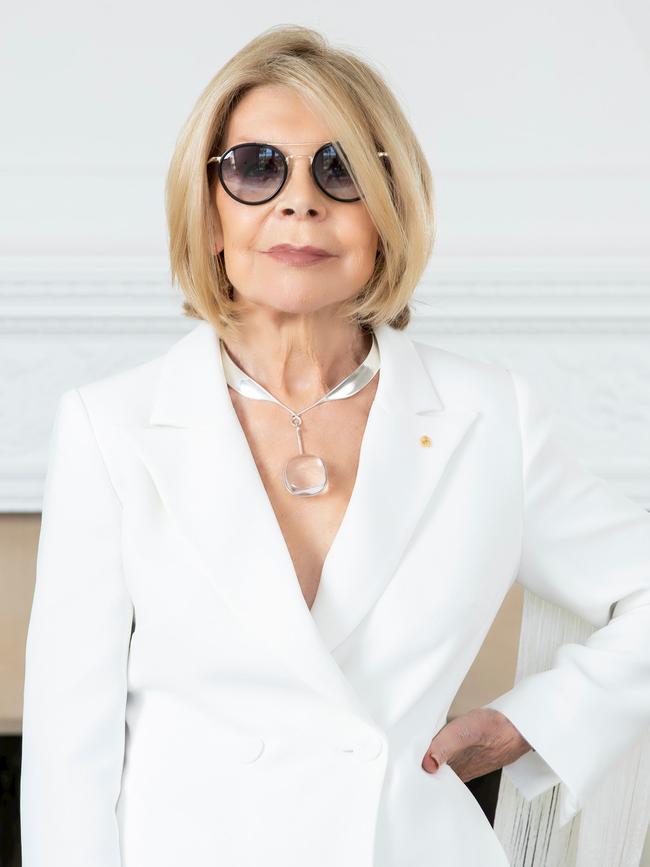

Carla Zampatti’s lasting lesson for daughter Bianca Spender

As Bianca Spender celebrates 15 years since the launch of her label, she reflects on what it meant to forge her own path.

Mum was an incredibly inspiring woman, but it was more about what she did than what she said. She never had an opinion about what I should do in life, just that I should work hard and be passionate about what I did. She led by example. That was the school of Mum.

She had a lot of joy in work; she wanted us to find the joy and passion in working hard. When I talked about fashion, she was like, “Well, you better be passionate … It’s tough.” I knew it, and I didn’t go in with any sense of ‘You’ll be in the family business.’ She was a realist. She knew what it took to survive in fashion.

I was always experimental with clothes and had a very distinctive sense of style. The whole time I’d been at uni studying commerce, I was working in Mum’s business. I was allowed in the design room because I was good at cutting; I’m very precise. There were two amazing drapers, they would get a roll of fabric and a mannequin and start that way. It wasn’t a drawing, you weren’t trying to emulate something. You were reacting to the fabric, and whether it was falling on the bias or playing with the drape or twisting and turning and then making these cuts. Very quickly I learned that was my love. There’s something about seeing how things unfold on the fabric and the body.

After two years, I was coming up with ideas that I didn’t have the craft to render. I had learned in Mum’s office, but I also knew I had, in a way, learned as much as I could there and I wanted to go to the heart of draping, so I moved overseas. France is where draping was born, whether it was Balenciaga, Givenchy, Vionnet. I worked for Martine Sitbon for three and a half years. I feel so incredibly lucky to have been part of that environment. The only rule was that you had to push your creativity as hard as you could. My mum ran a business that had an incredible sense of style and design, but she was very astute in her business and Martine was the opposite. I remember saying, “I think that might be a bit complicated for the makers and it’s going to become very expensive.” She said: “We dream first. And then we work out how to make it happen.”

September 11 hit and it decimated the fashion industry in Paris. I was looking for new avenues and was thinking of moving to London. Over the years I’d been away, Mum had tried three designers and they hadn’t worked out. She said, “Why will you give everyone a go except me? Let me interview you.” We both had a very clear agreement. One season, three months, a collection of 20 pieces. If it sold, I stayed. If it didn’t, I left. And it sold. Well, half of it sold really well and half of it sold terribly, but there was enough to show that there was an opportunity.

I’d always avoided the limelight and wanted to avoid a comparison to Mum. We always believed in quality, we always loved beauty, we were always interested in ideas of timelessness, but how we defined our look was so different. My mum was the epitome of the power suit and I was always a romantic. Our natural difference was our strength. Because she really had her signature and when I did my elements in her collection they never competed with hers. They just had a different sensibility, another layer that was offered to the customers.

Soon, we realised it had started branching out into its own world. This was the moment where it needed to stand on its own two feet. People always say to me: “What was it like to break away from your mum?” We didn’t have a fight; it was a natural evolution. The thing Mum taught me in her actions was to be fiercely independent and not be afraid to say what you needed to say. My first presentation, after I separated from Mum, was the most hyper-romantic, otherworldly space; everything was swathes of incredible draping. Mum was primary and black and white. I was tertiary. Mum was fabrics that had a flatness and a modernity to them – mine always had textures. Mum was a very clean and graphic line. I always had this organic, wabi-sabi kind of movement. Being able to have a space where I could amplify and flourish with all of these details was really exciting.

Hitting the 15-year milestone as a business is about seeing the body of work that I’ve created. There’s a part of me that never knew if I would make it to this point. I’m very humble about what it takes to be a creative. Every collection has a really deep narrative and a sense of something I’m trying to evoke. My most recent collection was all about this idea of courage and disrupted beauty. After Mum passed away, I really wanted to embody courage for women. Those are very felt senses and ephemeral ideas, they don’t look like a puffed sleeve or a graphic line. They’re not a mood board that you can just google. They’re me reacting to our universe and what we’re all living through and trying to communicate that as an artist, as a creative, through clothes.

Mum grew up at a time where women had to be men to be in the business arena. They were incredible trailblazers and the clothes that they needed to achieve that were strong and powerful. I think for my generation, empowerment is more about freedom. My clothes have always been about that, in the way they move around you, in the way they will be a little surprising, whether it’s a tailored jacket that’s got a gather through it, or a romantic dress with a little harness piece. Women are so layered, we have so many different parts of us. We are partners, we are friends, we are daughters, we are mothers, we are leaders, we are intuitive feelers.

This article appears in the April issue of Vogue Australia, on sale now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout