Wong’s hostility to Israel – like Whitlam’s – betrays all Hawke held dear

Penny Wong praises Bob Hawke’s memory – but her words bury him, along with the good he did.

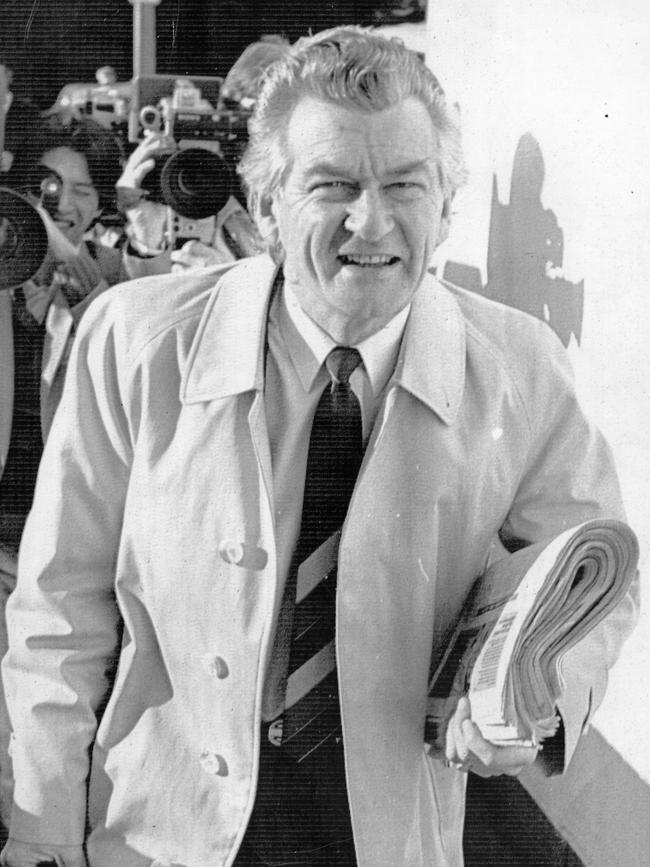

It is a rare if somewhat paradoxical treat to have Foreign Minister Penny Wong delivering an oration in honour of Bob Hawke this week. Hawke was undoubtedly the most passionately zealous friend of Israel of any ALP leader – and arguably of any prime minister this country has had. In the 1970s he incurred vicious opposition from the ALP’s Socialist Left as well as death threats towards himself and his family because of his unswerving advocacy of Israel’s rights.

Wong praises Hawke’s memory but her words bury him, along with the good he did.

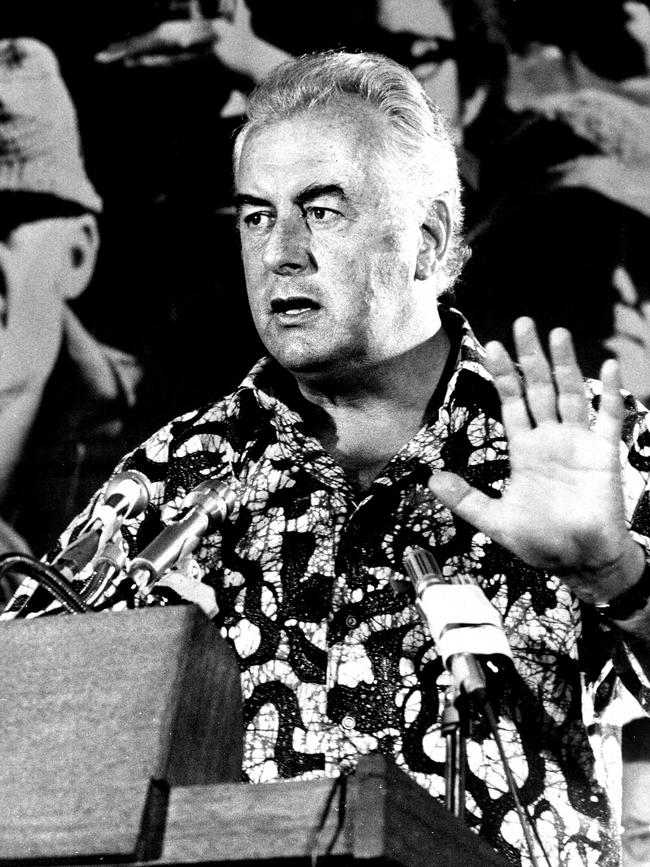

The real tradition for which Wong speaks is not Hawke’s. It is Gough Whitlam’s. It was Whitlam who initiated the first dramatic policy shift on Israel almost immediately after coming to power in 1972, reversing Australia’s previous bipartisan stance at the UN.

