Workers are the casualties in CFMEU’s uncivil civil war

The ousted head of the CFMEU laments the demise of a once-powerful labour leviathan.

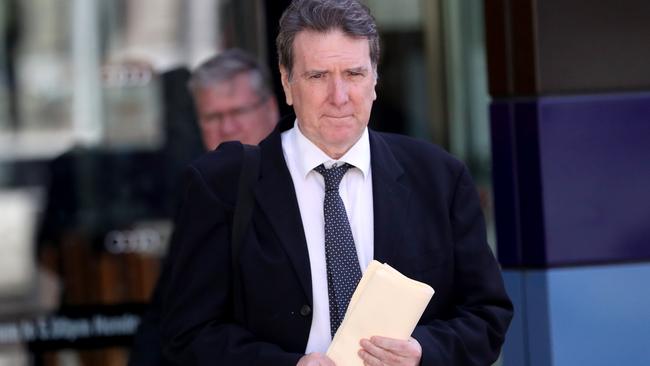

Michael O’Connor is on the phone — and, unusually, on the record — speaking candidly about the civil war that has torn apart the CFMEU and cost him his job as head of Australia’s most notorious union.

“It can be soul-destroying watching what was once a unified union split,” O’Connor tells Inquirer. “Because what you know is the majority of people you are dealing with, no matter what side of the argument you are on, are committed to trying to do the right thing by their members, and the right thing by workers.

“And somehow that doesn’t translate into a positive thing; it ends up being negative, it ends up being where we’re at: a seriously divided, dysfunctional union. That’s pretty soul-destroying.”

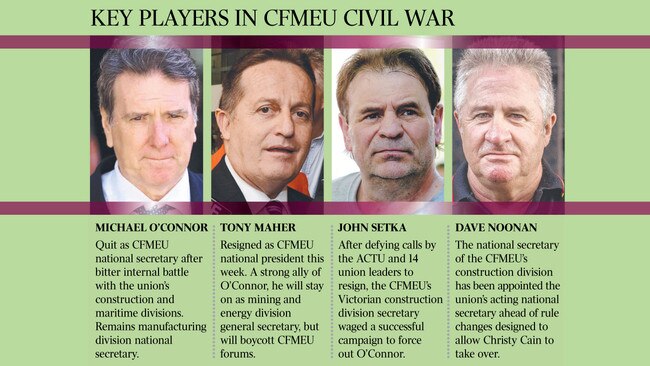

O’Connor resigned this month as national secretary of the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union after a majority of officials sided with the union’s Victorian construction division secretary, John Setka, to force O’Connor out.

Union leaders observe darkly that Setka’s relentless campaign has achieved what the federal Coalition and hostile employers tried and failed to do for years: the weakening of the power and influence of the CFMEU, both politically and industrially.

When the maritime and construction unions amalgamated in 2018, the country’s two most militant unions became a 144,000-member super union, with combined assets of $310m and annual revenue of $146m.

Employers ripped into the Turnbull government for failing to torpedo the merger, warning that key supply chains would be destabilised “from pit to port”.

Less than three years later, the union has imploded. O’Connor will stay on as the national secretary of the union’s manufacturing division but it will boycott union meetings involving construction and maritime division officials.

Tony Maher, an O’Connor ally and general secretary of the mining and energy division, quit this week as CFMEU national president, accusing the construction division of bullying, and declaring the union “impossibly divided and dysfunctional with no repair in sight”.

Claiming the construction division had torn down O’Connor’s leadership, Maher says the mining and energy division will operate as an independent federal union, withdrawing its involvement in CFMEU forums and activities.

“My view, shared by our central council, is that there is no benefit in continuing in a national leadership role in circumstances where our biggest division (construction) has decided to simply use its numbers to bully and steamroll smaller divisions,” he says.

The departure of O’Connor and Maher from the CFMEU’s national leadership is a blow to the union’s ability to influence policy outcomes inside the ACTU and the ALP.

Despite the union being characterised by conservative opponents as a reckless cowboy outfit, O’Connor and Maher are respected across the labour movement — and by many employers — as politically astute, strategic thinkers, which is not a quality that Labor MPs and union leaders readily credit to Setka.

Union officials attribute much of the CFMEU’s political influence nationally to O’Connor’s skilled advocacy, including his ability to disarm sceptics in the face of questionable conduct by construction officials.

O’Connor, the brother of Labor frontbencher Brendan O’Connor, acknowledges that the union’s ability to influence ACTU and ALP policy has been “seriously diminished”.

“I think each of the divisions has the capacity to deliver for their members and represent their members really well, but what we don’t have is the capacity to work across the union as a whole and extract an industrial dividend which would help our members and help their families and help their communities,” he says. “That’s not able to be realised at the moment, and I can’t see it being realised in the near future. All that potential I think has vanished. It has evaporated.”

Supporters of O’Connor maintain the campaign against him was essentially “revenge” by Setka, who was angered that O’Connor did not publicly support him after Setka was charged with harassing his wife, and the Labor Party moved to expel him.

“Everything we have built up through the amalgamation has been destroyed, it’s all f..ked,” one official recently told Inquirer. “All because Michael didn’t support John over his domestic violence conviction. That’s what it boils down to. You only need to state that to see how absurd it is.”

Contacted by Inquirer this week, Setka declined to comment, while O’Connor says: “I am not going to comment on the issue of John and myself. I am not going to go there. We had a constructive relationship for quite a while, and now we don’t have a relationship.”

Asked about the conduct of the construction division, which combined with the maritime division to pass no-confidence motions in his leadership at national executive, O’Connor replies: “Obviously I disagreed with the way they behaved. Each of us has to take responsibility for our own actions. Some people were constructive in trying to resolve issues, some people were not.”

Does he take any responsibility? “I always reflect on my behaviour, whether I did the right thing or the wrong thing. I think some people never do.”

But he does have regrets. “I think you always regret it if relations break down and the union can’t realise its full potential,” O’Connor says.

Indicative of the dysfunction is that the union’s rival camps are in dispute about whether a number of officials are eligible, under union rules, to be national executive members.

Maher says officials Jade Ingham and Nigel Davies are not eligible because they had failed, as required by union rules, to nominate for positions as members of the construction division’s national executive committee.

O’Connor’s supporters have also raised questions about whether Dave Noonan, the construction division national secretary, is eligible, claiming he did not fill out a nomination form for the position as assistant national secretary.

Noonan had temporarily succeeded O’Connor as national secretary ahead of attempts to install maritime union official Christy Cain, a strong ally of Setka. Union rules allow only division heads to become national secretary, meaning they have to be changed to ensure Cain’s elevation. Both Cain and Noonan declined to comment.

The public claims of dysfunctionality have now caught the attention of the government union regulator, the Registered Organisations Commission.

“The ROC is monitoring the developments which are being publicly reported concerning the functioning of the CFMEU,” an ROC spokeswoman tells Inquirer. “The ROC has written to the executive of the CFMEU to seek clarification about the matters being reported.”

Citing the public comments made by officials, the ROC has questioned the union about whether officials are capable of performing their duties, given the cited dysfunctionality.

Opponents of Setka have also raised concerns about the conduct of imminent union elections in the wake of the poaching of hundreds of manufacturing division members by Setka’s organisers in Victoria.

A Federal Court full bench recently ordered Setka to stop the poaching after a successful appeal by O’Connor, but orders are yet to be made about the return of the members.

O’Connor says the future of the union is uncertain. “As far as I’m concerned, I am concentrating on the future of the manufacturing division and its members, their families and the communities that rely on their jobs, so I cannot see a union-wide campaign or union-wide action occurring in the future,” he says.

“I think each division, in the main, will go its own way. The potential we had when we pooled all our resources together is not there anymore.

“Each division will produce good industry policies separately. They will achieve some good results but it won’t be as good as when we all worked together. The people who will suffer for that will be our members and their families so it’s a real disappointment.”

In May, the federal government shelved its union-restricting Ensuring Integrity Bill ahead of months of discussions with unions and employers about proposed industrial relations changes. Does O’Connor believe the union is now vulnerable to a renewed attack by the Coalition?

“I think the government will think we are more vulnerable, and if the government thinks we are more vulnerable it might encourage them to step up their efforts,” he says.

“If you are weaker because you are not united, then by definition you are more vulnerable. But even divided I think each of the divisions can carry out a bit of activity. They are still pretty effective in their own right.”

That said, O’Connor admits that the once strong union is in a bad way. “As far as the splits and the dysfunctionality and the bitterness, I think it’s the worst I’ve seen,” he says. “There have been pretty dark days inside the CFMEU, but I think this is the worst I have seen it.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout