Brave Iranian arists are standing up to brutal authoritarian rulers

It would be easier, and much safer, to remain silent, but some leading lights of the Iranian film industry are taking a stand.

She’s a household name in Iran, an actor so widely celebrated she was once mobbed in a Brisbane fashion store when fans recognised her. You might say she is mad to be interviewed over this scratchy VPN link from Tehran, given the very real chance it will land her back in the maw of state security.

And you’d be right, because she is mad. Angry. Incandescent at what has transpired since the death in custody five months ago of Mahsa Amini, the 22-year-old Kurdish woman picked up by the so-called morality police for failing to secure her headscarf.

The actor joined the demonstrations that thronged the streets of the capital, where people chanted “woman, life, freedom” in noisy defiance of the regime. She spoke out in her own right, too, taking to what was left of social media in Iran to denounce the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps for appropriating her celebrity to defend its deeply tarnished reputation.

Now she’s talking to us – veteran Australian TV current affairs and film producer Des Power, a Farsi interpreter who works in the movie industry here, and The Australian – because she wants the world to know the protests are not going away, and neither is she.

“I am never afraid of anything,” she says in rat-a-tat English. “I don’t know what the power is inside me. Maybe it’s when they make force on you … it makes you stronger.”

We’ve agreed not to publish her name as that would be a red rag to the IRGC and the rest of the ayatollahs’ flint-eyed enforcers, but the actor is acutely aware it wouldn’t require much effort by them to identify her.

She insists on telling her story, in potentially giveaway detail, such is her anguish at the plight of her country and its acclaimed film industry – among the theocracy’s few international assets. One by one, friends and colleagues have been dragged off to Tehran’s notorious Evin prison, where she was interrogated and put before a judicial tribunal two months ago.

She used her fame like a shield, daring the mullah and judges on the panel to jail her. That they let her go with a stern warning is testament to both her audacity and courage. Few would have gotten away with it.

But she had to stand up for what was right, to say what needed to be said, because if she didn’t, who would? The actor is no hero. She is a gambler. Anyone who takes on the vicious security apparatus does so at the risk of life, limb and livelihood; this interview is her way of raising the stakes while keeping the bet manageable.

What happens if they come for her again? Let them come, the actor says: “Nobody can bring me down.”

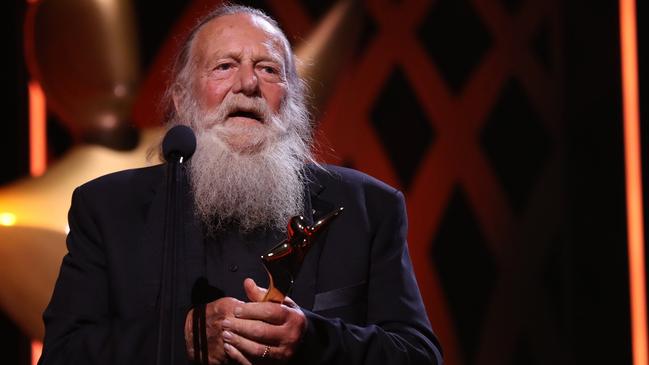

Power, 81, founding chair of the Australia-based Asia Pacific Screen Awards, marvels at her pluck. “She’s their Cate Blanchett,” he says. “We brought her out a few years ago when she slipped away to do some shopping in … the city. Some people recognised her and went crazy. We had trouble keeping them off her and … I thought, ‘wow, this is happening here in Brisbane. What must it be like in Iran?’.”

Power says approaching the international media was entirely her idea and he’s merely the middleman.

“I would feel sick … if there are repercussions,” he admitted, before she came on line. It has taken some organising. The regime slowed the internet in Iran to the point it is mostly unusable. But a Virtual Private Network connection set up outside the country – an encrypted tunnel through cyberspace – can get around the digital blockade, though the service is still patchy.

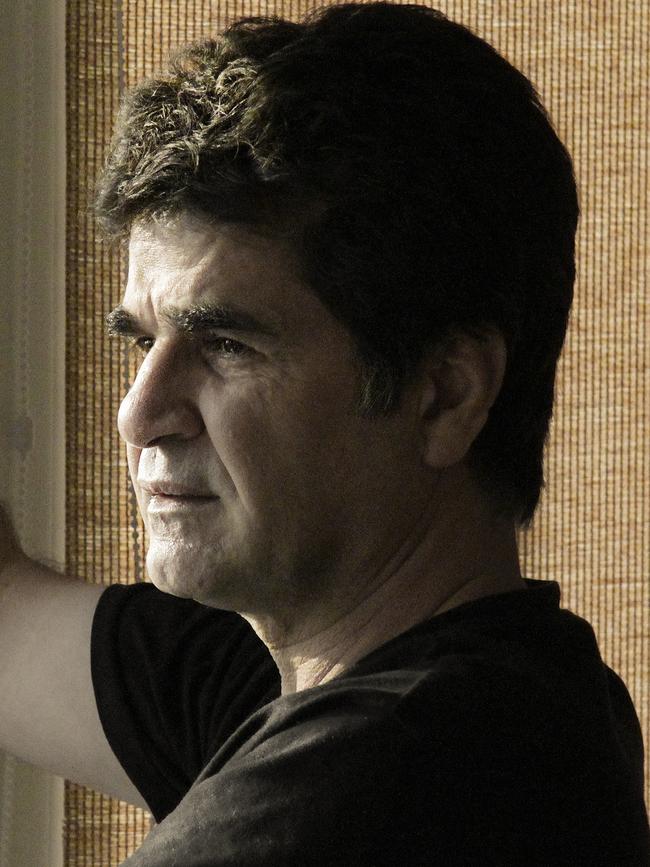

A well-known Iranian filmmaker has also joined the conversation. As we report in the news pages, his warning about the trashing of the country’s proudly independent cinema with state “propaganda” is timely when the international awards season cranked up with last week’s Oscar nominations.

Power listens intently to the translation as the filmmaker details how an operative of the omnipresent IRGC seized control of a movie that is set to go on the festival circuit this year from Berlin to Cannes, Toronto and, of course, capital city dates here. He knows this person well, who is anything but free-thinking.

“They are controlling everything from the roots,” he says of the regime’s takeover. “Now they’re producing and exporting this propaganda and my question to you, to filmmakers and journalists around the world, is how do you identify which film is being produced and supported by the government and which one is not? What is coming out of Iran is not necessarily coming from independent filmmakers.”

After mulling this over, Power says a response will be item No.1 on the agenda at APSA’s first board meeting of the year next month.

Iranian films are the third-most awarded by the Asia Pacific academy, behind only the behemoths of China and India, with 283 featured in the competition since 2007.

“It’s a test of our integrity,” he tells The Australian.

Australian screen legend Jack Thompson, president of the APSA Academy, says the industry worldwide has an obligation to support Iranian cinema. “I understand what it must be like to be the Iranian government or the Iranian people in a world filled with Islamophobia,” he says. “But the fact of the matter is the Koran speaks of the Holy Prophet preaching tolerance. It was his tolerance that led him to forgive his worst enemies.

“And I think it’s something that only goes further to have people wonder what sort of self-denial is involved when those who claim to be keeping the way of Islam … behave in such a totally intolerant way.”

Thompson, 82, has friends in Iran including the actor, a member of the APSA academy. Her initial involvement in the protest movement was low-key: she took to the streets with hijab fixed, keen to not stand out in the crowd.

But that changed when the IRGC used her image, without permission, on a billboard suggesting she backed the crackdown. Within hours of the hoarding going up in a busy square in downtown Tehran she had posted a video denouncing it. And to make sure there was no room for misunderstanding, she called herself the “mother of Mahsa … of all children in our country”.

She was summoned to Evin prison to explain herself: “They asked me, ‘why did you send this video? It’s too much’.” To her relief, she was ordered home while they considered further action.

They interrogated her twice more, the aggression amped up each time. She was waiting to front the judicial tribunal when an admirer in the Basij, the IRGC-run militia that has tentacles reaching into just about every facet of day-to-day life in Iran, whispered to her: beware.

The sentence was already in, the young man said, surreptitiously tapping a folder containing the predetermined court order. “Don’t say anything to make it worse – that’s what they want,” he urged.

Instead, she set her jaw and let rip.

“My face was red, my voice was high when I went in,” the actor remembers. “Being told about that notice made me … how do you say it?” she pauses, querying the interpreter in Farsi. “Yes … like a tiger. It made me like a wild tiger.”

How dare they suggest she was anything but a patriotic Iranian? Her brother had fought in the bloody Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s to protect the revolution, she told them, tears staining her face. Her heart was broken. But if they wanted to punish her, go right ahead. “They know I am loved in this country and … if they touch me, it will not be good for them,” the actor says.

The judges blinked. She was sent on her way with the warning that her dossier remained open and she would not be allowed to work or travel, a slap on the wrists in the circumstances.

Other industry figures have suffered grievously. The filmmaker’s friend, director Mozhgan Ilanlu, was last week sentenced to nearly 10 years’ jail and 74 lashes for protest-related offences including collusion against national security, among the estimated 10,000-plus Iranians arrested since the streets erupted last September. Four people are known to have been executed to date.

Oscar-winning actor Taraneh Alidoosti was taken into custody on December 17, but released a fortnight later in the face of an outcry. As the filmmaker ruefully points out, it helps to be in front of the camera. Take the fate of the world’s most prolific banned director, Jafar Panahi, also an APSA Academy member.

His credits include modern classics such as The Circle, Taxi and the cheekily titled This is Not a Film, made while he was under house arrest.

His imprisonment for six years in July to enforce a pre-existing sentence was salutary, a sign of the storm brewing under hardline President Ebrahim Raisi.

The pressure has been relentless, the filmmaker says. Recently, another colleague committed suicide rather than be put through the wringer. “We cannot survive this without support from the rest of the world,” he says.

The actor says the international community needs to understand the movement galvanised by the killing of Mahsa Amini is like no other to sweep the Islamic Republic, flaring in an outburst of hope only to be crushed by the iron fist of the state.

This time there are no protest leaders to arrest, no outside forces in the form of Israel or the “great Satan” of the US to credibly blame, though that won’t stop the regime from trying. The unrest is organic, deep-rooted and invested in people’s growing awareness that the country’s financial and civic impoverishment is mostly the work of their fundamentalist rulers.

“It’s the first time that a movement like this has happened without any ideological layers to it,” she says. In a way, it’s like improvised acting with a full house of 80 million Iranians warily looking on.

How will it end? The actor can’t say. But she offers this insight: “The people know what they don’t want. They don’t want this government because they don’t want ideological government and they don’t want government failure.

“They will find out as they go through … exactly what they are looking for. The result is going to be very positive.”

Echoing her, the filmmaker says: “The minimum we will get is change. The fact is, we will never go back to what we had. That time is over.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout