Oh dear. It already has turned into Xi’s annus horribilis, smitten by triple trouble: pandemic, economic and geopolitical.

He pronounced proudly during his Tiananmen Square speech for the Chinese Communist Party’s centenary on July 1 last year: “In today’s world, if you want to say which political party, which country and which nation can be confident, then the Communist Party of China, the People’s Republic of China and the Chinese nation have the most reason to be confident!”

All he needed was stability to frame the dominant event in China in 2022: the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th five-yearly national congress, due in early November. Its core preordained outcomes comprise a further five-year term for Xi as party general secretary, and unanimous backing for the ambitious new platform for China’s future that Xi will deliver in his three-hour keynote speech.

Xi, enforcing stability at home while anticipating it abroad, envisaged that these targets were well within reach, elevating him above his predecessors in China’s communist dynasty – except Mao Zedong, whose legacy he might then look on as an equal.

Only four months ago, the politburo stated it would “place the word ‘stability’ as the top priority” for 2022. The word appeared 25 times in the economic report for the politburo’s meeting in December last year.

Xi – who has not left China for more than two years – gave his usual keynote address, virtually, to the World Economic Forum in Davos in January. “We need to move forward by following the logic of historical progress,” he said, adding: “The practices of hegemony and bullying run counter to the tide of history” – news, now, to Ukraine. Today, however:

● The country’s finance centre and manufacturing hub, Shanghai, is simmering with resistance to the government’s unyielding “zero Covid” policy that is confining most of its 24 million inhabitants in their homes as the Omicron variant strikes, many families anxious about where to find food, and with cases well exceeding those in Wuhan two years ago.

● China’s vaunted supply chains are being disrupted severely as the cities accounting for half of its economic production are locked down, also risking the present scattered examples of food shortages becoming more widespread, exacerbating the effect of a poor grain harvest.

● The economy is slowing rapidly, the first quarter’s growth rate of 4.8 per cent making the annual official target of about 5.5 per cent already appear unrealistic.

● Beijing’s refusal to criticise Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is underlining its alienation from liberal democracies and highlighting the possible vulnerability to secondary sanctions of some of its own companies that continue to trade with Russia.

● Taiwan is learning rapidly from Ukraine’s resistance how to protect itself more plausibly from potential invasion from China.

After the initial Covid setbacks in Wuhan two years ago, when the party was widely blamed for responding too slowly, for keeping information about the pandemic secret and for punishing whistleblowers, Xi was recast as the People’s Leader winning the People’s War against the pathogen.

He boasted in honouring Winter Olympics workers: “As some foreign athletes have said, if there was a gold medal for responding to the pandemic, then China deserves it.”

The core policy is zero Covid. Cities are closed down with a single case. Officials are blamed for any cases within their jurisdictions. Thus reporting, especially of Covid-related deaths, has become highly politicised and fraught.

The inevitable entry this year of the more contagious but less deadly Omicron variant is acutely testing China’s zero Covid strategy. The site where a dozen years ago a dynamic World Expo was staged in Shanghai’s ultra-modern Pudong sector has become a huge enforced quarantine encampment with minimal facilities and bright lights blazing 24/7. The locale that pointed towards a progressive Chinese future now symbolises instead China’s appearing to turn its face from the advanced, cosmopolitan world.

Grim stories have emerged from Shanghai of tiny children separated from parents, of people with serious non-Covid illnesses dying after being refused access to hospitals, of pet dogs beaten to death by health workers, of “big whites” – Covid enforcers dressed in white hazmat suits – attacked by residents who resent their orders and now view them as sinister.

Moderate levels of vaccination, with Chinese vaccines less effective than mRNA shots, not yet approved for use in China, and consequent modest levels of herd immunity, are exacerbating the dilemma. Many have come to fear the zero Covid measures more than catching Covid.

National Health Commission director Ma Xiaowei, in party theoretical journal Qiushi, recently praised Xi’s “personal” Covid management, for “providing important guidance at every critical moment”. Thus zero Covid is set to stay, at least until the party congress.

Ten days ago Xi told officials: “Persistence is victory. It is necessary to overcome paralysing thoughts, war weariness … and slack mentality” – and warned they would be “severely punished” if they let the outbreak get out of control. Thus, if in doubt, a city will be locked down and the economic impact will persist – along with the sometimes extreme social costs.

For example, the Tesla plant in Shanghai was shut for three weeks but has just reopened under a “closed-loop” regime where the workers must live entirely within the factory, having been provided with sleeping bags and mattresses.

Premier Li Keqiang acknowledged a week ago the severity of China’s latest challenges: “The global situation is complicated and evolving, and pandemic outbreaks have been reported at home. Some emergency factors have already surpassed expectations.”

Despite some pick-up in economic data in January and February after a slump to just 4 per cent growth in the final 2021 quarter, the figures deteriorated across the board last month and are expected to worsen again this month.

Thus job support – with unemployment rising to 6 per cent across 31 major cities – and price controls were needed, Li said, to help keep the economy “within an appropriate range”. The central bank responded by relaxing modestly the ratio of deposits it required commercial banks to hold, encouraging them to lend more.

Local governments are being licensed to issue more bonds to stimulate infrastructure spending in the anxious months before the party congress – though implementation may prove tricky as lockdowns keep biting.

World Bank President David Malpass said last week it was “probably good for everyone” that countries reduced their dependence on China by diversifying their supply chains.

But the sluggishness of the economy should not be attributed solely to the severity of zero Covid or to the pandemic itself. It is also driven by other government policies. Andrew Batson, the China research director of Gavekal Dragonomics, said recently: “For decades it was a truism that what China cared about most was getting richer.” But Xi, at the start of his second term as general secretary in 2017, announced his priority was to deliver “national rejuvenation”, a project more explicitly political than economic.

A year ago, Batson said, Xi – emboldened by the apparent success of the 2020 Covid lockdowns – embarked on full-fledged implementation of his vision of a restructured economy and society, cracking down on financial risk and the real estate sector, closing down many private education providers, and unleashing the full gamut of government and party agencies to heavily regulate China’s most globally successful sector – Big Tech.

Internet companies’ stock prices collapsed and major property developers suffered huge bond defaults. Real estate sales fell 29 per cent last month from March last year, and groundbreaking tech sector founders, including Alibaba’s Jack Ma, TikTok’s Zhang Yiming and JD.com’s Richard Liu, have started to step down. Last month social media giant Tencent reported its slowest sales growth.

Singapore-based business analyst IMA Asia anticipates that this year India, Malaysia and Taiwan will exceed China’s growth, while Vietnam, Indonesia and Australia will be in the same growth ballpark as China.

As the economy has slowed rapidly, Xi’s slogans “dual circulation”, meaning a focus on domestic economic circularity while maintaining less prioritised external connections, and “common prosperity”, focusing on redistribution rather than wealth creation – ubiquitous last year – have been downplayed.

Common prosperity gained only a single mention in Li’s report to the annual parliamentary session last month, when he warned of “the triple pressures of shrinking demand, disrupted supply and weakening expectations”.

But recent efforts to restore battered sectors, Batson believes, amount to “a change in short term tactics, not long-term strategy”.

Lowy Institute international economics program director Roland Rajah and researcher Alyssa Leng criticise China analysts who “essentially extrapolate the trend” beyond the short to medium term. They conclude in a new Lowy paper: “China will likely experience a substantial long-term growth slowdown owing to demographic decline, the limits of capital-intensive growth, and a gradual deceleration in productivity growth.”

They say: “Even with continued broadbased policy success, our baseline projections suggest annual economic growth will slow to about 3 per cent by 2030 and 2 per cent by 2040.”

China will thus eventually overtake the US as the world’s largest economy but remain “far less prosperous and productive per person even by mid-century”.

The third blow disrupting Xi’s hoped-for year of stability and ultimate glory is geopolitical: the Ukraine war. As with the pandemic and economic challenges, central government policy decisions in this area too have exacerbated the negative effects for China.

Only a few weeks ago, in their rousing 5000-word “no limits” joint statement, Xi and Vladimir Putin, whom he has called “my best, most intimate friend”, mapped out intensified co-operation, celebrated “redistribution of power in the world” and pledged – astonishingly, given the horrific events since then – “to counter interference by outside forces in the internal affairs of sovereign countries under any pretext”.

Their Covid confinement may have encouraged both Xi and Putin, already isolated by being surrounded by yes-men, as Kevin Rudd has pointed out, to over-egg their ambitions because of their increased solitude.

The courage of the military and civilians of Ukraine, the West’s cohesive response and the economic waves washing through the world, including energy shortages and inflation, all comprise further bad news for Beijing.

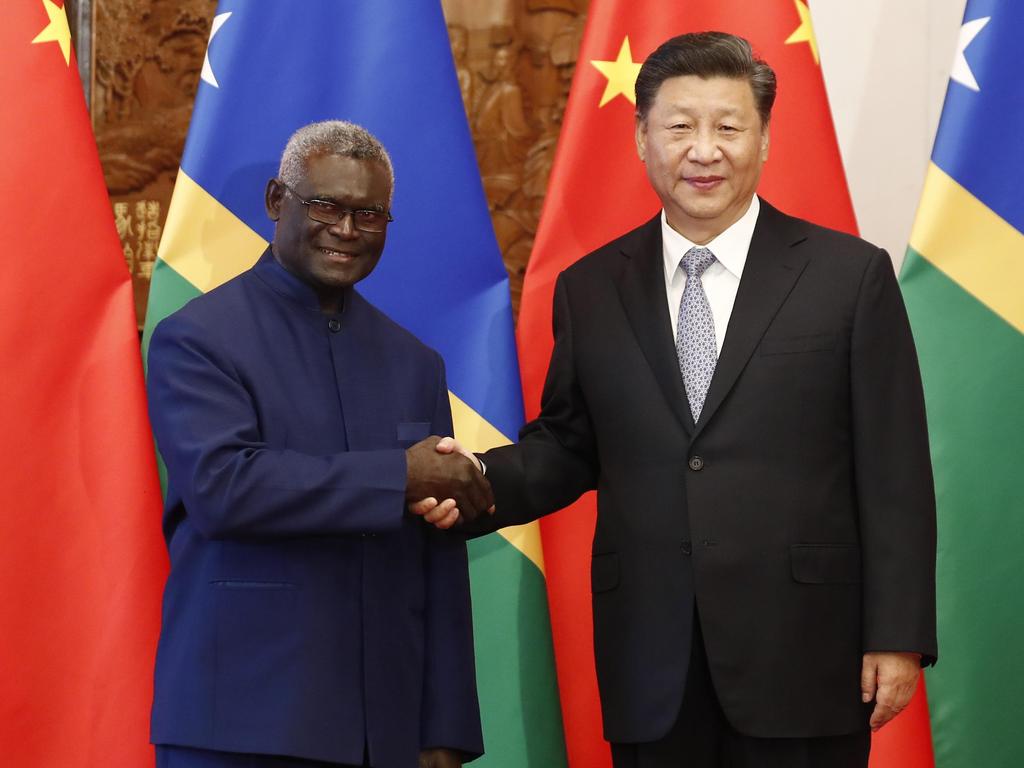

China is not “standing in the middle”, as some claim. Foreign Minister Wang Yi has stressed that the China-Russia relationship remains “rock solid”. Misplaced hopes of Xi acting as a peace broker with Putin have evaporated.

On Thursday, Xi championed in a video speech to China’s annual Boao Forum a new world order based on a “global security initiative” incorporating Beijing’s formulation to justify Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – the “legitimate security concerns of all countries”, in this case to counter the spread of liberal democracies. Xi aligns in this campaign with Putin, appropriating the latter’s signature “principle of indivisible security”.

But the democratic pushback keeps growing in strength. Among China’s important neighbours, a new Japanese Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida, and new South Korean President, Yoon Sook-yeol, have emerged who are both staunch supporters of their US alliances and are concerned about China’s growing ambitions.

Unlike the old Soviet Union, China is economically enmeshed internationally and is thus vulnerable. Beijing rejects the required relinquishing of political controls to enable China’s currency to become convertible on the capital account. So the US dollar remains the global reserve currency and China, like Russia, must conduct international transactions on the SWIFT network from which Russia now has been dumped.

And residual realists in the Beijing political inner circle will view the withdrawal of international corporations such as McDonald’s, Nestle, Uniqlo and Unilever from Russia or their suspension of trading there as a troubling precedent.

In June last year China legislated sanction-busting measures to punish by black-listing, seizing assets and other measures individuals or firms that respond to “discriminatory measures” against the Chinese Communist Party, government or individuals.

Thus if the geopolitical climate degenerates gravely, every company and executive operating in China may have to decide whether to abide by sanctions imposed by the US or other entities, or by China’s countermeasures. It’s all adding a further layer of risk to doing business in China.

And eminent Chinese economist Yu Yongding has warned that “if China incurs sanctions similar to those against Russia, its overseas assets face the danger of zeroing”. He cautioned also about the danger to China of debt traps in Belt and Road investments – traps for beleaguered Chinese banks as well as for impecunious borrowers.

The formerly close relationship between China and Ukraine adds to Beijing’s geopolitical discomfort. Xi personally signed the PRC-Ukraine Treaty of Friendship and Co-operation in December 2013 that included Beijing’s vow to support Ukraine’s “sovereignty, security and territorial integrity”.

Xi hopes to maintain both political alignment with Russia and integration with the broader global economy, believing most countries will prioritise their economic relationships with China over political or security disputes – even while Xi himself always places politics first.

This annus horribilis is bad for China as well as for Xi. Community frustration and, in places, anger is growing – though it is fragmented and Xi has destroyed figures or factions around which it might coalesce.

But if Xi’s friend Putin is dislodged, if party legitimacy starts to seem at stake, if the leader’s mandate of heaven appears to be ebbing away, drums may begin to be heard beating for change of sorts for China.

Rowan Callick is an Industry Fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

This was going to be the time of Xi Jinping’s crowning triumphs. The auspicious Tiger Year of 2022 was promising to become the Year of Xi’s Glorious Re-Coronation as Paramount Leader, the Year of Chinese Supremacy Over Western Covid Incompetence, the Year of the Resurgent Chinese Economy, and the Year of New Era Interdependence for the Twin World Powers of Russia and China.