Ash Barty and Maha Sinnathamby: Matched by shared love for learning

Ash Barty and property developer Maha Sinnathamby may not appear to have too much in common on the face of it.

World women’s No 1 tennis player Ash Barty and property developer Maha Sinnathamby, whose vision created Barty’s home town of Springfield, Queensland, may not appear to have too much in common on the face of it.

But their paths have aligned over a passion for learning and shared determination.

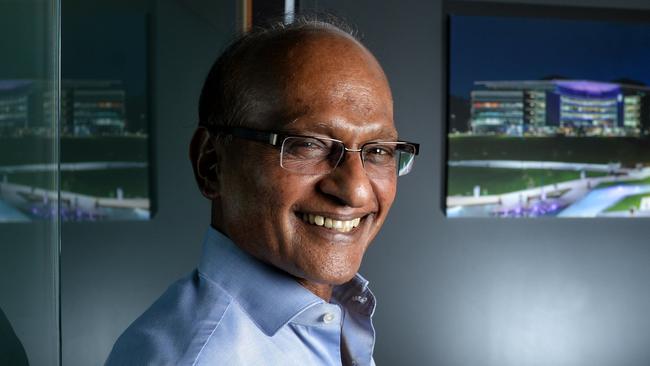

Barty has been made a Springfield ambassador to encourage children to set high education goals. It was an assignment given to her by Sinnathamby, the avuncular Springfield chairman who grew up in a Malaysian village with no electricity and where his family drew their water from a well.

Although he struggled at school and university, Sinnathamby says education opened his eyes to wonderful opportunities.

Springfield’s masterplan has a focus on “lifelong education”, he says. “Education is the only currency you can cash in anywhere is the world … and education is the only currency that cannot be stolen. I drive education hard. I believe in it.

“People coming to live at Springfield value education and I am very happy about that.”

They also come for affordable housing, with house and land packages from $320,000, while larger homes in the dress circle overlooking the golf course go for $1.1m to $1.4m.

Barty and Sinnathamby have a mutual admiration society.

He is proud his new ambassador did not neglect her studies while climbing to the pinnacle in one of the most competitive sports.

“It’s wonderful to have her on our team,” he says. “She is an inspiration.”

Barty grew up in Springfield and was dux in Year 9 at Woodcrest State College.

By Year 12 she was already competing on the international tennis circuit and she completed her homework online.

“Even when I was travelling I was determined to achieve the best academic results I could,” Barty says. “I worked hard and was still getting good grades in Year 12.”

Her sports-mad family valued learning, she says.

“My sisters (Sara, now a midwife, and Ali, a teacher) were both netballers. But netball wasn’t for me so I decided to give tennis a crack,” Barty says.

“We had a lot of friends and I had a very happy childhood. We spent a lot of time outside.

“We would walk to and from school in the years before my training became more professional. We came home and mucked around with footballs, golf clubs, cricket bats and anything we could get our hands on until it got dark and we were called in for dinner.”

She was contemplating a career in sports science or perhaps physiotherapy when tennis called.

“At school I found science and maths my stronger suits,” Barty says. “I have the kind of personality where I love to be able to get a definitive answer.”

She hit it off with Sinnathamby at their first meeting. “Maha is an incredible person. His values and passions align with mine. The push for education at Springfield has been massive.”

Sinnathamby recalls that academe did not always come easy to him. He tells The Australian he felt wretched and lost when his father sent him to Australia to study engineering.

Sydney moved at “a million miles an hour” compared with the village of Rantau in the Seremban district, where he was born on a British-owned rubber plantation.

“I was a failure in just about everything I did. I was not good at school. I went to a St Paul’s Catholic school (at nearby Seremban) and had to repeat a year. I was not a very smart chap.

“I was told to come to Australia by Dad. He said: ‘You are doing civil engineering.’ I didn’t know what it was.”

His new life in Sydney was “a bit of a shock”. “I struggled to matriculate to the University of NSW,” Sinnathamby says. “I didn’t understand what was going on and I failed my first year. I had to repeat and I was not happy about it.

“When I did second year I failed again. I said to myself: ‘You’re a failure all your life.’ I was very upset. I knew my parents were finding it very had to keep me at university and I felt I had let them down. I wrote Dad a letter and said I was sorry.” He thought he would be scolded and ordered to return home. “Dad had to sell one or two cattle to pay my fees,” Sinnathamby says.

He’ll never forget the letter from his father that arrived two weeks later. “He said, ‘Son, just keep going. The darkest night brings the brightest dawn.’ I just cried and cried. The words kept ringing in my ears. From then on I didn’t fail. I just couldn’t.

“I have used Dad’s words all my life. Tomorrow will be better.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout