Why Xi may well regret Beijing’s alliance with Putin

If an ‘unthinkable’ war can occur in Europe driven by one man’s delusions of grandeur, what is the likelihood of another’s igniting an even more destructive conflict in Asia?

But the repercussions for Australia’s Asian neighbourhood may be even more far-reaching depending on the answers to three questions. Will China risk international opprobrium and the wrath of the US by supporting Russia economically and militarily? Does Putin’s invasion of Ukraine make it more, or less, likely that China’s Xi Jinping will emulate him and take Taiwan? And how will Asian countries respond to the trampling of Ukraine’s sovereignty by a wannabe great power?

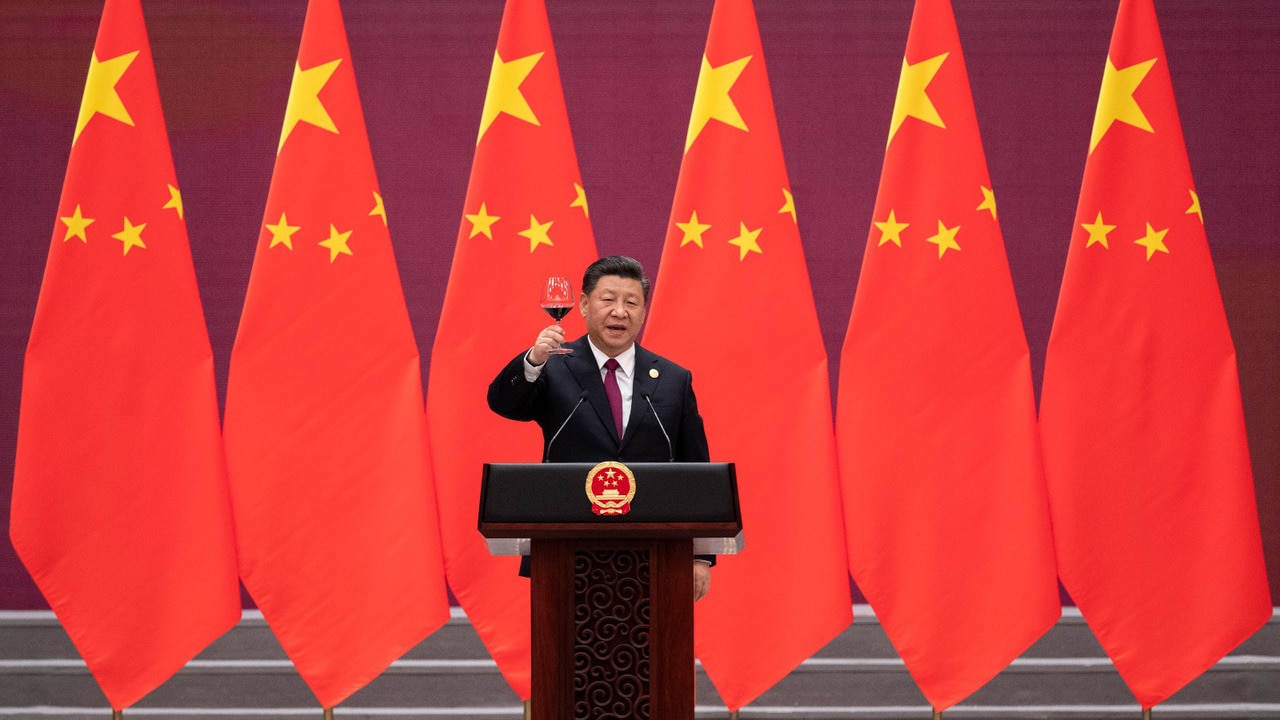

Alarm bells have been ringing in Washington since US intelligence assessed that Beijing might be readying to supply Moscow with much needed arms and supplies – the kind of spoiling action the US most feared following the watershed Sino-Russian Joint Declaration of February 4. This bound together the two revisionist states in a “no limits” strategic partnership aimed at replacing the Western-led international order with one more conducive to the interests of China and Russia.

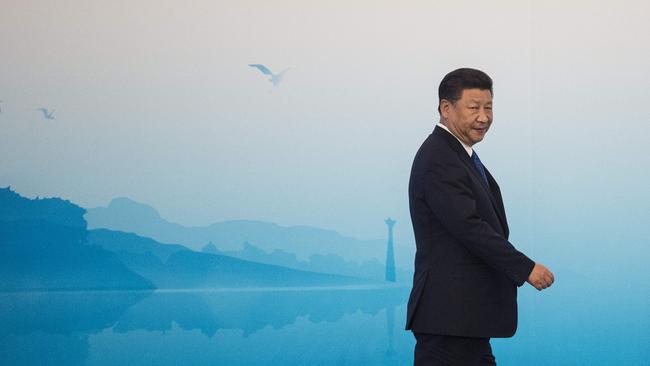

On the face of it, the bromance between Putin and Xi is indeed a worrying development given the size of their countries and populations. Their strategic geography has allowed them to dominate the Eurasian landmass historically. “Who dominates Eurasia dominates the world,” American geopolitical theorist Nicholas Spykman famously declared last century.

Both China and Russia are also nuclear powers with large militaries and a willingness to use them. They increasingly co-ordinate their diplomacy in the UN and influential multilateral organisations. China’s refusal to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and join international sanctions underscores Beijing’s capacity to frustrate Western diplomacy and international policy.

Western pessimists conclude that Xi will be the main beneficiary of Russia’s determination to challenge Europe’s security order by distracting the US, forcing the Biden administration to divert resources and troops away from Asia to Europe and weakening the ability of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue to push back against China in the Indo-Pacific. New Delhi’s reluctance to criticise Russia for its invasion of Ukraine threatens to drive a wedge between India and its Quad partners, the US, Japan and Australia.

This gloomy prognosis needs a reality check. The Sino-Russian super bloc is overhyped. Pessimists ignore the many limits to the supposedly no limits friendship.

China is beginning to suffer “a bit of buyer’s remorse regarding its new quasi alliance”, Centre for a New American Security chief executive Richard Fontaine writes in The Wall Street Journal.

Putin’s war of conquest leaves “Beijing badly exposed”. Chinese companies trading with Russia worry about being sanctioned by Washington and having to choose between access to the US market and Russia’s. “Powerful countries representing half of the world’s economic output oppose Moscow’s aggression, while China has aligned itself with a reckless Russia that faces long-term isolation and impoverishment even as its military flounders in the field,” Fontaine says. “The prospect has led many in Asia to rethink the region’s security.”

China is not known for sentimentalism. Internal policy debates suggest the risk of US sanctions, increased Western hostility and the hit to its international reputation is forcing a reassessment of relations with Russia. Putin’s adventurism has put Xi in the uncomfortable position of having to defend a pariah state that has blatantly transgressed the guiding principle of Chinese foreign policy – respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all states.

Xi, like Putin, expected Ukraine to collapse quickly, leaving the detritus to be cleaned up well in time for Xi’s coronation at the National People’s Congress later this year. However, instead of the geopolitical stability and post-Covid economic recovery he anticipated, Xi’s bid for a third term as China’s undisputed leader faces unexpected headwinds.

Veteran China analyst Minxin Pei warns that “whether China wants it or not, its future is now tied to Putin’s fate”. That future is decidedly less rosy than it was a month ago. Already under strain from its unsustainable zero tolerance approach to Covid, the disruption to global trade and supply chains from the Ukraine crisis and Western sanctions could push annual growth below 5 per cent. “Instead of being a net beneficiary of a conflict between the West and Russia, China now finds itself perilously close to being collateral damage,” says Pei.

Asia’s rising power may not surpass the US economically and technologically as Xi so confidently assumes. With a demographic bomb ticking as the country ages rapidly, time may no longer be on China’s side. It’s in danger of losing both European and US market share as Western anger grows over Xi’s support for Putin – anger that could become incendiary if Xi decides to provide arms and sanctions relief to Putin.

Even before the invasion, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg described the two authoritarian powers “as operating together”.

To make matters worse, Beijing’s much-hyped but languishing Belt and Road Initiative has been seriously disrupted by the loss of a major transport corridor from China to Europe that runs through Ukraine and Belarus.

China can’t increase imports of Russian energy rapidly to compensate for the loss of Moscow’s European and American markets. Additional oil and gas pipelines across the vastness of Siberia would take decades to build at great cost. Ships to carry oil and gas are in short supply. Sino-Russian trade, which topped $US146bn ($195.3bn) last year, is still dwarfed by both countries’ trade with the West.

For China, the loss of access to Western markets and capital in exchange for greater integration of the Russian and Chinese economies is a losing proposition. The same goes for Russia. The EU is Russia’s largest investor and takes more than 37 per cent of its exports. Lose much of that and Russia risks becoming a Chinese vassal state – not the future Putin envisaged when he started his war.

Analysts are divided over what Ukraine means for Taiwan. Some believe Putin’s adventurism will encourage Xi to speed up his plans to invade and occupy Taiwan using the same historical, cultural and ethno-linguistic justifications. Beijing’s propaganda line would be that, unlike Ukraine, Taiwan is not a sovereign state but an integral part of China.

But in preventing a speedy, clear-cut Russian victory the Ukrainians have done Taiwan a favour by making Xi think twice about the wisdom of an early invasion of the island he covets.

Their preparedness to fight and, if necessary, die for their freedom has inspired the Taiwanese while bringing home the full horrors of what an invasion by the People’s Liberation Army would mean for them. There won’t be any safe places for Taiwanese refugees and displaced people. This realisation has spurred Taipei to bolster the island’s defences and ensure adequate supplies of food, fuel and weapons are in place before an invasion materialises.

Much will depend on how firmly the US and its allies push back against Putin and how successful the Russian dictator is in bringing Ukraine to heel and resisting Western sanctions. Despite reluctance to commit NATO forces to the fight, an alliance that recently was declared as “brain dead” by French President Emmanuel Macron has shown a previously unseen degree of unity and resolve to confront Putin.

Xi will have taken note of the US and European response as well as the overwhelming vote in the UN to condemn the invasion by 141 of its 193 member states. Invasions are the recurring nightmare of every small and medium nation and still a big no-no, even in a fraying international system.

Political momentum is building in the US to ramp up support for Taiwan and absorb important lessons from Ukraine: be prepared; take the threats of dictators seriously; fight asymmetrically; mobilise coalitions of the willing; win the information war; leverage the West’s economic and financial strengths; fully commit to the fight; and bluntly spell out the consequences to China of invading Taiwan.

Of course, China will be far more difficult to sanction than Russia. It’s the world’s manufacturing hub and second largest economy. And the reciprocal costs will be higher. Sanctions can be a two-edged sword. Witness Europe’s reluctance to embargo Russian oil and gas for fear of damaging its own growth.

Still, the prospect of severe, punitive sanctions will give Xi cause to pause. Although 12 times larger than Russia’s, China’s economy is also more exposed and dependent on trade and investment from the West to sustain the growth that legitimises Communist Party rule.

The world has been given a salutary lesson in the might of the US dollar, America’s convening power and the capacity of sanctions to wreak havoc on a targeted country. Beijing will redouble its efforts to curtail the dollar’s privileged position at the apex of the international financial system, but it won’t be easy to do so.

The last thing Xi needs is to be cut off from the SWIFT international payments system and for decoupling with the US to accelerate and expand to include a hostile Europe, a double economic whammy that would cost China dearly in the long run.

An alienated EU would jeopardise billions of dollars in trade and investment along with decades of political capital invested in building strong ties with the world’s third largest economy.

China is particularly vulnerable to energy disruptions. Increased imports of Russian oil and gas won’t future-proof China from threats to the vital ship-borne supplies of energy that transit the easily blockaded Malacca Strait.

The Ukraine crisis is also causing a security rethink in Asia and a hardening of attitudes towards China among close US allies, not just Australia. Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which has been inching towards a tougher line on China, is on the threshold of a historic shift in sentiment that could shatter long-held taboos. Chief among them are Japan’s self-imposed restraints on defence spending, the use of its military and acquiring nuclear weapons.

Former prime minister Shinzo Abe, who remains influential in the LDP, wants Japan to consider hosting American nuclear weapons that could be loaded on to Japanese fighter aircraft should the country face an existential threat. Although Abe’s call has been rejected by Defence Minister Nobuo Kishi, many senior LDP figures believe Japan’s entrenched pacifism must give way to a more hard-headed approach to security. A particular concern is Russia’s decision to target Ukraine’s Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plants, an unsettling development for a country that operates nuclear power plants of its own.

Uppermost in their minds are two questions that will be debated intensively in coming months. Would Russia have invaded Ukraine had Kyiv retained its nuclear weapons from the Soviet era? Can Japan rely on the US for protection in the event of a conflict over Taiwan or disputed islands in the East China Sea?

In South Korea, a newly elected conservative president has committed to making a “deeper alliance” with the US a central plank of his country’s foreign policy. Yoon Suk-yeol has signalled a desire to work more closely with Japan and Australia on security. This provides a pathway for South Korea to join an expanded Quad. An Asia-focused quinquepartite partnership of democracies would make it much more difficult for Xi to realise his dream of regional dominance.

Southeast Asia is another matter. Aside from Singapore, no other member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations has condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or imposed sanctions. In fact, sanctions were explicitly rejected by Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo. The bloc’s response to the crisis was aptly described as “a masterclass in passive avoidance and self-interest” by this newspaper’s Southeast Asia correspondent, Amanda Hodge.

ASEAN is no longer in the driving seat of regional affairs, a cherished position that has not survived China’s return as an ambitious great power. This means Southeast Asia has less weight in the global and regional security debates that matter. Even so, the contest with China for the hearts and minds of ASEAN’s 680 million people is likely to remain an Australian foreign policy priority.

There are four other important takeaways for Australia. First, the Ukraine crisis has moved allies towards the Morrison government’s view that a more robust defence of a “free, open and inclusive international order” is needed. These are almost the exact words of South Korea’s new leader. Once reticent Europeans are coming to the same conclusion.

Second, Australia is no longer an outlier in pushing back against the aggressive behaviour of totalitarian states. The early determination of the Turnbull and Morrison governments to resist China’s coercion and bullying helped fortify Ukraine in its defensive war against Russia and is an exemplar for other threatened nations.

Third, aligning more tightly with the US does not preclude a more agile, distributed and expansive foreign policy. Our diplomatic dance card is filling up as other countries seek our counsel, support and resources.

Finally, the many sceptics who dismissed the idea that the world was entering a new cold war that could easily develop into a hot war should ponder this question. If an “unthinkable” war can occur in Europe driven by one man’s delusions of grandeur, what is the likelihood of another’s igniting an even more destructive conflict in Asia?

Alan Dupont is chief executive of geopolitical risk consultancy the Cognoscenti Group and a non-resident fellow at the Lowy Institute.

Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is a seismic geopolitical event. It’s shaping to be more destabilising and consequential than anything the world has seen this century, overshadowing Covid, the global financial crisis and the rise of al-Qa’ida. It has shattered Europe’s long peace; raised the spectre of a nuclear confrontation between NATO and Russia; widened the divide between the West and Eurasia’s autocratic states; and almost certainly ended Russia’s quest to be a Eurasian great power.