A beginner’s guide to celebrating Lunar New Year

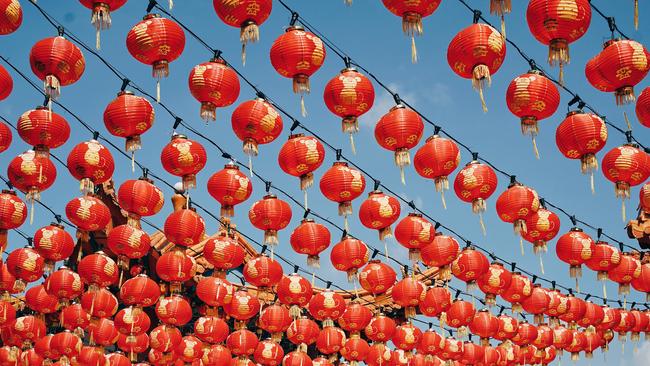

So you’ve been invited to a Lunar New Year’s gathering for the first time? Here’s the rundown on traditions, foods to expect, and superstitions to follow for an auspicious 2021.

Those of us who celebrate Lunar New Year are familiar with its particular brand of chaos — the inordinately large meals, the deafening conversation, the gaggle of distant relatives telling you how much you’ve grown (or need to grow, before force-feeding you at the dinner table). And with the welcoming of a new phase of life comes also the quest for fortune.

A bevy of traditional colours and greetings should be respectively worn and performed — according to your mother’s exact specifications, of course — to ensure an auspicious year ahead. It’s likely that she’ll meet you in the early morning before the festivities commence to make sure you’re presentable (something you never grow out of — for Asian mothers, 40 is the new 9).

Even for the initiated, Lunar New Year is as intimidating as it is exhilarating. So if this year is your first, there are more than a few things you’ll need to know and prepare for. Whether you’ve been invited to a partner’s house or you’re just tagging along with a friend, the etiquette expected of you remains the same. What foods will you be eating? What are the traditional phrases you should use to address everyone accordingly? Are you going to receive a gift, and if so, are you expected to bring one in return?

Here, your most pressing questions are answered so you can breathe a little easier. And don’t worry — if all else fails, just wear red and bring a bag of fresh oranges. They’ll love you, we promise.

What is Lunar New Year?

In Asian countries across the globe, the Lunar New Year marks the beginning of the lunar or lunisolar calendar. Unlike the Gregorian calendar your Apple calendar runs on, which depends on the 365-day solar year, the lunar calendar is based on the monthly cycles of the moon, which varies between 29 and 30 days and amounts to a year of approximately 354 days.

In 2021, the end of the 12 lunations and the beginning of the new year falls on February 12, though it’s normal for celebrations to last much longer, up to two weeks after New Year’s day. In previous years, such celebrations amounted to a pilgrimage, with hundreds of millions of people returning to their families — whether that be in a neighbouring province or another country — in what is widely referred to as “largest annual human migration”. While the shape of Lunar New Year in the post-pandemic age remains unclear, Australians with family in the same country can expect household visits, while those without will be able to enjoy live-streamed music, dancing and religious ceremonies alongside their relatives.

What is the difference between Lunar New Year and Chinese New Year?

Though often used interchangeably, Lunar New Year is not the same as Chinese New Year. Call it the “a square is a rectangle, but a rectangle is not a square” rule. Though Chinese New Year is a Lunar New Year celebration, the beginning of the lunar calendar is celebrated in a myriad of Eastern, Central and Western Asian countries that aren’t just China.

Chinese New Year is arguably the largest of all the Lunar New Year celebrations by the size of its celebrants alone — not only do you have to account for its 1.5 billion citizens, but the millions that constitute the country’s diaspora, including those in Australia. Perhaps the most recognisable feature of Chinese New Year are its 12 zodiac animals. Their particular order during the 12-year cycle originates from a myth of a “great race” between the animals, each competing to be the best-ranked guard of the Emperor. If you’ve been seeing a plethora of bovine imagery about, it’s because 2021 is the year of the ox, the runner-up to the cycle’s (and 2020’s) victor, the cunning rat.

But if you’re not heading to a Chinese New Year event, it’s best to find out the exact name of your particular Lunar New Year gathering. While Koreans celebrate Seollal, Vietnamese communities observe Tết nguyên Đán. Losar is the name of the Lunar New Year for those with Tibetan heritage, while Nyepi and Satu Suro mark the Balinese and Javanese new years respectively.

What foods are traditionally eaten during Lunar New Year?

If there’s anything we ethnic families take seriously, it’s food. Celebrating the new year is synonymous with overfeeding — so goes the age-old joke that not accepting the offer of another serving is the greatest insult you can make to your grandparent. It’s not difficult to understand why the simple act of feasting is viewed as sacred. A Lunar New Year dinner isn’t just eating — it’s the art of folding dough, passed on by your parents and elders, of sharing a meal that you’ve created together in person or in spirit.

The Chinese New Year lunch or dinner will be made up of several key dishes. With generosity being the theme, expect Herculean portions. A whole steamed fish, a pair of roasted chickens or ducks, and an endless array of pork and chive dumplings are staples in the Lunar diet, but beef will not be eaten if a family is of Buddhist faith. If you’re a fan of the chew in mochi or the tapioca pearls in bubble tea, glutinous rice cakes (called nian gao in Mandarin or leen goh in Cantonese) and sweet dumplings filled with red bean, peanut or sesame paste (called tangyuan in Mandarin or tong yun in Cantonese) will be right up your alley. Sliced oranges are sure to bring the night to a close, so do yourself a favour and bring along a bag. It’s a one-way ticket to instant prosperity — and ingratiation.

Attendees at a Vietnamese Tết feast will encounter the parcel of deliciousness that is banh chung or banh tết (from Northern and Southern Vietnam respectively), a square of glutinous rice filled with pork and mung beans, wrapped up and boiled in bamboo leaves that colour the rice green. Candied fruits (called mut) are accompanied by cups of tea, while melon seeds, pickled scallion and braised pork with eggs will also make an appearance. In Korea, a rice cake soup called tteokguk, kimchi dumplings and yaksik — sweetened rice mixed in with dried fruit and nuts — are traditionally eaten on New Year’s day, while the Ryukuan New Year in Japan is celebrated with chestnut and sweet potatoes, black beans, and egg and fish pancakes called datemaki.

Though you are by no means expected to eat until you burst, it’s considered polite to try a little bit of everything. Each dish is viewed as containing its own piece of luck, and the act of eating is thought of as receiving the fortune you’ll need for the year ahead. Oh, and practice your chopstick skills — skewering your food is seen as improper.

What traditional greetings should I learn for Lunar New Year?

We empathise — the intonations for Asian languages are rough, and not the kindest to foreign tongues. But practice makes perfect, and you’ll definitely be lauded for trying some well-wishes to share throughout the party.

The Cantonese “gong hey fat choi” or the Mandarin “gong xi fa cai”, which translates to a wish for the recipient’s happiness or good fortune, is the most commonly spoken phrase during Chinese New Year. “Sun nin fai lok” (Cantonese) or “xin nian kwai le” (Mandarin) meaning “happy new year” is also a must-say. In Cantonese, “fai gou jeung dai” (grow taller and bigger quickly) is usually said to children, while “lung ma jing sun” is professed to older relatives, wishing them the energy and vigour of a horse.

In Vietnamese, a happy new year greeting, “chúc mừng năm mới”, is sometimes substituted with wishes for the new spring, “cung chúc tân xuân”. “Cung hỉ phát tà” expresses a desire for prosperity, while “sống lâu trăm tuổi” is a hope expressed to a loved elder for a 100-year-long life. Korean families will appreciate it if you wish them a happy new year with “saehae bok mani badeuseyo”, while those attending a Japanese Lunar New Year event should try their hand at “akemashite omedetō gozaimasu”.

While the Cantonese sayings are pronounced exactly as they’re written, the Mandarin, Vietnamese, Korean and Japanese phrases are a bit trickier. Here’s a phonetic breakdown of the key phrases we’ve mentioned.

Repeat after us...

Gong xi fa cai = gong zee fah tsai

Xin nian kwai le = sin nyan k-why luh

Chúc mừng năm mới = chook moong nahm moy

Sống lâu trăm tuổi = song laow tscham two-oy

Saehae bok mani badeuseyo = say-hay bog manh-i bah-duh say-oh

Akemashite omedetō gozaimasu = ah-keh mashi-teh oh-mehdetoh go-tsa-ee-mahsoo

Do I need to bring anything to a Lunar New Year party?

Lunar New Year is a day of exorbitant giving and receiving, but if you’re a guest at a partner or a friend’s gathering, don’t worry about the giving part too much (except for the oranges, of course). For Chinese New Year especially, there are too many taboos you might break by choosing the wrong gift. Pears, umbrellas, mirrors and anything black or white are associated with misfortune. Also relegate your bouquet of roses to Valentine’s Day — cut flowers, especially chrysanthemums, represent the literal opposite of blooming romance, and are only presented at funerals.

The most common gift given out on Lunar New Year is the red packet, which contains “lucky money” — these are usually given out to the children and young adults of the family, and contain anywhere between 20 to 100 dollars. If you are given a red packet, do not return it or insist that you can’t accept it — there’s a risk you’ll be perceived as insensitive or ungrateful.

What should I wear during Lunar New Year?

Although it’s not prohibited, don’t turn up in traditional clothes such as cheongsams unless you’ve been specifically asked or given them it could come across as costumey. Red is a foolproof colour for whatever country’s Lunar New Year dinner you’re going to, and if you’re not a fan of crimson, try to wear brightly-coloured clothes such as yellow, vibrant greens or blues. Do not wear black or white, which are shades strictly associated with funeral rites and mourning.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout