. The case has focused attention on the nation’s outdated defamation laws, which contain fewer protections for public-interest journalism than those of other countries.

The book by ABC journalist Steve Cannane — Fair Game: The Incredible Untold Story of Scientology in Australia — included a chapter on Chelmsford because the church was central to exposing what occurred there. In it, Cannane reveals what the doctors were unable to establish at the royal commission: that Scientologists planted a nurse at the hospital, Rosa Nicholson, to obtain footage and steal patient files. Church members also played a key role in feeding information to the media and pushing for a public inquiry.

Cannane’s book made clear that the church would stop at nothing to rid the planet of psychiatry. In England a directive was given to discredit the profession by placing a “bad mark” on every psychiatrist — such as a murder, assault or rape. Cannane’s thesis was that Chelmsford was a rare instance in which the Scientologists had used their underhanded tactics as a force for public good.

But Gill and Herron are now trying to show, decades on, that the Scientologists interfered with evidence and manipulated witnesses — and possibly sabotaged their work at Chelmsford in other unknown ways — as part of their campaign against psychiatry.

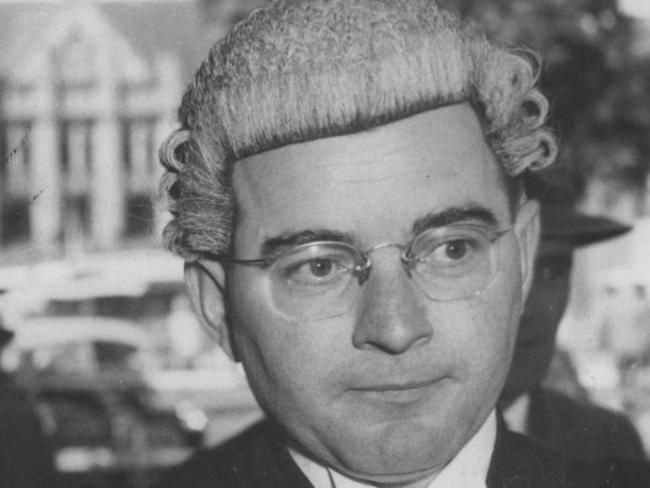

For those who followed coverage of the royal commission and came to remember it as something of a horror show, the men’s position is that the deep sleep therapy led at Chelmsford by psychiatrist Harry Bailey was not dangerous or experimental but accepted at the time and administered under proper supervision. It’s a proposition the defence argues is “absurd”. Cannane and HarperCollins — owned by News Corp, publisher of The Australian — are now being put to the huge expense of a six-week trial, with legal bills expected to run into the millions. They are effectively required to prove the truth of matters that were the subject of royal commissioner John Slattery’s findings.

Revisiting the past

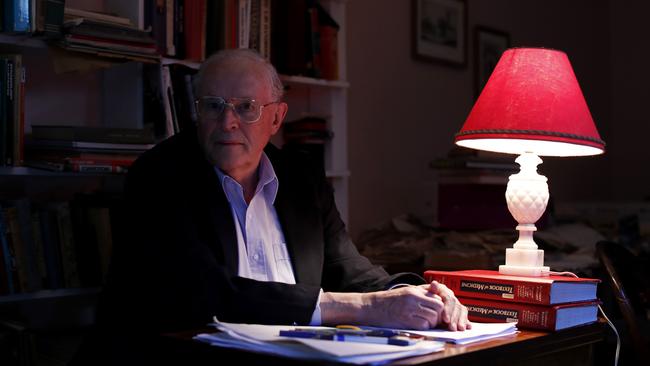

Gill, now 78, and Herron, now 87, argue that until the book’s publication, events at Chelmsford had been laid to rest. The pair had moved on with their lives. Herron, who was deregistered in 1997 for reasons unrelated to Chelmsford, had moved to the NSW central coast, had taken up woodworking and had a busy social life. Gill, who lives in Sydney’s leafy northern suburb of Wahroonga with his wife of 53 years, had continued work as a GP.

The book brought back all the trauma and shame associated with those events, they say. Herron says it contributed to his wife, Margaret, suffering a fatal stroke. Gill told the Federal Court this month that he believed the conclusions of the royal commission were “inaccurate” and “give or take, in line with what the Scientologists thought”.

He said Cannane’s book, too, “adopted the Scientology version of events” in relation to Chelmsford. Under cross-examination by barrister Tom Blackburn SC, Gill said he was “just staggered” and “totally bewildered” by Slattery’s findings against him in 1990 and did “not accept any of them”.

Slattery found that Gill was “a most unsatisfactory witness” who was “prepared to lie when the occasion demanded”, that he was willing to falsify or remove records, and “showed not the slightest remorse or compassion” for the deaths of two patients he treated.

Herron is in hospital due to a fall that occurred when he was part-way through his cross-examination. Before the incident, he told the Federal Court he did not think he “did anything wrong” and that he still defended the deep sleep therapy at Chelmsford, which involved administering patients with large doses of barbiturates to stay asleep sometimes for weeks at a time. “There were thousands of patients, and even if you reduce it to 3000 patients, I think that is approximately two a year,” he told the court via video link. “The death rate in a psychiatric hospital is much higher than that.”

When asked whether he was aware of the toxicity range of some of the barbiturates that were being administered, he said the ranges had been insufficiently researched. “I thought it would be quite safe and I think I did think it quite prudent to try increasing doses and see if it was as toxic as it had been mentioned in the literature,” he said.

Blackburn asked: “You are saying that it was acceptable to take those ranges that appeared in the literature and, what, exceed them in order to test whether they were sound or not?” Herron replied: “How else could it be tested?”

Scientology campaign

The men’s barrister, Sue Chrysanthou, painstakingly highlighted in court this week some of the Scientologists’ links to the media campaign against Chelmsford and the evidence presented to the commission. She suggested to Cannane on Tuesday that Scientologist Jan Eastgate was “heavily involved” in the Chelmsford Victims Action Group, which lobbied for an inquiry; she took statements from alleged victims that were provided to authorities and accompanied at least one former patient to the police. Eastgate delivered medical files to 60 Minutes, whose coverage, presented by Ray Martin, won a Logie award.

The action group also organised for about 50 alleged victims to meet journalists from The Sydney Morning Herald, resulting in two weeks of sustained reporting that triggered the royal commission. Chrysanthou suggested that Eastgate also had a history of coaching witnesses; Cannane had previously accused the Scientologist on the ABC’s Lateline of pressuring a girl to lie about sexual abuse to protect the church, a claim Eastgate denied. At least five witnesses to the royal commission likened Chelmsford to the Nazis’ Belsen concentration camp — an unusual description Eastgate used in relation to other psychiatric hospitals, Chrysanthou pointed out.

The barrister put to Cannane that it was unreasonable for him to rely on the commission’s 4000-page report and that it was a “failing” on his part, as a journalist, not to make any attempt to contact her clients for a response to the book’s allegations.

It’s a charge Cannane rejects. Cannane told the Federal Court that his research focused on the role the Scientologists had played in exposing events at Chelmsford — and he relied on findings made by royal commissioner Slattery to describe what occurred there.

“I trusted (Slattery’s) assessment,” he told the court on Tuesday. “He was an eminent judge … He was given the role of investigating what was going on at Chelmsford Hospital, and I believe that he got to the bottom of it.”

Defamation law

Federal Court judge Jayne Jagot’s ruling on whether it was reasonable to rely on royal commission findings will likely affect the work of journalists in the future. Cannane and HarperCollins tried to have the defamation case struck out two years ago as an abuse of process because the events dated back to the 1970s. Jagot ruled in 2018 that it should proceed and that the doctors had raised “triable issues” under the law of defamation. The defendants are now “being made to prove something that cannot be other than beyond argument … that these treatments were irresponsible, grossly negligent (and) far outside the bounds of any acceptable medical practice”, Blackburn has argued.

They are set to call eminent psychiatrists including Ian Hickie and Gordon Parker to testify about the unacceptable nature of the treatment.

Cannane is also seeking to convince the court that his book was a fair report of royal commission proceedings — a defence attacked by Chrysanthou as “hopeless” — and that it is covered by qualified privilege because he acted reasonably. University of Sydney professor of law David Rolph says the case highlights the fact Australian defamation law does not have a “public interest” defence, unlike Britain, Canada and New Zealand. In Britain, the public interest defence protects the responsible publication of matters in the public interest even if it damages someone’s reputation, he says.

“One of the things about the reform process that is being led by NSW is that there is a movement to introduce a statutory public interest defence,” Rolph says.

“Other common law jurisdictions have gone back and decided that the law took a wrong turn in the 19th century and had not adequately protected publications on matters of public interest.”

For Gill and Herron, the case is a chance to put their side of the story. They argue they were unable to do so at the royal commission — they were not permitted to call witnesses, were limited in their cross-examination and were denied basic legal protections, such as the privilege against self-incrimination and legal professional privilege. Their concerns highlight a limitation of royal commissions, which have grown in recent times to become a quasi-industry and often put forward as an answer to many of society’s ills.

Sydney barrister Margaret Cunneen SC says royal commissions are very different to courts. “You are getting the views of a team of government-appointed people who are not sitting as judges,” says Cunneen, who has led a commission of inquiry and also has been the subject of an inquiry found to be beyond the NSW corruption watchdog’s powers.

“(They decide) what witnesses to call and, compared to courts, witnesses have very limited opportunity to give a full narrative if they have one. They’re asked questions and the subject matters and the limits of them are strictly confined according to the limitations imposed by the royal commissioner.”

During the past 30 years there have been dozens of royal commissions at the federal and state level, on topics ranging from the building and banking sectors to trade unions and the botched insulation scheme. Three are under way at the federal level into aged care, disability services and natural disaster arrangements.

They have cost taxpayers and participants billions; the royal commission into institutional abuse alone cost taxpayers more than $370m, while the banking inquiry cost about $70m.

Institute of Public Affairs research fellow Morgan Begg says royal commissions should be a “last resort” for parliament to find facts in a specific area because they ignore the rules of procedural fairness required in normal courts.

“Too many politicians see launching a royal commission as a political win and a person’s appearance before one as proof of their wrongdoing,” he says.

The allegations against Gill and Herron have never been properly tested by a court. Slattery referred both men for possible criminal charges and disciplinary action in 1990. They had already faced disciplinary action before the royal commission but had the proceedings permanently stayed in 1986 as an abuse of process because of the 13-year delay in bringing proceedings. They also succeeded after the royal commission in having further disciplinary action stayed and Gill had two manslaughter charges stayed because of the delay. However, former Chelmsford patient Barry Hart, whose story Cannane tells in his book, successfully sued Herron for negligence, false imprisonment and assault and battery, and received a small payout in 1980.

Gill’s and Herron’s bid to clear their reputations after all these years is a long shot — but they’re hoping to emerge from their own 50-year nightmare.

Additional reporting: Chris Merritt

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout