Apocalypse then and now

The great films of war stretch in every direction and include an astonishing documentary on fighting the Taliban.

In John Milton’s epic, Paradise Lost, which depicts the fall of humankind and a mighty battle in Heaven, the words echo: “War hath determined us.”

The lightning fall of Kabul to the Taliban is a reminder of how war punctuates and determines everything about the world we inhabit.

We went into Afghanistan in the immediate wake of 9/11 when we realised Osama bin Laden effectively had standing al-Qa’ida armies in Afghanistan that could underwrite terrorist acts against the West. An eminent man of the left, John le Carré, justified the incursion into Afghanistan as a necessary, if nasty, exercise.

But there is a long history to remind us Afghanistan justifies its title as the graveyard of empires. bin Laden himself said, looking and sounding a bit like the reincarnation of Saladin, the great Saracen enemy of the Crusaders: “We have destroyed the Russian empire and we will destroy the American one.” He had fought for and backed the Mujahideen, which turned into the Taliban.

Charlie Wilson’s War, that crisp and delicious Mike Nichols comedy drama with Tom Hanks and Philip Seymour Hoffman, shows part of the mad, brilliant dance of how it was done. Yes, and the Mujahideen after they became, as the Taliban, the enemies of the West, were kept at bay by soldiers like the young men in Sebastian Junger’s heartbreakingly beautiful documentary about the war in Afghanistan, Restrepo.

More of this later. It’s clear, though, how much the drama and the glamour of war and, piercing through it, the sorrow and the pity have structured the culture we have and the films we have made.

Homer’s Iliad, the first and the greatest epic of Western culture, is a war story. It begins with the terrible wrath of Achilles and ends with the solemn funeral of Hector, the man he has slaughtered. Troy, with Brad Pitt as Achilles and Peter O’Toole as the Trojan king Priam, was an attempt to retell this story. Just as Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven, with Orlando Bloom and Liam Neeson, was an attempt to capture the tumult and ambivalence of the Crusades and the tension with the Muslim world that has haunted the West.

One of the first films I saw as a child a lifetime ago was King Richard and the Crusaders, the film version of Sir Walter Scott’s The Talisman, in which Rex Harrison plays the great Saracen leader who comes, in disguise, to cure what looks like the mortal illness of Richard the Lionheart. The Jewish stories of war also haunt Hollywood. David weeping for Saul and Jonathan in How are the mighty fallen, and for his dead son in his great cry of “Absalom, my son, my son. would god I had died for thee, O, Absalom, my son”.

The Richard Gere-Bruce Beresford film, King David, doesn’t work but there are a hundred stabs at the story. The war film has a history ancient and modern.

Peter Watkins in the 1960s made grand and terrible documentaries about war — one about a third world war and another, a scarifying brutal depiction of the Battle of Culloden, which ended all Scottish hopes of a nation independent from England. Another great attempt to recreate a terrible conflict in apparent documentary form is Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers.

Versions of the greatest of 19th-century war stories, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, are a mixed bag. Many people would say the sweep and glory, the anguish and the hope of the saga with the backdrop of Napoleon going into Russia is best captured in Sergei Bondarchuk’s 1970 Russian film but the best Pierre is Anthony Hopkins in the 1970s BBC TV version and the Natasha to die for is Audrey Hepburn in King Vidor’s ’50s Hollywood films.

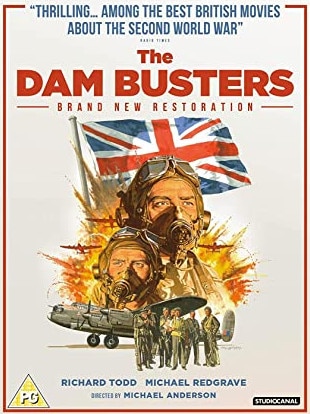

Many baby boomers grew up to the stirring stories of World War II as adventure films. With the grandeur of Churchill’s speeches as a background — he asked Richard Burton to deliver them in a ’60s doco with music by Richard Roger, The Valiant Years — we thrilled to films like Reach For the Sky with Kenneth More as Douglas Bader, the legless airman; and to The Dambusters with Richard Todd and Michael Redgrave about that mob of knights of the sky.

Michael Powell made Ill Met By Moonlight with Dirk Bogarde as Patrick Leigh Fermor, who captured the German general in Crete, and David Lean made Bridge on the River Kwai about the Burma railway with Alec Guinness in one of his greatest roles as a British officer gone mad.

Billy Wilder made Stalag 17 and there was a razzle-dazzle film of The Great Escape with Steve McQueen and Richard Attenborough. In 1962 there was an impressive black-and-white re-enactment of D-Day, The Longest Day, which seems to sport every well known actor in Hollywood and Europe — including Arletty, Jean-Louis Barrault and Curt Jürgens –– speaking in their own languages to spotlight the individual faces and voices of that momentous event.

And, of course, there was more to World War II than the derring-do or its shadow. There was the tremendous power and suffering that Marc Ophuls brought together in The Sorrow and the Pity, which is one of the greatest documentary films ever made.

In the same way many people would say Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List — from the Tom Keneally novel — pales in comparison with the great documentary treatment of the Holocaust in Shoah.

Still, the scene in the Spielberg film with the little Jewish girl and that spot of red in the midst of all the black and white in the Warsaw ghetto is one of the great moments in the career of the man who transformed modern cinema (quite apart from the devastatingly weak and cruel performance of Ralph Fiennes as the concentration camp commandant).

Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan and Terrence Malick’s Thin Red Line, both from 1997, are WWII films by modern masters. The Spielberg has plenty of moments of cornball mush, and the Malick with Nick Nolte as the general who quotes Homer’s description of “rosy-fingered dawn” in the original Greek is a masterpiece but there are moments when the superslick Hollywood wordling takes the breath away.

The sequence where the mother hears the news of her son’s death is one of the great pietas of the modern cinema.

Francis Ford Coppola’s masterpiece, Apocalypse Now (1979), was an extraordinary feat of fusion, perilous at every point, to bring together Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (that story of colonial madness in one of the dark places on the Earth) and Michael Herr’s war narrative.

It’s almost as if Marlon Brando’s potentially overblown performance as the modern reincarnation of Conrad’s monster, Kurtz, symbolises the supreme risk in this epic and tragic depiction of the Vietnam War as an allegory of the hallucination and madness, the capacity for delusion and the sense of horror at once apprehended and embraced, in an “Evil, be thou my good” way central to Coppola’s vision.

Frame by frame, Apocalypse Now has a colour and brilliance and a grandeur as it unfolds the colossal nature of its drama. And, if Brando teeters on the brink of unreality, Martin Sheen is utterly credible as the veteran assassin. The discipline of the performance, despite all the shattered mirrors and blood smearing, is a superb counterpoint to everything outsized in the film — this inevitably includes Robert Duvall as the guy who savours the smell of napalm and who comes surging in, like the embodiment of the barbarism our civilisation encompasses, in his helicopter to the accompaniment of Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries. If the Wagner is a brilliant immersion of high culture into the realm of blood, then the sequence when the world becomes a hallucinogen-accented dreamscape exploits the dark side of hip culture.

Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987), the other great Vietnam masterpiece, is a film so harrowing the mind resists the memory of it. For the longest time we get the endless ritualised cruelty of the marine training camp, the endless chanting and the scatological abuse as Lee Ermey, the drill instructor, turns boys into men and men into killing machines. In the process he tinkers with, then deranges, the mind of the fat boy nicknamed Gomer Pyle, played by Vince D’Onofrio. The comeuppance is one of the most hair-raising things in the history of cinema.

If the mind at first remembers only the merciless chants of the first half of the film, only the memory of the sniper girl at the end stays in the mind. In fact the second half of the film presents Matthew Modine, the fat boy’s friend, nicknamed Joker (because of his John Wayne impersonations) in his travels as a US military journalist at the time of the Tet offensive. There is an elaborate and excruciating sequence with Adam Baldwin, known as Animal Mother, a born killer.

Kubrick is at the height of his powers in capturing both the quiet human kindness of men at war and a sort of adolescent brutishness that makes you want to weep for the heartlessness of the world. The vision that underlies Full Metal Jacket is unflinching and has a power that is all the more terrible for the fact that it also exhibits a bottomless depth of compassion.

Young Vietnamese girls die in agony and pray as they die and beg the appalled American bystander “shoot me!” – a language of annihilation and a prayer for mercy that cuts across all languages. The Kubrick and Coppola films represent the high water mark of what the American war movie can achieve and it’s impossible to imagine them being equalled let alone surpassed.

Recent cinema

However, our recent masquerades of wars have produced fine films. Three Kings (1999) by David O. Russell has as its backdrop the First Gulf War, the one in which Stormin’ Norman Schwarzkopf would effortlessly have toppled Saddam Hussain but George Bush Sr did not want regime change.

Starring George Clooney and Mark Wahlberg, Ice Cube and Spike Jonze, Three Kings is an extraordinary black comedy that involves an attempt to nick some great slabs of gold bullion and includes scenes of torture as well as the spectacle of Wahlberg with a perilously punctured lung.

The whole film has an extraordinary combination of zest and gravity that captures, as if in an allegory, the absurdity and the ghastliness of the military action it depicts and derides. It’s a wonderfully unstable film: you never quite know where you are — with your heart in your mouth or breaking into a laugh.

Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), which brings us to Afghanistan (or at least the lead-up to the conflict’s present moment), is in a very different way also a comic skip around a deadly subject.

It’s all about how a politician, played by Tom Hanks, and a brilliant spook, Philip Seymour Hoffman, contrive to arm the Mujahideen so they can stand up to the Soviets and in fact defeat them. It’s the ’80s, Reagan is president, and Charlie Wilson’s War – the script of which is one of the best things Aaron Sorkin ever wrote – is done with utter sparkle and crispness, and precisely the right balance between big acting and the deft light touch that has always characterised the work of Nichols, the director of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and The Graduate.

The tragic irony that is conveyed without emphasis is the well-made plans of Hanks’ Charlie Wilson and Hoffman’s Gust Avrakotos will defeat the Soviet empire but also lead to the Afghanistan that could be shaped by bin Laden and result in 9/11 and the 20-year stint of America and allies attempting to hold the Taliban at bay.

Charlie Wilson’s War is a comic delight but also a relic from another time. One of the young women who works for Wilson is — surprise — known as Jailbait – and he declares at one point: “You can teach them to type but you can’t teach them to grow tits.”

Amy Adams and Emily Blunt are among his footsoldiers and the late, great Hoffman is a marvellous growling bear smashing the glass of office windows, setting up arrangements in Israel and Egypt as if international affairs of the deadliest kind were a madcap comedy.

This is a jewel of a film born of a brilliant ploy that also had lasting and terribly consequences. It includes a wonderful performance by Julia Roberts as a Texan billionaire and a superb cameo by Ken Stott as a Mossad maven.

The events set in motion by Charlie Wilson’s War have just concluded so alarmingly with the fall of Kabul.

Emmy award-winning, Oscar-nominated documentary Restrepo (2010) presents the intimate face of what it was like for young American soldier boys to defend the impossible cliffs and contours of the empire-destroying country from the Taliban who know it intuitively.

Sebastian Junger extracts revelations of extraordinary intimacy from the men of Second Platoon, Battle Company who spent 15 months in the Korangal Valley in the eastern part of Afghanistan. It is named after one of their dead comrades, PFC Restrepo. This extraordinary piece of filmmaking has a great quality of tenderness and passionate attachment in its depiction of this band of brothers. They are shadowed at every point by the horror of the bloodshed they have witnessed and they have effected. They say their minds will never lose the terrible images they contain nor can they want them to because they are also full of what is what most precious to them.

Restrepo represents the zenith of documentary filmmaking. It is flawless, fierce and absolutely without condescension or any attempt to milk its subject.

At one point the commanding officer, a natural-born leader of men, tells his interlocutors how the Taliban would actually penetrate their bastions and take their equipment before their eyes. “It was so ballsy,” he says, with a look of conviction that is also a look of wonder. The writing was on the valley wall.

There is a stillness and a beauty in Restrepo that is wholly unexpected. We get footage of the rocky terrain by twilight, which has a matchless beauty, and we see in these young boys’ faces the shadows and the flickerings of a world of pain, one you would not wish on anybody.

It’s strange and sad to think that all this tenderness and tragedy was for nothing.

-

Film, TV and the Bart of war

Here we are talking about war movies when the events of the past week in Afghanistan have unfolded in a way that’s as hyperreal,violent and tragically predictable as any film of the genre. Of course, film is an enduring part of our culture precisely because it helps us to make sense of the human experience, including the repetitive tragedy of war.

Sitting in the dark (when we’re permitted to visit the cinema) is a form of group therapy. Streaming, while slumped on the couch at home as we’re more likely to do nowadays, a pose more in the style of Freudian analysis, is as much an opportunity to process civilisation’s cataclysms and loss. Evidently we need a lot of therapy — we keep making war films and a lot of the films are about the same wars.

Sam Mendes was nominated for 10 Oscars for the film 1917, and won three including best picture and best director, some 102 years after the fact. Perhaps Christopher Nolan’s biggest temporal leap yet was the jump back from space to World War II when he followed up his sci-fi Interstellar with the profoundly beautiful, confronting Dunkirk.

By contrast, Casablanca is a World War II movie made in 1941 before they even knew how World War II would turn out.

My late grandfather chased Nazis across Austria (when they weren’t chasing him) as part of a local resistance chapter — the shrapnel lodged in his shin had long since faded to an inky blue by the time I was old enough to ask him about it. He used to love watching war movies — The Dirty Dozen, The Great Escape — and TV scripted comedies too, replete with canned laughter. How he’d chuckle at Hogan’s Heroes and Alan Alda in M*A*S*H. If Hollywood romanticised or made light of the war that claimed his youth, robbed him of every member of his large, loving family and put a bullet wound in his leg, he was all for it. Then again, he wasn’t the type to go in for therapy so I guess it did him good.

Vietnam also took a lot of processing and the ’80s gave us Platoon, Rambo and Born on the Fourth of July. It was an era, mostly, of big, loud films about the theatre of battle.

Quiet, suspenseful Cold War spy thrillers like Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s gripping The Lives of Others require their own compendium.

Then there’s those odd, genre-defying war movies. Buffalo Soldiers, from 2001, might have been set in 1989 but its protagonist, played by Joaquin Phoenix, has a Gen X antihero vibe as he channels boredom into more creatively criminal pursuits in West Berlin.

Charlie Wilson’s War is a heist movie in a war-and-politics wrapper. If you want to brush up on the complex antecedents of the Afghanistan conflict this movie is for you. As Craven notes, it might pretend to be a comedy but the film ends on a note of devastating futility that foreshadows today’s Zeitgeist.

In Australia, we were raised on Peter Weir’s Gallipoli and a series of my school lessons were taken up watching All Quiet on the Western Front and subtitled German language film Europa Europa (was this part of the curriculum or did I have a particularly lazy history teacher?). But as so often happens in pop culture, it’s The Simpsons that teaches it best.

Season one, episode 5, “Bart the General”, features, after much hilarity, this shining epilogue: “Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, contrary to what you’ve just seen, war is neither glamorous or fun. There are no winners, only losers. There are no good wars, with the following exceptions: the American Revolution, World War II and Star Wars trilogy.”

Elizabeth Colman

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout