William Tyrrell: Evil is out there, too often much closer than we think

Police investigating the disappearance of William Tyrell had a long, long list of suspects. |EXCLUSIVE BOOK EXTRACT

There is a convicted sex offender living in a bush camp near the quiet street where your kids like to play. Do you have the right to know? Not currently.

What if there is more than one? What if there are, in fact, dozens or even hundreds of convicted sex offenders living in your neighbourhood, and what if police think that one of them may be responsible for the abduction of a small child in a Spider-Man suit, William Tyrrell? You still don’t have the right to know.

The Child Protection Register isn’t a public document. According to a report by the NSW Law Enforcement Conduct Commission, published in November last year, there are 4344 names on the list. That is an increase of 83 per cent in just 10 years.

The increase is due, in part, to children being believed more often. But the list is not in perfect shape. Police are supposed to be assisted in running the register by the courts and government departments.

In reality, police struggle to keep it up to date. Not everyone’s name gets passed on. Some names drop off when they shouldn’t.

Last year Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton announced his intention to open a national “child-sex register”, saying it would be the “toughest crackdown on pedophiles in Australia’s history”. Not everyone supports the idea. They fear a kind of vigilante justice, and that fear is probably valid.

App users tap here to listen to an extract of Missing William Tyrrell

Also, the idea that sex offenders are creepy old men seeking sexual favours by offering lollies to little kids isn’t accurate. The vast majority of sex offences are committed by someone already known to the victim (one recent study suggests 85 per cent of children who become victims of sexual assault know their offender.)

Still, even NSW police investigating William’s disappearance were appalled by how many sex offenders they would have to investigate.

They have since admitted that the Australian public would probably be “outraged” to know the extent to which sex offenders tend to congregate in certain areas.

Lawyers for the media tried during the recent trial of former NSW detective Gary Jubelin to have the figures for certain parts of NSW made public, arguing that there is “clear public interest” in knowing how prevalent child abuse is in certain areas.

The application was refused.

That said, we know that some — not all, but some — senior police investigating William’s disappearance very quickly formed the view that he may have been abducted by a local pedophile or pedophile ring.

A close study of the notes taken by police on the morning of William’s disappearance — September 12, 2014 — clearly show their concern. One of the first things that the first police officer on the scene, Senior Constable Christopher Rowley, who arrived just nine minutes after the triple-0 call, did was make sure the local Child Protection Register was checked.

Nobody who lived on Benaroon Drive in Kendall, where William had last been seen playing, was on it, but in the local area?

Police at one point had more than 600 names on their list. And so began the painstaking strategy known as “rounding up the usual suspects” — tracking down local men with a deviant interest in children who happened to be around that day.

Obviously this isn’t a hi-tech method but when it comes to policing, the old strategies are often the best. Take the case of Brisbane boy Daniel Morcombe, who disappeared from a bus stop in 2003. In “rounding up the usual suspects”, police happened upon local sex offender Brett Cowan, who admitted he had driven past the bus stop that day. It took police 13 years to get him for Daniel’s murder but get him they did.

In William’s case, police went knocking on the doors of old caravans parked deep in the forest, near where he’d been playing. They poked their heads into tents and humpies.

One of Tasmania’s pedophile priests, Derek Edward Nichols, who at the time of William’s disappearance was in his late 70s, used to live a short walk from William’s foster nana’s house in Kendall. He also used to sing in a local choir, having trained in both choir music and the pipe organ.

Nichols had been convicted of indecently assaulting a 12-year-old boy in Tasmania in 1987. Twenty years later he was also found guilty of possessing child pornography. He was one of the first suspects interviewed by detectives investigating the disappearance of William.

“I was living in Kendall and the police came to see me because I was on the Child Protection Register,” he said.

They searched his house and took a statement. No evidence could be found to link him to the crime, so detectives moved to the next name on the list.

Frank Abbott, aged 78, is serving time in a NSW prison for a string of assaults against young boys. He is another of the people rounded up as a possible suspect during the Tyrrell investigation.

Strike force detectives have twice ordered a search of the area where he used to live. They brought in cadaver dogs and an excavator and turned a woodpile into chips. Nothing related to William was found.

At the same time detectives from the sex crimes unit were examining child abuse material, much of which is these days found online. It’s not uncommon for pedophiles to communicate using little motifs, or symbols. It could be something innocent like a picture of a child on a man’s lap holding a pink rubber duck. The duck is the clue. To those who operate on the dark web, these symbols are used by men to alert each other to their preferences.

Strike force detectives were forced during the glummest days of the investigation to infiltrate pedophile networks. They went undercover.

Some had to watch thousands of child-abuse videos and view photographs hoping — dreading — that they might find William on the dark web, or else on a USB that had been passed to them in a carpark by somebody who trusted them to be of the same inclination.

They did it because finding William was the most important assignment of their lives, and also the hardest. Some broke down and some will never work again. None will ever look at the world in the same way.

They also looked closely at the list of people who turned up to search for William on the day he disappeared.

Why? Well, anyone who has volunteered at a bushfire — not fighting fires, necessarily, but working the coffee urn or even sorting through the many items that get donated — will know the protocol.

You turn up, ready to help, and they make you register.

There are several reasons: safety is the main one. It is also because the culprit — in the case of arson, the fire bug — will sometimes return to the scene of the crime to admire their handiwork.

It is the same with crime. The perpetrator will sometimes drive past the crime tape and the media pack (in the case of murder, they often return to the burial site).

One name stood out: the man in question was a member of the SES from Taree. He had arrived in a truck with other members of his crew about 4pm on the day of William’s disappearance. He had a job at a local service station, about 10 minutes from Benaroon Drive. He drove a small white van, and William’s foster mother had told police she had seen a small white station wagon parked in the street an hour or so before he disappeared.

He had been known to park his van near the Kendall tennis courts or the Kendall showgrounds between his shifts at the local service station, to sleep in it overnight. And he was a registered sex offender.

Detectives wondered: could this be a lead?

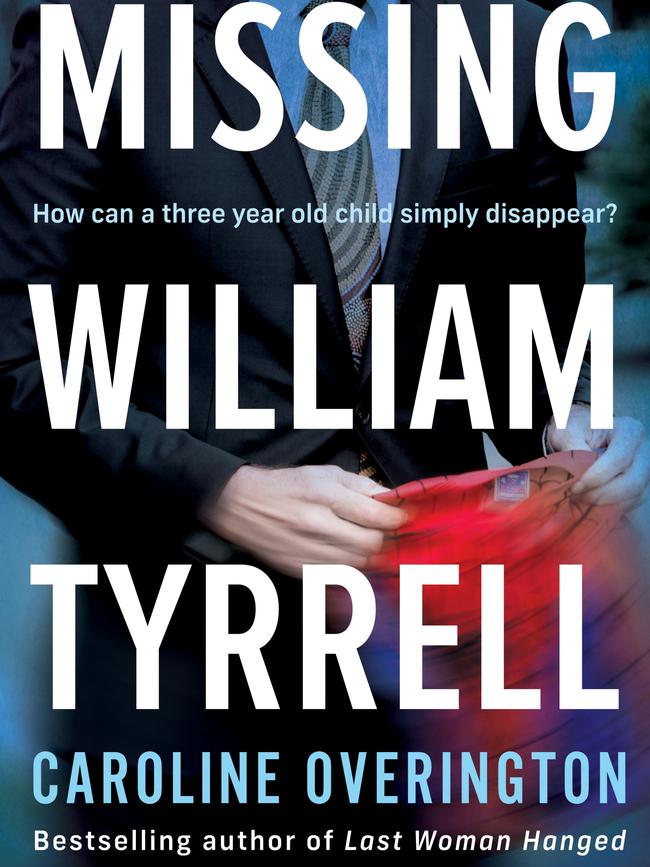

This is an edited extract from Finding William Tyrrell by Caroline Overington (HarperCollins), out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout