Worried about the Indigenous voice to parliament? Wait until you see the treaty

A Yes vote in the referendum is not the end of the process but rather the starting gun to a long and divisive treaty negotiation.

Australians will discover that if they vote Yes, the constitutionally entrenched Indigenous voice is not the conclusion of the intended makeover of our national governance arrangements. It is but the first step. While the voice is a major change to our Constitution, it is a mere enabler for activists’ overriding objective of a treaty with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

What few voters understand is that while the voice provides the necessary negotiating platform and leverage for activists to achieve the desired treaty, the new constitutionally enshrined race-based body is only secondary to the treaty. That is because the voice does not in itself give ATSI people the two things activists really want: namely, sovereignty and a form of self-government, and reparations. Only a treaty can do that. That’s why voters should realise that a Yes vote will likely guarantee many more years of agitation and division until, and perhaps even after, a treaty is achieved.

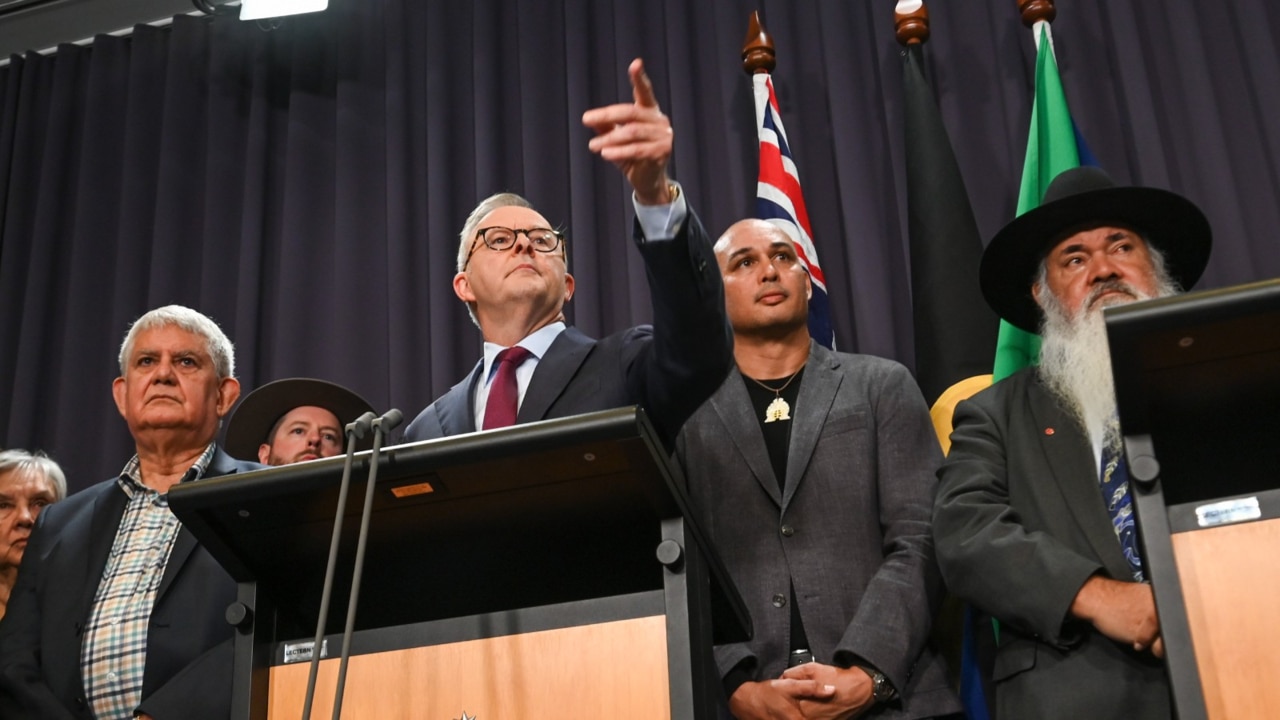

Anthony Albanese can be expected to do his usual Chicken Little routine, accusing those who are curious about what comes next as fearmongerers. The shame is that the Prime Minister is intent on concealing what comes next.

The next stages are obvious, not because I say so, but because this is what the Uluru Statement from the Heart, and the academic writings that have driven the treaty movement, say.

The Uluru statement is the starting point. It calls for a “First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution” but acknowledges this is not the culmination of their ambition. As the statement says, “Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda … we seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between government and First Nations and truth-telling about our history”.

Given Albanese said in his election victory speech “on behalf of the Australian Labor Party, I commit to the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full”, Australians need to understand clearly what this treaty – the end point of the Uluru statement – means.

The definitive description of what the treaty means can be found in the 2020 edition of the book Treaty by George Williams and Harry Hobbs. Williams is a prominent legal academic from the University of NSW and was a member of the constitutional expert group that advised the government on the drafting of the proposed constitutional amendment. Hobbs is also a Sydney legal academic.

Sovereignty, the first aim of a treaty, raises fundamental questions about how the country will be governed in the future. As the Uluru statement shows, those pushing for treaty, including Williams, Hobbs and other members of the academic legal movement, do not accept the traditional view that we have in Australia a single sovereign entity in whom exclusive legal and political power is vested.

The High Court in Coe v Commonwealth in 1993 made clear that the Mabo decision does not support “the notion that sovereignty adverse to the Crown resides in the Aboriginal people of Australia. The decision is equally at odds with the notion that there resides in the Aboriginal people a limited kind of sovereignty.”

Williams’ and Hobbs’ response to this is to question Australia’s very legitimacy, saying the “reality” requires us to recognise that “the Australian nation-state has a legitimacy problem that remains unresolved”.

With that as their starting premise, it is not surprising that Williams and Hobbs call for a treaty which meets three conditions: “First, it must recognise Indigenous peoples as a polity, distinct from other citizens of the state on the basis of their status as prior self-governing communities. Second, the agreement must be reached by a fair negotiating process conducted in good faith and in a manner respectful of each participant’s standing as a polity. Third, the agreement must settle each party’s claims … (t)his must include the state recognising or establishing some form of decision making and control for the Indigenous people that amounts to a form of self-government.”

The first element requires us to accept that Australia is not one indivisible nation. It has two polities. The first and third elements call for some form of self-government by Aboriginal people.

While Williams and Hobbs are not prescriptive about what form that takes, they quote the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which says Indigenous peoples have the “right to autonomy or self-government” in relation to their “internal and local affairs”.

As an example of what this might mean, Williams and Hobbs quote Canada’s treaty with the Nisga’a people which recognises the Nisga’a right “to exercise self-government over a range of local and internal affairs, including lands, language, culture, education, health, child protection, traditional healing practices, fisheries, wildlife, forestry, environmental protection and policing.”

There is a proviso, that says in the case of an inconsistency, federal or provincial laws prevail. But even with that, a similar treaty in this country would carve out for one group, based on race, a separate set of laws and policies that other groups do not have open to them. In other words, a treaty would divide Australia, not unify it.

What about reparations? In the foreword to Treaty, Mick Dodson says there must be a recognition “that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders have been injured and harmed through the colonisation process, and just recompense is owed”. Williams and Hobbs have a stab at estimating the size of possible financial settlements by referring first to the precedent of the settlement between Western Australia and the Noongar people in 2016 that gave the Noongar a package valued at $1.3bn consisting of “a sizeable land base, non-exclusive rights to resources over an extended area, a large and sustained financial contribution from the state government, and enhanced cultural heritage protection”.

More expensively, they point to the Timber Creek decision in 2019 in which “the Ngaliwurru and Nungali peoples were awarded about $2.53m for 53 acts carried out on 1.27sq km of native title land. As there are about 2.8 million sq km of native title holdings across the country, the potential total amount of liabilities will likely be in the billions of dollars.”

If a treaty, with its promise of sovereignty and self-government, accompanied by billions of dollars of reparations, is the main game, how does the voice help? The voice is the enabler because it delivers massive leverage when it comes to negotiating the treaty.

Yes campaigners have tried to distance themselves from Thomas Mayo, a prominent backer of the voice body, who said, in 2021, that the power of the voice was its ability to “punish politicians that ignore our advice” on legislation and funding.

But Mayo’s honesty is refreshing. “We need the power of the Constitution behind us so we can organise like we’ve never organised before,” he said that same year.

“We are sick of governments telling us no; we are sick of governments not listening to our voice. We are going to use the rule book of the nation to force them.”

Even if the government has no legal duty to consult the voice in the absence of a request to do so, the voice can easily create a duty to consult by the simple device of asking to make representations.

The voice need only send a letter on the first day of its existence to every government department, agency or body saying it wishes to make representations on all “matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”. asking for advance notice of all such matters and for the time and resources to consider such matters properly, and thereafter each such government entity will have a constitutional duty to comply.

Once those entities of executive government have complied with that request, the voice will have all the rights conferred by administrative law to ensure their representations are allowed due process and that decisions about them comply with the rigorous standards of administrative law. Failure to do so means any decision that is the subject of a representation may be stopped until litigation about compliance with constitutional and administrative law is completed. In short, the voice can, if it wishes, work to bring the processes of government to a grinding halt.

The activists who dictated the maximalist drafting of the proposed amendment – especially its reference to “executive government” – know this. Those few words will leave the government at the mercy of the voice when it comes to negotiating a treaty.

The lesson is this. A Yes vote in the referendum is not the end of the process but rather the starting gun to a long and divisive treaty negotiation where the voice has the whip hand. This will likely lead to separatism and bitterness, not reconciliation.

So if you are worried about the voice, wait until you see the treaty.