It was Whitlam, too, who told VP Suslov, a senior official in the Soviet foreign ministry, that he looked forward to the time when “the gradual increase in the size of the Arab population in Australia” would “balance” the “Jewish pressures” and their “crude blackmail” away. Yes, Whitlam repeatedly paid lip service to Israel’s right to exist. But in the name of being “neutral and even-handed”, the decisions he took showed an utter disregard for its survival.

Thus, in the Yom Kippur War, beginning 50 years and one day before the Hamas atrocities opened the current conflict, Whitlam refused to condemn the Arab nations that, like Hamas, initiated the conflict without warning. Israel’s “arrogance and intransigence”, he claimed, had brought the conflict on itself.

He then loudly condemned the US for providing weapons and ammunition to aid Israel’s self-defence, while neglecting to make even the mildest protest against the Soviet Union’s military assistance to invading Arab states.

Israel’s ability to turn the tide merely increased his sense of distaste: as scholar and commentator Frank Knopfelmacher acutely observed, the left liked Jews – so long as they never won.

The contrast with Hawke could not have been starker. Moved by a visceral identification with the cause of Jewish statehood, he was not afraid of confronting the left’s newly evident hostility to Israel.

In part, Hawke’s attitude reflected a deeply personal attachment to Israel itself. The qualities of Israelis he fell in love with from the first moment of arrival in Tel Aviv in 1971 – what he called the “cocky insouciance”, the egalitarian irreverence, the mixture of extreme informality (casual jeans, he said, were the national costume of choice) and relaxed attitudes with a readiness to leap into action at the first moment – were, as his biographer Blanche D’Alpuget observed, all attributes he himself embodied and prized.

Additionally, the story and reality of modern Israel were compelling. The Israel Labour Party had long dominated Israeli politics, and the trade union movement, the Histadrut, played a central role in shaping the country’s political and economic life.

For the leader of the ACTU, the industrial wing of the Australian labour movement, whose party had been in opposition for all but 11 of the previous 50 years, this could only deepen the country’s charms.

And Hawke immediately sympathised with a nation he believed “the world community had created and invested its conscience in” when the UN, under the presidency of ALP foreign minister HV Evatt, presided over the inauguration of the state of Israel in the aftermath of the Holocaust.

It is consequently unsurprising that Hawke was one of the first senior foreign leaders to visit Israel in the weeks immediately following the initial onslaught of the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and to tour the recently occupied war zones. And it is unsurprising, too, that he was outraged and appalled by Whitlam’s actions.

Showing no hesitation, he mercilessly assailed Whitlam and the parliamentary leadership of the ALP. Talk of “even-handedness” was, he said, a morally repugnant “abuse of language”. After all, the Arab states attacking Israel were not seeking some balanced reordering of territory and entitlement; their goal, obvious in deeds and often in words, was the destruction of Israel and its people.

Adopting that stance was hardly costless. The Friends of Palestine placed an open letter in the form of an advertisement in The Australian condemning “Mr Hawke (for) prostituting morality in the service of a fascist regime”.

Hawke and his family received death threats and required police guard. The security and surveillance at the Biennial Conference of the Zionist Federation of Australia and New Zealand, where Hawke delivered an oration on Australia Day in 1974, was prodigious. Speaking “as an individual Australian”, he said at that conference: “I know that I am not an island and I know that if we allow the bell to be tolled for Israel it will have tolled for me, for us all, and we have all to that extent … been diminished.”

The gulf between Hawke and Whitlam only widened after that. As historian Suzanne Rutland makes clear in her masterly and not sufficiently acknowledged research into this part of Australia’s history, the nadir of Whitlam’s career, and of his moral collapse, was not reached in the ignominious dismissal. Rather, it occurred in a much less known event during the election campaign that followed.

On December 10, 1975, just three days before the election, Whitlam clandestinely met two representatives of Saddam Hussein’s Baath Party.

After agreeable talk of the global threats posed by imperialism and Zionism, Whitlam described his dismissal as a coup d’etat and asked them for a secret donation of $1m to help cover election expenses. The “Jewish pressures” against the “democratic forces” in Australia were “enormous”, he said. They could be rebuffed only with the Arab states’ aid.

The conditions the Iraqis stipulated for the funds – conditions Whitlam apparently accepted – included being made privy to any “special information” about the Middle East that Whitlam received from the US and Israel, and “an assurance that Mr Hawke would not become leader of the Labor Party”. When reports of this meeting emerged early the following year Whitlam was severely reprimanded by the federal executive of the Labor Party.

Hawke, in contrast, only deepened his attachment to Jewish issues, increasing his contacts with the Zionist movement and with current and former Israeli officials. In 1979 he pursued the cause of Jewish “refuseniks” in the Soviet Union who were forbidden to migrate to Israel, travelling to Moscow as an unofficial envoy to present their case.

His devastation when Soviet leaders falsely assured him that the refuseniks would be allowed to leave, only to then renege, was shattering to an existential degree. That it was, as he later recounted, the only time in his life when he contemplated suicide highlights the concentrated passion of Hawke’s identification with the people and cause of Israel.

The man widely considered the most aggressively Australian figure in public life (the larrikin drinking binges, the carousing camaraderie, the pungently flattened vowels, the boisterous gregariousness and bar-room humour) was the same man who would tell close Jewish friends that “If I were to have my life again, I would want to be born a Jew”. Talking of Israeli affairs, he was known to declare “I’m an Israeli!” – reminiscent, in its own way, of president John F. Kennedy’s “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech in West Berlin in 1963.

Hawke succeeded to power as the ALP’s next prime minister in 1983 and reversed much of Whitlam’s foreign policy dictates. The retreat from Israel was over. It is true that, particularly after Likud Party founder Menachem Begin broke the Israel Labor Party’s stranglehold on power in 1977, Hawke criticised policies he considered counter-productive or inadvisable, but his foundational sympathy for the Zionist project of Israeli statehood never wavered.

Nor was he ever sympathetic to weasel-words counselling Israel to seek a two-state solution with terror groups and nation-states explicitly committed to the Jewish state’s annihilation. But the contrast between Whitlam and Hawke runs much deeper than that – and it is those deeper underpinnings that are the key to the difference between Hawke’s vision of the ALP and that embodied by Wong and Anthony Albanese.

A crucial component of Hawke’s admiration of Israel was his respect for the pride Israelis felt in their nation’s achievement – from making the desert bloom to the strongly held sense of “mamlakhtiyut”, or civic obligation. He admired that pride because he was himself unabashedly nationalistic, as the Australian labour movement had traditionally been.

Nothing makes that clearer than his 1983 election launch speech at the Sydney Opera House that addresses “my fellow Australians” and exalts “the true Australian way”. Nor can anyone who has read them readily forget the final line of acknowledgments in his memoirs, which declares his devotion to “this country, Australia, that I love, unashamedly, with a passionate intensity”.

Much has been made of this connection between ordinary Australians and Hawke, which for most of his career constituted mutual adoration. Whereas Whitlam’s natural arena was parliament, which he dominated, Hawke’s was television.

He used the new medium not simply to argue points but, in the words of Labor speechwriter Graham Freudenberg, “to communicate his whole personality”. Through it he effortlessly transmitted his distinctively Australian, everyman charisma into the homes of millions. “The simple fact is that I like people,” Hawke himself later explained. “Australians regarded me as one of them, and I felt part of them.”

And like most Australians in the 1970s and early ’80s, Hawke viewed Australia and its past as a story of pluck, courage and tenacity against prohibitive circumstances. Convict origins, distance’s tyranny and the challenges of internal geography had been the impediments to prosperity. The struggle to create a “workingman’s paradise” had the aura of the heroic about it. Whatever the nation’s flaws, its accomplishments were a measure of human progress.

Hawke’s view of Israel’s story mirrored that outlook. Here was a geographically isolated democracy, struggling to ensure decent lives for ordinary people, with the additional challenge of contending with a surrounding perimeter of nations sworn to wipe the nation off the map. “Plucky little Israel” and “plucky Australia” could have been cut from the same cloth, both born out of unpropitious circumstances, both making a go of it against the odds.

Hawke’s upbringing in the manse, the son of a Congregationalist minister, where he learnt early that “everyone, all humans, were kin”, meant that he could accommodate a nation such as Israel which, however secular its modern story, grew out of religiously inflected roots. The Christian universalism that underpinned Hawke’s secular patriotism allowed for a passionate and simultaneous commitment to both Israel and Australia.

It encouraged, too, the development of a core of principled conscience that enabled Hawke, for all his gregarious love of the crowd, the party, the movement and the people, to stand in opposition to the left’s political tide pushing against him on the Israel question.

In the end, however, the tide was running too heavily the other way. Whitlam’s real significance in that respect lay in his role as a harbinger of the future, rather than in what he attempted with his own poorly managed interventions.

Shifting the goal of Indigenous policy from integration to the ill-defined concept of self-determination; embracing multiculturalism, as if the culture Australians had forged since settlement was just one option among many; moving from the US alliance towards a “non-aligned” stance that was a thinly veiled neutralism; adopting a strident advocacy of pro-independence movements and endorsing their criticisms of Australia’s traditional allies; and placing an excessively high valuation on the UN – all these formed part of a package that took its distance from the West and from Australia’s Western heritage.

To that extent, Whitlam was a transitional figure. His assumptions about economics may have been cast in the past – Hawke considered him, so brilliant in other areas, “frightened by economics and finance” – but his view of the world was imbued with the spirit of the 1960s, including its turn from the celebration of Australia to a far darker vision.

In effect, the left’s image of this country’s history and its people gradually shifted from the parable of an indomitable nation forging its own luck to “settler colonialists” whose overriding characteristic was guilt.

The past was no longer the place where the workingman’s paradise was created in the face of enormous difficulties. Instead, it became a place where, in the words of Hawke’s prime ministerial successor, Paul Keating, “We took the traditional lands. We brought the diseases. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers.”

It wasn’t the Australians of 100 or 200 years ago who did these things — it was you and me: us. The defining feature of myth is that it brings the past directly into the present: here a new myth was being forged, in which there were vices and no virtues, faults and no triumphs.

By exactly the same mechanism, Israel’s image shifted. If we were “settler colonialists”, irremediably tainted by the original sin of settlement, Israel was surely even worse. The Israeli qualities Hawke had so greatly admired – the pride, the bluntness, the assertiveness – were accordingly morphed into mortal sins. And most grievous of all, Israelis showed no sign of self-flagellation, much less a cringing longing for forgiveness.

The consequences of that change in the attitude to Israel, which is dogma on the left, are not limited to our impact on world affairs.

In Whitlam’s day, foreign policy had few immediate domestic effects. His interventions didn’t provoke the anti-Semitic outbreaks that we witness now, where the worsening climate of public debate, the cancellation of any genuinely open debate on university campuses, the general extremisation of political discourse have helped ensure the domestic and the international are not just connected but merged.

Set in the context of that climate, the Albanese government’s obsessive focus on Israel – which, since October 7, 2023, has seen its most senior ministers devote at least five times as many words to implying Israel is breaching international law as to criticisms of any other foreign country or of Hamas – cannot but have fanned the flames of anti-Semitism. That it shirks its responsibility in that respect, when the realities are so glaringly obvious, is a devastating indictment of its calibre.

That is why Hawke matters more than ever. Seen against the backdrop of the current turmoil, the compelling feature, and enduring merit, of Hawke’s stance will always remain his willingness to stand for his values.

Hawke later described Keating saying to him, “Alright for you, and your Jewish mates in Israel. But I’ve got a whole lot of Muslims in my electorate and it doesn’t help me.” “Well, Paul,” Hawke replied, “I’m sorry about that, but that’s the way it is, mate.”

It is that principled attitude that this government – Whitlam without the grandeur – has turned its back on. To do so in the context of an oration devoted to Hawke merely compounds the tragedy. There is, in the end, such a thing as moral courage. And there is such a thing as its absence.

Henry Ergas is a columnist with The Australian. Alex McDermott is an independent historian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout